Principles of Soil Fertility

Improving soil fertility was a fundamental value for the pioneers of organic farming, but the conservation of fertile soils has often been insufficiently considered. Organic farming depends heavily on the good natural fertility of soils. Weakened and damaged soils can no longer provide the services expected of them. Their fertility must be carefully maintained. This brochure presents soil fertility from several angles, without claiming to provide a universal manual. Rather, this information should encourage a continuous rethinking of our relationship with the soil and its (re)construction to ensure the sustainability of our food supply.

Why revisit the question of soil fertility?

Organic farming lives from and with soil fertility – we are the Children of the Earth. Soil is an ecologically vital asset that continuously renews its productive capacity. If we do not sufficiently consider its needs, it suffers: it loses vitality, becomes more sensitive to weather conditions and erosion – and provides less abundant harvests. In organic farming, soil fertility problems can hardly ever be solved purely technically. That is why exhausted or diseased soils need remediation through ecologically sound measures that help them regenerate. Despite all the problems and constraints, there are many intervention possibilities that allow us to honor our farming responsibility towards living soil. It is worthwhile, and not only economically.

The scientist Ernst Klapp defined soil fertility in the 1960s from his practical experience as "the natural and sustainable capacity of a soil to ensure plant production." It is therefore the soil's ability to provide plants with what they need for growth without relying on inputs and to deliver stable yields. Since then, agronomy has dissected the overall notion of soil fertility into a multitude of physical, chemical, and biological parameters. Making such detailed knowledge usable is now part of scientists' tasks. Many practitioners have developed their own strategies and techniques to conserve soil fertility. They learned by observing and trusted their intuitions. This knowledge complements that obtained through scientific trials and observations well. This brochure aims to encourage farmers to cultivate the soil in a truly sustainable way to maintain or restore its fertility and vitality based on proven principles and by experimenting with new possibilities.

Principles of soil fertility

The pioneers' soil

Organic farming developed as a modern agricultural method since the early 20th century, but its historical roots are as old as agriculture itself. For several decades, organic farming was practiced and developed only by a few connected farms. It gained more recognition and attracted more farmers in the 1980s and 1990s. Before presenting the current state of knowledge – scientific and practical – on good fertility management of soil considering holistic aspects, we recall its roots with some quotes from our "great-great-grandparents."

Impulses from soil biology

The landowner Albrecht THAER recognized in 1821 that "Humus is both a product of life and the condition for its maintenance." While most researchers focused on agricultural chemistry, Charles DARWIN discovered in 1882 something decisive for organic farming: "The plough is one of humanity's oldest and most valuable inventions, but the soil was regularly tilled by earthworms long before its invention." The new microscopes available since the early 20th century revealed the unimaginable diversity of life in the soil, triggering ecological reflection. Richard BLOECK could then write in 1927: "Cultivated soil has become a true living being under the action of soil microfauna and microflora." The notion of cycle' resurfaced, and Alois STÖCKL wrote in 1946: "… the persistence and improvement of soil fertility [is] only possible if there is a cycle of substances," but "there is hesitation everywhere to attribute crucial importance in this context to the small living beings of the soil." The co-founder of organic farming Hans-Peter RUSCH perceived in 1955 the essentiality of the life cycle: The "living substance" is "returned to every living being in the substance cycle for reuse." And agronomist SEKERA emphasized in 1951: "We understand fertility as the biogenesis of crumb structure by soil microorganisms."

Ideas and ideological motivations

Rudolf STEINER taught in 1923 during his Farmers' Course: "One must know that fertilization must revitalize the earth. … And seeds give us a representation of the universe." In England, Lady Eve BALFOUR said in 1943 that only ecology, linked to Christian values, could help us recognize that "everything in the sky and on earth is only parts of a whole." And her agronomist colleague Sir Albert HOWARD observed in 1948: "Mother Earth has never tried to farm without livestock – she always practices mixed crops." Organic farming must therefore take natural agronomy of Mother Earth as a model. Mina HOFSTETTER, one of the Swiss pioneers of organic farming, saw in 1941 the feminine qualities of the earth as key to a profound understanding of soil fertility. Mother Earth can address the farmer woman when she dedicates herself quietly: "… either she will continue to teach us or she will eliminate us."

Why do we speak of "organic" agriculture?

The "bio-logy" of organic farming was literally understood by its founders as a doctrine of life, a global philosophy of life and agriculture. Less attention was paid to different chemical substances and more to biocenoses formed by living beings or ecosystems, themselves considered as units forming an organism. Organic farming thus speaks of soil as an organism, of agricultural organism (the farm), terrestrial organism (the earth), and of organic agriculture, as well as the ecosystem formed by soil, farm, and "planet earth." The permanent interactions and persistence of natural and social life, which no technology can ever replace and which many pioneers consider in relation to spiritual and divine actions, were considered essential. The famous principle "Healthy soil – healthy plants – healthy people", formulated to show that everything depends on everything, has lost none of its importance for today's world.

A constantly evolving notion

At its birth, applied agronomy first considered soil yield as an essential measure of its fertility. Soil nutrient contents (mainly nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium) were taken as fertility indicators – chemical fertilizers were then generally considered inexhaustible and capable of replacing natural soil fertility. The growing evidence of resource finiteness, however, redirects the discussion on this notion in another direction. Essential for crop yields, the efficiency of nutrient transformations – also and especially in the general cycle – comes back to the forefront as a measure of soil fertility.

Soil fertility is both an ecological and biological process

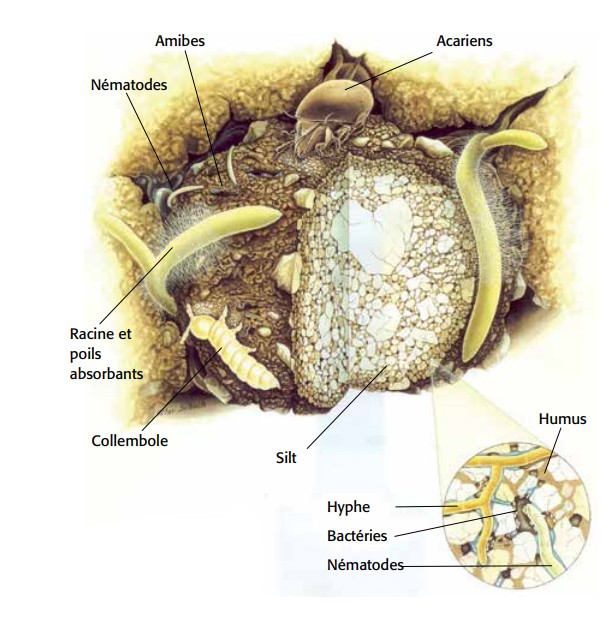

Soil is inhabited by an immense diversity of microorganisms, animals, and plant roots. A fertile soil can provide healthy harvests for generations needing little fertilizer, pesticides, and energy. In healthy soil, the living beings inhabiting it efficiently transform fertilizers into impressive yields, produce humus, protect plants against diseases, and make the soil crumbly. Such soil is easy to work, absorbs rainwater well, and effectively resists crusting and erosion. The filtering efficiency of soils is precious for groundwater quality and for neutralizing acids that rain extracts from polluted air and deposits on the soil surface. Fertile soils can also quickly degrade pollutants such as pesticides. Finally, fertile soils efficiently store nutrients and CO2, thus preventing eutrophication of rivers, lakes, and seas while contributing to reducing global warming. In the spirit of organic farming, soil fertility is therefore mainly the result of biological processes and not the presence of chemical elements. Fertile soils actively exchange with plants and are capable of structuring and regenerating themselves.

Between esteem for soil functions and the demand that it "works"

Today, one sometimes speaks of "soil quality" instead of soil fertility. However, soil quality is the sum of soil functions appreciated by society. This perspective can help broaden the view on soil to notions previously neglected. However, one must be aware that the definition of soil quality by determining its functions always depends on current economic and/or political constraints. The main natural functions of soil are:

- Production function: high-quality yields adapted to the site;

- Transformation function: efficient transformation of nutrients into yield;

- Habitat function: living space for an active and diverse flora and fauna;

- Decomposition function: decomposing and transforming plant and animal residues without hindrance to close the nutrient cycle;

- Self-regulation function: not to be or not sustainably be thrown out of a healthy balance. For example, by efficiently "digesting" pathogenic organisms present in the soil or suppressing those that arrive;

- Filter, buffer, and storage function: retain and degrade pollutants. Store nutrients and CO2 in the soil.

Scientific analysis of soil fertility

In contrast to the purely chemical approach to nutrients, soil fertility was long sought to be distinguished by humus chemistry by trying to define and classify humus through its different chemical structures. This brought little, and today other characteristics are examined such as nutrient availability, the C/N ratio of organic matter, as well as transformation processes at work in the soil and the quality of the humus it contains, which serve as measures for:

- the amounts of nutrients directly available to plants – Which elements are found in a hot water extract of the soil?

- the easily accessible nutrients found in the life cycle – What is the amount of microbial biomass and its C/N ratio?

- humus stability: stable humus is heavier than young humus – What is the complexity of its molecules? What is its density?

What does organic farming mean by soil fertility?

By "soil fertility," organic farming primarily means a property of living soil. Since soil fertility is a characteristic of soil as an organism that is never fully visible, we can neither grasp it intellectually in its entirety nor fully define it by analytical measurements – as with humans themselves. That is why the soil fertility we speak of represents a comprehensive perception of the soil, its influences on plants, and the analysis and measurement of some of its characteristics. The diagnostics and measurements presented in this brochure refer to the possibilities of observing the soil and describing it using its different characteristics:

- Physical characteristics can be identified, for example, using the spade test. Soils in good physical condition offer plant roots and all soil fauna living and working space and enough air to breathe. The farmer's task is to stabilize soil structure with plant roots, make it load-bearing, and avoid compaction by using different machines with great care.

- Chemical properties are identifiable by measuring various nutrients and possibly some pollutants and, for example, pH (acidity measure). The chemically well-endowed soil-plant organism has all chemical elements and organic molecules for its nutrition. The complex metabolic products of different organisms promote plants' immune reactions. By returning the extracted elements, we try to support the good balance of these properties. Overexploited soils must first be rebalanced.

- Biological properties of the soil are revealed by transformation processes occurring there as well as by the presence and visible traces of living beings found there. In ecologically balanced self-regulating soils, biocenoses are robust and active at the right time, and all animals, plants, and microorganisms act for each other. Our duty as farmers is to understand soil ecology well enough to create or recreate conditions for a robust balance. The overall effect of all these activities allows fertile cultivated soil to always provide good yields again. If this is not the case, we must carefully observe the above-mentioned properties to see if something is amiss.

The invaluable contribution of soil organisms

Fertile soils harbor a rich diversity of organisms all participating in important processes. Earthworms and insect larvae burrow and turn over the topsoil layers in their quest for dead organic matter. Their galleries aerate the earth, and the pores and galleries can absorb water like a sponge. Springtails, mites, and millipedes decompose litter, microorganisms transform animal and plant remains into humus, and finally bacteria decompose organic residues into their chemical components while predatory mites, chilopods, beetles, fungi, and bacteria control populations of organisms that could become harmful.

Earthworms are the architects of fertile soils

Bacteria and fungi – underestimated helpers

A single gram of soil contains hundreds of millions of bacteria and hundreds of meters of fungal filaments. Microorganisms (including those in animals' digestive tracts) can decompose plant and animal organic matter into its basic mineral components. Not only do they regulate nutrient cycles by decomposing organic matter, but some can also fix atmospheric nitrogen and form symbioses with plants. Bacteria and fungi are involved in almost all mineralization processes occurring in the soil. Mycorrhizal fungi (root fungi) infect plant roots to form symbioses. These open access for plants to a much larger volume of soil than they could have alone. Mycorrhizal fungi are also attributed positive influences on soil structure, and they also enable substance exchanges between plants they connect. Soil tillage disrupts the mycelial filament network in the soil, but a new one reforms afterward.

Taking Advantage of the Potential Offered by Gentle Soil Tillage

The general degradation of soil began millennia ago with the cultivation of land and intensive soil tillage, often linked to overgrazing by animals. The discovery of steel and the invention of the modern reversible plow intensified this process by causing intensive mixing of soil layers. The advent of tractors then allowed plowing at depths previously unthinkable. Erosion caused by intensive soil use has led to the loss of about 30 percent of arable land worldwide over the past 40 years.

The credo of organic farming pioneers was to loosen the soil deeply but to plow only superficially to preserve the natural soil stratification. Reduced tillage efforts are therefore very old in organic farming, and the practical implementation of gentle soil use in organic farming early on sparked many technical innovations, including for example the Kemink system (soil loosening and permanent traffic lanes), the claw plow, and the subsoiler with wings (the soil is superficially tilled while being loosened deeply). However, systematic research on reduced tillage in organic farming only began about 20 years ago.

Trials conducted under organic conditions have shown that reduced tillage allows increasing the humus content of the topsoil, promoting biological activity and soil structure, and improving its water retention capacity available to plants, which is an important yield factor especially during dry periods. The biggest challenges remain weeds, especially grasses and perennial weeds, as well as the breaking up of grasslands without deep plowing.

The need to treat the soil with even more care has stimulated practitioners and researchers to seek new solutions to the problems posed by reduced tillage. The use of ridge plows alone already helps to avoid subsoil compaction. New stubble cultivators allow very superficial soil work. Various machines that do not invert the soil, such as the chisel Écodyn, combine for example stubble shares that work the entire soil surface with widely spaced loosening tines mounted far apart. Direct seeding directly after green manure has even been achieved. Electronics also give hope for interesting innovations in weed control.

Climate change also contributes to restoring importance to systems aimed at increasing soil humus content. These innovations give organic farming a chance to combat global warming by sequestering carbon in the soil while improving productivity in arable crops through better exploitation of biological processes.

Knowing How to Assess Soil Fertility

Direct Observations

Are there simple methods to assess soil fertility? Yes, there are some methods that provide valuable information about soil condition today as in the past. However, it is also—and above all—a matter of taking the time to observe plants, the soil surface, the soil, and its inhabitants more closely.

Observing the Plants

The cultivated plant is the most important indicator plant. If it grows well and is healthy, the result will be a satisfactory and high-quality yield. If this result is achieved without excessive nitrogen fertilization or chemical/synthetic plant protection products, one can count on high soil fertility. The intensity of soil fertility is even more evident when the year's weather conditions are unfavorable (provided, of course, that the cultivated plants are adapted to the site). Weeds such as thistle or chamomile reveal deficiencies or problems such as compaction for example.

Interpreting the Soil Surface

The soil surface alone already provides information about the condition of the earth beneath. The presence of a protective plant cover allows the formation of a superficial crumb structure, which could be called the biogenesis of soil crumb structure. This is recognized by its round crumbs—or aggregates—that also prevent excessive surface crusting and soil erosion. Crusting and erosion phenomena can therefore reveal that soils are in poor condition. Increasing humus content reduces crusting and erosion.

Considering Soil Life

The activity of earthworms and small animals like springtails is recognizable by exit holes present on the soil surface. They are especially visible in spring when organic matter is available on the soil surface for soil organisms to ingest. One can then see many small worm holes and some larger ones. Digging with a spade allows seeing galleries pierced in the topsoil layer, and casts left by earthworms on the soil surface also reveal the intensity of activity of these soil workers.

The rate of decomposition of plant residues is also an indirect indicator of soil fertility. The simplest is to observe straw decomposition: if straw remains intact on the soil surface throughout the growing season, it is a sign that soil life is not very active.

Smelling the Soil

Fertile soils smell good; their odor is not unpleasant. For comparison, one can smell forest soil or soil at the edge of a field. If the soil smells of rot, something is wrong. Roots also have their own smell, coming from substances (exudates) they secrete. The roots of legumes and couch grass have a pleasant smell, and earthworms are often found nearby.

Some Tools to Refine Observations

The Spade Test

The spade test is a hands-on method that has proven effective for assessing soil structure. The spade test allows seeing before soil work what the depth of the topsoil layer is. If plants grow more slowly in dry years, the culprit is often blamed on the weather. But could it also be that roots cannot penetrate deeply enough due to a disturbed layer? During summer months, observing cultivated plants also allows assessing soil condition after sowing and the influence of soil work. Sampling is done in four steps and requires a flat spade and a small hand fork (to clear roots).

- Step 1: Start by choosing a representative spot of vegetation and soil surface for the test. Always perform 2 or 3 tests.

- Step 2: The spade cut should be made so as to include at least one plant of the crop. To easily remove the soil block with the spade, first dig a trench along one long side of the soil block as long as the spade blade.

- Step 3: The short sides of the soil block are cleared with a series of spade cuts.

- Step 4: The soil block can now be removed by carefully tilting the spade backward. Placing the spade and its sample on a hip-height support facilitates further evaluation.

- Important: Take photos and notes before and during each spade test; this helps better assess and document the evolution of the soils examined.

The spade test should include the following points:

An Example of a Spade Test

The spade test example above was conducted in 2010 in a winter spelt field. This farm has been cultivating its soils for years without plowing. The soil surface is not distinguishable, but the crumb structure of the upper part indicates it was in good condition at that time. The horizons are very easy to identify. The limit of soil work is roughly at the middle of the soil block. One can also see how deep the soil was worked before sowing spelt: about 15 cm deep. The soil structure of the topsoil (A horizon) is very good. One can distinguish small rounded aggregates and the spelt roots can well colonize this part of the soil as evidenced by their abundance and the presence of many rootlets. The soil also crumbles easily, indicating its condition is good to very good. The closer to the limit of the unworked subsoil, the larger and more angular the aggregates are. Roots are visible and extend beyond the bottom of the soil block. Spelt roots can still colonize this soil. This soil is firm; this can be interpreted as its natural load-bearing capacity in a no-till system. The condition of this soil can be described as satisfactory to good. The boundary between worked and unworked soil is clearly visible. What is decisive here is that roots continue to grow regularly and rainwater does not stagnate (earthworm galleries). Harmful compactions and naturally dense deep layers often cannot be distinguished without considering the soil working technique—especially if roots can still colonize the soil. Penetrometer evaluation may not suffice in this case. The evaluation should also consider the position of spelt in the crop rotation. The result would be judged less good if it were the first crop after a temporary grassland of grasses and legumes, but the impression left by this spade test is good for a second or third crop (with catch or relay crops).

The Penetrometer

The penetrometer is an iron rod equipped with a pressure spring and a pressure indicator. This probe measures the penetration resistance offered by the soil, generally its density. The probe rod is pushed into the soil applying constant pressure. If soil resistance increases, it means a compaction (or a stone) is present at that depth. The depth can be read on the probe or measured with a tape. The measurement should be repeated several times. However, this probe does not provide precise information about the internal condition of the soil: digging is necessary if problems are suspected.

The pH Meter

Soil pH (the "acid-base status" of the soil) affects nutrient availability for plants and strongly influences soil life. The Hellige pH meter provides reliable pH measurements. Measurements should not be made only at the soil surface. It is advisable to know the pH at 10 and 20 cm depths as well, as it can vary significantly between soil layers. Fertilizer inputs, rock powders, and liming influence pH.

Maintaining and Improving Soil Fertility

Humus Management

Organic farming considers that humification can greatly help solve most pedological problems. There are good reasons for this since, on closer inspection, humus proves to be the pivot and central point of soil fertility:

- Humus readily deposits on the surface of aggregates forming a coating. Large clods preferentially break along these surfaces (points and lines of rupture), so that small aggregates remain intact. Humic coatings impregnate aggregates and protect them against excess water: they disintegrate less quickly when it rains, so soils are less prone to crusting.

- These humus-rich surfaces prevent aggregates of heavy soils from sticking too strongly to each other, allowing them to be worked even in severe water shortage. Not only does humus lighten heavy soils, but it also improves the cohesion of light soils by "cementing" their aggregates!

- In crumbly and non-crusting soils, the amount of fine material leached to deeper soil layers decreases and rainwater infiltrates more rapidly, reducing erosion. These soils allow plant roots to penetrate deeper to find water during dry periods. These soils therefore have a better water regime.

- More humus also means more food for bacteria, fungi, and other soil organisms. More active soil microorganisms also suppress populations of pathogens present in the soil.

- In soil, green parts of plants decompose quickly into nutritive humus that feeds soil organisms. Lignified plant parts and dead microorganisms decompose more slowly. They bind with clay minerals to form what is called the clay-humus complex, or stable humus.

- Whether soils are rich or poor in humus also strongly depends on local conditions. Heavy and moist soils tend to be richer in humus than dry sandy or loess soils. Usually, the consequences of humus degradation caused by unsustainable crop rotations only become visible after many years. It is therefore normal that humus restoration through rotation also takes years. Inputs of composts from plant waste or manure help accelerate the process and partially compensate for humus deficits in certain rotations. But beware, good quality manures and composts also have their cost.

- An increase in humus content makes soils more crumbly and active and increases nitrogen availability. A decrease in humus content makes soils stickier, more prone to slaking, more susceptible to compaction, and decreases nitrogen availability.

How Can Soil Humus Content Be Increased?

- Composts of plant waste and manures provide the soil with more stable humus molecules that resist decomposition well and contribute to increasing humus content.

- Lignified crop residues decompose slowly and mainly favor fungi that decompose lignin and grow slowly, diversifying soil microflora. Such crop residues contribute to the formation of stable humus.

- Perennial grass and legume pastures included in crop rotations increase humus formation and provide the soil with a large, easily degradable root mass. They primarily supply nutrients for earthworms and microorganisms.

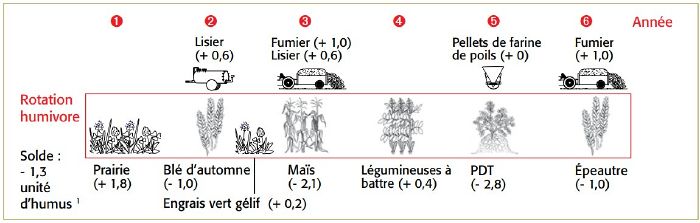

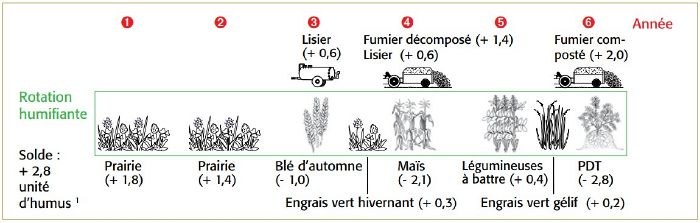

The Humus Balance

The goal of any agriculture should be to achieve on each plot at least a balanced humus balance over the entire crop rotation. The humus balance allows checking whether this goal is met or not. Methods for establishing humus balances generally rely on estimates and calculations based on crop rotations and cultivation techniques. Only a few methods, such as REPRO/Hülsbergen or Standort/Kolbe, allow valid calculation of humus balances for organic farms. They use national standards. Humus balances of different farms should be compared with caution. It is also recommended to regularly perform humus analyses that measure not only total humus quantity but also the quality of stable humus and the transformation of nutritive humus.

Crop rotations that preserve humus

In organic farming as well, following only market demands leads to not respecting certain crop rotation rules for short-term reasons: rotations become narrower and less balanced, and the proportion of grass and legume pastures decreases. In organic farming, crop rotation planning should above all take the soil into account. Choosing only commercial crops with the highest gross margins and largely abandoning temporary pastures amounts to programming serious long-term problems of soil fertility and plant diseases. A good crop rotation must increase the durable humus content in the long term or at least maintain a balanced humus budget and prevent the development of diseases, pests, and weeds.

Grass and legume pastures form the central element of any organic crop rotation because they allow the soil to rest, and humus content increases if they remain in place for several years. They prevent weed seeds from germinating and suppress diseases and pests, which are destroyed by the high activity of soil organisms. The longer the grass and legume pastures last, the more significant their residual effect. Three-year pastures effectively smother thistles. Due to their short duration, green manures can only partially replace grass and legume pastures.

Long and diversified crop rotations with a high proportion of soil cover and a diversification of soil work and harvest dates prove beneficial in the long term.

Important crop rotation rules for humus:

- At least 20% grass and legume pastures in the rotation to improve soil fertility and suppress weeds.

- At most 60% cereals to avoid diseases.

- Alternate leaf and stem crops, humifying and humus-consuming crops, autumn and spring crops, early and late sowings – to avoid soil depletion, soil-borne disease problems, and problematic weeds.

- Grow green manures to enrich the soil with nutrients and humus and to protect it against erosion.

Model examples of humifying and humus-consuming crop rotations

In practice, crop rotations heavily dominated by row crops often have negative humus balances. The following examples show that it is possible to achieve a balanced or even positive humus balance even with crop rotations including strongly humus-consuming crops and a livestock load of 0.5 to 0.8 LU per hectare.

Soil fatigue is a real challenge

If a species or group of plant species can no longer be normally grown on a plot after a cultivation interval of three to four years, the phenomenon is called soil fatigue. The best-known examples concern apple trees, roses, and legumes. Soil fatigue can be caused by accumulation of pathogens, by unbalanced depletion of certain essential soil elements, by toxins secreted by plants (allelopathy), by poor soil structure, or by a combination of some or all of these factors. Soil fatigue can become a real problem in organic farming when it concerns legumes. It manifests as a decline in vigor of grass and legume pastures and grain legume crops that worsens year after year and is caused by an imbalance in the soil (development of pathogens). Many interactions still unknown are currently the subject of scientific research. Treatments are mostly individual and require competent advice.

Organic fertilizers

Manure and slurry from animal production as well as composts and shredded plant residues from crop production are the main organic fertilizers in organic farming. Recently, more and more fermentation substrates (digestates) from biogas production plants are also being used. These organic fertilizers affect the soil in different ways depending on their physical characteristics (from liquid to solid), chemical (from simple minerals to complex organic molecules), and biological (single or diverse matter).

Compost

Due to its transformation, compost contains stabilized organic matter useful for humus formation and provides the soil with a nutrient mix rich in phosphorus. Increasing studies show that compost advances soil life and fertility more than other organic fertilizers: compost improves the soil. While manure compost ensures good nitrogen fertilization, green waste compost does not contain much nitrogen. In practice, composting municipal green waste together with one's own manure has proven effective, also economically; composting fees for green waste can cover the costs of a compost turner and labor. Each country has its own legal bases that must be respected. When young, lignin-rich composts are applied to fast-growing crops, this can cause – especially in spring – temporary nitrogen immobilization in the soil. In such cases, more mature composts, which already contain some nitrate, are more suitable. A supplementary fertilization with a readily available organic nitrogen source such as slurry can prevent this risk.

What should be considered when composting plant waste or manure?

- Compost must not be waterlogged (no water should come out when squeezed). Cover if necessary.

- Compost must not dry out. Water if necessary during turning.

- Turning the compost promotes its transformation.

- Adding soil (10%) promotes the formation of stable humus molecules.

- A fermentation temperature of at least 50 °C promotes hygiene and destroys weed seeds.

Slurry

Slurry contains a lot of rapidly available ammoniacal nitrogen and rapidly mineralizable organic matter which contribute little to soil humification. The rapid action and flexibility of slurry use during the growing period is its great agronomic advantage. Slurry should preferably be spread in wet weather on absorbing soils to minimize nutrient losses and pollution of air and water. Spreading large amounts of slurry causes ammonia formation that can burn earthworms near the soil surface. If well developed, soil life can nevertheless absorb moderate doses of about 25 m3 per hectare of diluted slurry to incorporate them into the food chain and thus reintroduce them into the organic matter cycle.

Manure

As a mixture of plant and animal matter, manure is a more balanced fertilizer than slurry, but its quality strongly depends on storage. Decomposed manure and mature manure compost are better for soil structure and yields than fresh manure or (putrid) manure heaps but do not feed earthworms. Even considering only nitrogen, composted manure proves to be the best fertilizer as it causes neither nitrogen immobilization due to poorly decomposed straw nor damage from large manure clumps. With prolonged storage, the quality of composted manure approaches that of compost. Loose housing manure is a special case that usually requires mechanical loosening before it can be decomposed and spread.

Correctly assessing nitrogen action

The nitrogen efficiency of a fertilizer depends not only on its nitrogen content but also on the carbon to nitrogen ratio (C/N ratio). For example, slurry has a C/N ratio of 7 ("narrow"), straw a C/N ratio of 50 to 100 ("wide"), and compost's C/N ratio is often between 20 and 30. Nitrogen fertilization acts quickly when the C/N ratio is around 10, and the higher the C/N ratio, the more organic fertilizers act long-term and contribute to soil humification. The speed of nitrogen uptake also strongly depends on the general nitrogen availability in the soil, e.g., nitrogen from legume root excretions, soil temperature and moisture, as well as the diversity and vitality of soil life.

Using digestates as fertilizers?

The possibility of using digestates as fertilizers has existed since the invention of biogas digesters. Digestates often consist of the same starting substrates as composts (slurry, manure, plant matter, etc.) and contain as many nutrients and organic matter. However, the effects of these fertilizers are very different due to different decomposition processes (composting and methanogenic fermentation): compost forms in the presence of oxygen during aerobic fermentation, and its organic matter is stabilized if decomposition has progressed sufficiently. Digestates, on the other hand, are produced under anaerobic conditions, i.e., by fermentations occurring in an oxygen-free environment analogous to rot, and they are still in the decomposition process when leaving the digester. Their use as fertilizers must therefore consider the following points:

- Liquid digestates contain a lot of ammonium (NH4+) which easily converts to ammonia (NH3) upon contact with air during spreading. Liquid digestates should therefore be spread – possibly after dilution – in cool, humid, and windless weather on absorbing soils with a hose spreader, a semi-rigid hose distributor with coulters, or a spreader equipped with a slurry incorporation system.

- Avoid anaerobic conditions that cause laughing gas (N2O) formation!

- Moist but solid digestates can act as fast fertilizers, but their contribution to durable humification is lower and they improve soil structure only slightly. If the digestate dries out, it loses its ammonia! Moist digestates can be re-fermented aerobically to produce good quality compost. To avoid ammonia losses, these digestates must be mixed with pre-decomposed lignified materials.

- Digestates should be applied only when the environment can assimilate the supplied fertilizing elements.

In organic farming, the use of digestates as fertilizers is only allowed under certain conditions (take into account the specifications of the different federations!).

Do organic farms have phosphorus deficiency problems?

On farms without external nutrient inputs, phosphorus can become a limiting factor in fodder or fertilizers. Inputs of manure or compost from outside sources would be a possibility to avoid phosphorus deficiencies without having to supplement fertilization with commercial raw phosphates. Growing legumes and promoting soil microorganism activity could also mobilize large amounts of phosphorus locked in the soil. Farms that have phosphorus deficiency problems in crops or livestock despite a balanced phosphorus budget often have soils with high pH. Indeed, high pH disrupts phosphorus uptake by plants.

Green manures and temporary pastures

There are many good reasons to grow green manures and temporary pastures: They contribute to improving soil quality, reduce rotation diseases, and help fix nutrients present in the air or mobilize them from the soil. For farms with little or no livestock, green manures are one of the most important ways to feed the soil and build humus. However, no green manure can satisfy all requirements and wishes at the same time. Different mixtures or single species come into consideration depending on the objective the green manure should achieve. Mixtures with grasses are generally recommended when the green manure should also serve as fodder. There are also good mixtures without grasses for non-fodder green manures.

There are plants for every objective

Goal: improve soil structure, humification

Temporary pastures based on grasses and legumes that remain in place for at least one and a half years are best suited for soil humification, as their roots intensively colonize the soil throughout its depth. Ideally, the mixture is mowed regularly (possibly to sell the fodder) and the last cut is incorporated as mulch. On the other hand, the more intensive root colonization and slower decomposition of grass straw more strongly promote humification. Mixtures with alfalfa are best for dry sites. Temporary pastures must remain in place for more than one year to have a lasting positive influence on the soil, but this increases the risk of wireworm attacks in subsequent crops.

Goal: protection against erosion during winter

For protection against erosion, it is best to sow a winter-hardy green manure at the right time, such as a mixture of grasses and legumes or a ryegrass after cereals, or forage rye (also a mixture of vetch and rye) or Chinese cabbage after potato or maize.

Goal: provide nitrogen to the following crop

The best nitrogen inputs are provided by pure legumes, for example peas or field beans or, for longer durations or post-harvest sowings, mixtures of clover and alfalfa. Dense stands of legumes that remain until flowering can provide between 70 and 140 kg N per ha to the following crop. Summer vetch and Alexandrian or Persian clovers are well suited for short swards of about 3 months during the season. Stubble from grass and legume pastures provides a gain of 50 kg N per hectare. Grain legumes, such as lupin, can not only fix nitrogen but also mobilize phosphorus for subsequent crops.

Goal: conserve nitrogen for the following crop

Fast-growing species such as forage oats, forage rye, mustard, or rape are best for conserving nitrogen for the following crop. Oil radish has the particularity of penetrating deep soil layers and recovering nitrogen that has migrated there. However, much nitrogen can be lost again if frost-sensitive species are not plowed before winter or if the following crop is established before winter. Many new species are currently being proposed for catch crops. These include Sudan grass, wild oats or oil guizotia (Guizotia abyssinica), which germinate quickly and suppress weeds well, and some resist drought very well. Experience will show which prove effective.

Green manures and climate

Frost-sensitive or winter-hardy green manures with a large green mass can emit large amounts of greenhouse gases (especially nitrous oxide) into the atmosphere during winter freeze-thaw cycles. Winter green manures sown before early September (depending on the climate region) should therefore be mowed in October, with the mowing removed from the field and valued, for example, as silage fodder.

Nitrogen quantities supplied by legumes

After mowing a mixture of grasses and legumes or a pure legume crop, the nitrogen residue can be roughly estimated as follows:

- Stubble of grass and legume mixture: + 50 kg N/ha

- Grass and legume mixture before the grasses' stem elongation: 15–25 kg N/ha per kg/m2 of fresh mass, which gives about 20–100 kg N/ha for a fresh mass of 1–4 kg/m2.

- Grass and legume mixture after the grasses' stem elongation (e.g. oats or forage rye): 0–20 kg N/ha, regardless of quantity because the C/N ratio is generally very wide.

- Pure legumes before flowering: about 30–35 kg N/ha per kg/m2 of fresh mass. Dense stands reaching knee height reach about 3–4 kg/m2, thus 80–140 kg N/ha.

Goal: deep loosening

Here come into play oilseed radishes and perennial alfalfa stands. The soil must first be deeply loosened with an appropriate chisel so that the roots of the green manure plants penetrate more easily into the deeper soil layers and can stabilize the new pores there (colonization by living organisms). To be effective, oilseed radishes also need a cultivation period of at least 3 months. Like other deep-rooted legumes, lupin and faba bean can be used for deep root colonization of the soil.

Goal: disease and pest prevention

Green manures should help reduce disease and pest pressure for the following crop, so species closely related to the main crops should not be sown (e.g. no mustard if the rotation includes oilseed rape or cabbages). Peas should not be grown too often in the crop rotation. The same applies to other legumes, but to a lesser extent. Green manures based on legumes for threshing thus have no place in crop rotations where they are main crops. Special attention must be paid to diseases and pests attacking many different host plants such as sclerotinia, rhizoctonia, and certain species of nematodes. Green manures very sensitive to certain diseases (e.g. sunflower regarding sclerotinia) should be avoided if the rotation includes other sensitive main crops (oilseed rape, sunflower). Overwintering green manures can help circumvent crop rotation problems. For example, root-knot nematodes cannot multiply on winter peas and vetch if these crops are plowed early enough.

Goal: weed suppression

Weeds propagated by seeds can be suppressed by fast-growing green manures. Mixtures that tolerate a cleaning cut after emergence once they reach 10 to 15 cm height are often even better because they then form very dense and very lush stands. The best way to suppress perennial weeds such as thistles and bindweeds is to establish perennial mixtures of grasses and legumes.

Favoring weeds instead of fighting them?

Most wild weeds originally come from riverbanks or special places where the soil was continuously disturbed. They only arrived in Central Europe with cereals, invading fields as "weeds". Over time, they adapted to certain soil and light conditions. They are therefore often specialized, and some even manage to benefit from extreme conditions such as compacted soils.

Europe has up to 650 weed species. Different plant associations form depending on soil acidity and the crop in place (cereals or row crops).

Due to the use of herbicides, intensive fertilization with nitrogen, seed cleaning, clever agricultural techniques, and highly productive crop varieties, the living conditions of these weeds have massively deteriorated, and today 40% (D) to 80% (CH) of these species are on the "red list". After so many years of conventional agriculture, it sometimes happens that the seed bank is so depleted that many site-typical species are still missing several years after conversion.

How to favor threatened weeds?

The following measures can help conserve threatened weeds:

- Work the soil superficially.

- Regularly introduce periods of fallow.

- Choose wide row spacing or broadcast sow crops.

- Delay stubble cultivation and allow sheep or cattle grazing.

- Reintroduce old typical regional crops such as flax, buckwheat, or millet.

- Limit perennial fodder crops (but conflicting objectives with soil fertility!)

Diversify use – also for the soil

Weeds are vital resources for many beneficial organisms, favor pollinator species, and divert pests from crops. Weeds also promote crumb structure of the soil as they ensure root colonization and protection against direct sunlight between crops. And on fields left bare for a long time, such as maize, they can protect the soil against erosion.

From weed to problematic weed

Wild plants have always been fought because they compete with crops for water, nutrients, light, and space. Species well established in cultivated fields have adapted to this struggle, but many species do not cause problems because they have low competitive strength. However, some species are capable – especially when growing conditions are poor – of outcompeting crops. Plants that can reproduce rapidly via roots or rhizomes such as thistle, bindweed, rumex, or couch grass represent a major challenge for organic large-scale crops.

Balanced crop rotations, careful soil work, and good starting and growing conditions for crops often decisively contribute to relegating wild plants to the status of weed flora that can overall have positive effects on soil fertility and yields.

Soil work stimulates weeds!

Even light and superficial, any soil work stimulates wild plant germination. In case of heavy weed emergence, it is possible to regulate them by repeated superficial stubble cultivation or several phases of false seedbeds. Only once the above possibilities have been thoroughly considered and well coordinated should it be decided whether weeds must be controlled with special machines or other means.

Soil compaction and ways to avoid and remedy it

Soil compaction – Damage caused by machinery

Soil compaction occurs when the pressure exerted on the soil by vehicles exceeds its bearing capacity. Whether clayey or sandy, all soils can be compacted. Harmful compactions appear very quickly in clay soils, while fertile loamy soils on loess seem to tolerate more errors. However, they also suffer compaction, but yield losses often only become noticeable in years with extreme weather conditions. In sandy soils, small proportions of silt or clay are enough to increase susceptibility to compaction.

Soil compaction primarily means that the oxygen and water supply network is destroyed. Soils then absorb water less well, which instead of penetrating deeply runs off on the surface. The living conditions of soil organisms and roots deteriorate because gas exchange – and thus oxygen – is lacking. Even geologically deep soils become ecologically superficial due to compaction, because roots can no longer reach the deep soil layers.

"Having the courage to wait helps avoid mistakes"

Soil moisture most strongly determines its bearing capacity because water acts as a lubricant between soil particles. Soil structure is no longer bearing when there is too much water. Waiting until the soil is well dried out and bearing requires strong nerves, but it is worthwhile in the long term. A forward-looking crop rotation and an appropriate choice of varieties that allow some leeway for sowing and harvesting dates can be very useful in this context. In autumn, catch crops remove water from the soil and make it more bearing for autumn sowing.

What to do in case of soil compaction?

It can happen that mechanical subsoiling causes the subsoil to lose even more structure and worsens the compaction one wanted to eliminate. To avoid this, the following points must be considered:

- Subsoiling should only be done when the soil is dry at working depth.

- Stabilize the loosened structure by sowing, if possible in the same pass, perennial deep-rooted plant species (e.g. grass and legume mixture, alfalfa).

- Change working methods to avoid repeating the same mistakes.

Soils are more bearing if worked less often and less deeply. In untilled soils, earthworm and microorganism activity develops an uninterrupted pore network that ensures sufficient air and water circulation. However, this observation can cause conflicts with mechanical weeding methods.

Tire internal pressure corresponds approximately to the pressure on the soil surface down to about 10 cm depth. This clearly shows that tire pressure should be low. It is best to use modern radial tires that allow working at very low pressure in the fields. Trailers equipped with truck tires therefore have absolutely no place in the fields!

To know how far tire pressure can be reduced, one must know the load per wheel (axle load at weighing divided by two) and then find in the tire pressure table provided by the manufacturer the minimum recommended pressure for the measured wheel load and travel speed. This method increases traction transmission and reduces slipping and thus surface smoothing of the soil.

It should also be known that the higher the load per wheel, the deeper the pressure acts in the soil, almost independently of the contact area of the wheels with the soil and tire pressure. Wide tires can thus protect against superficial compaction but not against subsoil compaction when the load per wheel is very high. Working with lighter trailers, machines, and tractors thus better preserves the soil. And this allows using tires inflated to pressures below 1 bar.

It should also be known that the more often one drives on soil, the more it compacts under the wheel tracks. Reducing the number of passes as much as possible to meet soil needs thus improves fertility and saves money.

Soil erosion and ways to avoid it

All mechanical interventions in the soil reduce soil cohesion and decrease the energy required to wash away soil particles. Soils freshly worked and without vegetation cover are vulnerable to raindrop impact and surface runoff even if slightly sloped. Organic farming generally provides favorable conditions to reduce water and wind erosion: low proportion of wide-row crops particularly sensitive to erosion, grass and legume pastures that cover the soil well and whose residues stabilize soil aggregates after breaking. However, there remain periods without vegetation cover, and the "clean slate" obtained by plowing remains the most common practice.

Seeding three soil layers (0–20 cm, 20–30 cm, and 30–60 cm) under a 700-year-old pasture simulates well the effect of erosion: while soil structure and crop emergence in the upper layer are good, emergence and structure of lower layers are poor due to water and crusting. One can thus well imagine the loss of soil fertility after the topsoil has been lost by erosion.

Effective techniques against erosion

- Plant hedgerows across slopes. Dividing an erosive slope of 200 meters length into two slopes of 100 meters length reduces soil erosion by one third.

- Establish buffer zones as wide grassy strips with, if possible, trees and bushes.

- Work if possible perpendicular to the slope.

- In fields highly threatened by erosion, completely avoid wide-row crops (e.g. maize) or those requiring frequent soil work (e.g. vegetables).

- Cover the soil with catch crops and cover crops.

The deterioration of the superficial structure of a soil is a warning signal that every responsible farmer should take seriously! Good vegetation cover and well-nourished biomass in the upper part of the arable layer are the basic conditions for sustainable agriculture. Soils fed with organic matter and biologically active are better able to absorb rainwater and maintain good surface structure despite raindrop impact, offering better protection against crusting and erosion.

The future of soil cultivation

Taking climate into account

Agriculture and global warming are strongly interdependent. Indeed, on one hand agriculture is threatened by global warming: worldwide, increasing droughts, extreme precipitation, and erosion pose problems for food production. On the other hand, agriculture is responsible for 10 to 15% of total greenhouse gas emissions – and if input industry (fertilizers, pesticides) and land conversion by deforestation are included, this proportion rises to up to 30%.

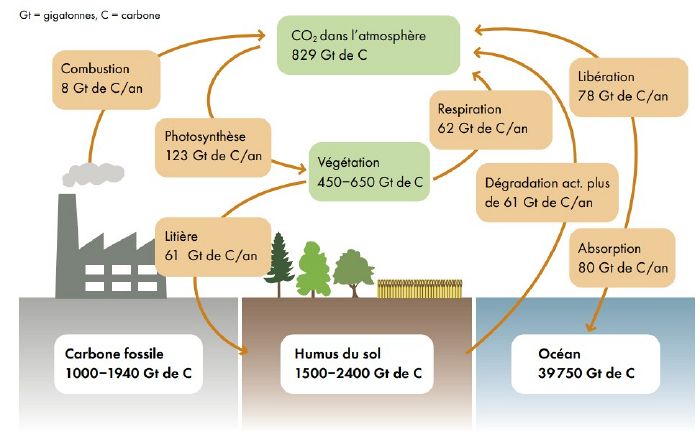

The Importance of Soils in the Global Carbon Cycle

Photosynthesis allows plants to form organic carbon molecules by consuming atmospheric CO2. Unless these molecules leave the fields as harvests, they eventually end up in the soil as root residues, root exudates, and plant litter. The pedosphere (all soils) is the largest carbon sink of the living Earth (the biosphere) after the seas and oceans! The humus and soil life of the Earth contain about 1,600 billion tons of carbon (Gt C), significantly more than the atmosphere (780 Gt C) and vegetation (600 Gt C – mostly in the form of wood) combined. In the soil, the carbon from plant residues and organic fertilizers is partly transformed into humus and partly released as CO2. Humus consists of about 60% carbon. With a C content of 1% (which corresponds to about 1.7% humus), the topsoil sequesters approximately 45 t of C per hectare.

The rate of transformation and decomposition of organic matter varies from a few days or weeks for fresh plant materials to several years or decades for straw, manure, or mature compost, and even up to centuries or millennia for very complex humus. The more humus molecules are linked together and to clay minerals, and the more they are incorporated into structurally stable soil aggregates, the better they are protected against decomposition processes.

The Role of Soil in the Carbon Cycle

The Carbon Sequestration Potential of Organic Farming Soils

Comparisons of systems worldwide show that organic farming systems can bind about 500 kg more carbon per hectare per year than conventional systems. Soils store more carbon during the first 10 to 30 years after conversion, then another equilibrium is established. However, even in organic farming, the existing humus cannot be permanently preserved if crop rotations are heavily simplified – and even more so if grass and legume pastures are no longer among the main crops. Intensive tillage also stimulates humus degradation, not to mention that it consumes a lot of petroleum.

Extensive studies conducted in Europe show that most soils currently emit more carbon than they fix, notably because the already occurred increase in average temperatures accelerates humus degradation and thus self-amplifies. But these studies also show that, in practice, only a minority of farms utilize their humification potential!

Methane and Nitrous Oxide

Methane (CH4) has a greenhouse effect 20 to 40 times more powerful than CO2. Living and well-aerated soils remove methane from the atmosphere and decompose it. On the other hand, methane production is caused by farm fertilizers. Composting (e.g., manure) produces much less methane than other farm fertilizers.

Nitrous oxide (N2O) has an even stronger greenhouse effect, 310 times more powerful than CO2. Soils produce it when they lack oxygen – even for a short period. The higher the amounts and concentrations of nitrogen supplied by fertilizers, the more N2O the soil can produce. Therefore, it is necessary not only to avoid excessive concentrations of mineralized nitrogen (Nmin) in the soil solution but also to ensure good natural aeration and permeability of soils. Studies have shown that ammonium-rich organic fertilizers have a high potential for N2O losses. Such fertilizers, like pig slurry or methanized slurry, can be as harmful as ammonium nitrate. The great art of agriculture is thus to adjust nitrogen inputs and the mineralization of organic nitrogen molecules to the real needs of plants. Turning grass and legume pastures early and shallowly and immediately following them with another crop helps to limit N2O emissions produced during winter after freeze-thaw cycles due to "undigested" plant residues.

Improving the Stability of the Agricultural Ecosystem

In Europe, human-induced climate change will cause modification of weather conditions and an increase in extreme events. Organic farming can prepare for this in order to produce sufficient harvests even in bad years.

The main challenge is to cope with too much or too little water, as this affects plant production in terms of resistance to diseases and pests. The resistance to lodging of certain crops could also become critical due to increased storm events.

- The most important factor in crisis situations is a very active and diverse soil life. A good network of soil organisms helps plants receive enough nutrients and water even in shortage, but also, when weakened, to find help against diseases and pests from the soil-plant immune system.

- A permeable soil structure not only prevents oxygen deficits but also protects against flooding and reduces risks of surface water erosion and runoff or rill erosion. Organic farming also needs light machinery that reduces soil compaction risks.

- Complete soil cover reduces water loss, and groves such as hedges or agroforestry slow drying winds, and the shade provided by trees or other crops can be an advantage for some crops (except in very humid conditions) because they do not have to close their stomata to protect against evaporation.

- Humus can store up to 3 to 5 times its weight in water. An increase of 1% in humus content allows the soil to store 40 mm more rainwater in a plant-available form. Reduced tillage enriches the topsoil in humus, which increases its permeability and water retention capacity.

- The soil must remain deeply penetrable by roots, so the formation of hardpan layers must be avoided. This especially allows deep-rooted plants like alfalfa, oil radish, or sunflower to better survive dry periods.

- Varieties selected under organic conditions must cope with more weeds and pathogens than those grown with fertilizers and chemicals. They are therefore more selected for disease resistance and competitive ability. Another selection criterion is, of course, resistance to lodging.

- Drought resistance depends on various selection aspects (cell wall thickness, stomata, etc.) but also on the balance of nutrients available during growth. Avoiding soil salinization with fertilizers is self-evident in organic farming.

- Intercropping increases yield stability because some plants perform better depending on weather conditions and can compensate for yield decreases of weaker plants. Diversifying crops can stabilize the overall yield of a farm.

Summary: the higher and more self-sustaining the soil fertility is, the better plants can tolerate stress and resist extreme weather conditions. All recommendations in this brochure also serve to better guarantee yields in bad years, but for this, varieties and machinery adapted to weather whims are still needed.

Ideas for the Future of Organic Agronomy

Organic farming has already achieved much during its development to become what it is today. The soil-plant organisms managed organically are themselves more fertile and more stable than artificially nourished systems, which are highly technological and have low self-regulation. But the larger the areas occupied by a single species or few species in the crop rotation, the further the agricultural ecosystem is from the dynamic equilibrium observed in natural grasslands and forests. Nature does not like monocultures. However, agriculture fights biodiversity that nature strives to reintroduce into cultivated fields with large external energy inputs; for example, using fuel for mechanical weed control and artificial soil structuring. To be consistent and able to do things differently and more in line with the true needs of soil fertility, all actors in organic farming must be innovative and visionary. Here are some ideas:

- Pay less attention to peak yields and more to overall yields. Since extremely high peak yields of a crop can only be obtained with very narrowly improved, sensitive varieties that require much care, sustainable agriculture must abandon the industrial ideal of maximum peak yields. Instead, it can aim for a yield that is both optimal for the whole system and sufficiently robust against extreme weather events. This may lead us towards intercropping producing both food and fodder and energy sources, not forgetting other "harvested services" such as climate protection, resource reuse, and maintaining a sustainable water cycle at the regional level.

- Improve and differentiate our collaboration with soil organisms. We can deepen our agricultural partnership with earthworms, mycorrhizal fungi, rhizobial bacteria, and many other soil organisms, and our agricultural techniques must also learn to respect them. It is possible to promote their living conditions by selecting agricultural practices such as host plant cultivation, intercropping, grass and legume pastures, gentle tillage, and selection of adapted varieties. It is also necessary to check whether in some cases inoculation with root bacteria (as is already standard for soybean), mycorrhizal fungi, or other specific microorganisms is needed.

- Organic farming needs different varieties. Instead of current varieties that cannot survive without "solitude," we need "socially competent" varieties that perform well even under conditions closer to nature. Perhaps long-straw cereals will find a new place in the sun by themselves, with much larger ears but less dense stands? There may be perennial varieties, a good perennial rye, perhaps intercropped with a lower stratum of legumes, or even with cumin or parsnip…?

- Machines in harmony with nature. Future agriculture does not need to be opposed to technology. It is indeed possible to use machines and devices that respect Nature and Creation – and thus do not fight them or contradict the advantages of organic farming. Concretely, this could mean: Light vehicles instead of "agricultural tanks"? Combine harvesters that also collect weed seeds instead of blowing them onto fields? Perhaps even selective weeding or harvesting machines capable, thanks to sensors and electronic control, of navigating intercropping?

- Cultivating the soil requires education and culture. It is not technology but humans who are responsible for whether agriculture is sustainable or not. The fertile nature of soil needs a fertile human nature – and cultivated soils need cultivated people. This complements the maxim "healthy soils – healthy plants – healthy animals and humans." Will this in turn lead us to more training and extension work than control and respect of standards and directives? Training and extension work that would again focus more on our values and visions and less on economic, commercial, and societal conditions? With more mutual exchanges and advice for the development of life and the farm before adequate technical and economic advice?

- Sustainable development requires renewal of forces and resources. Humans and soils become exhausted when they give more than they receive. Exploitation cannot be sustainable. Ensuring sustainable development also means strengthening local, regional, and global cycles again and remaining open to system changes. The future will show whether we will compost human excrements or bury ashes and charcoal produced by farm wood heating in the soil. What is certain is that it will be important that fieldwork only uses energy resources that truly meet sustainability criteria.

- Perspective: visions are first individual then societal. Our agriculture still has much to do if it wants to sustain itself for centuries and millennia. We will need to continue having the courage to be visionary and the strength to experiment and learn from failures to make our agriculture truly sustainable and future-oriented. The fact that the new development of soil management in organic farming cannot be achieved through strengthening the requirements of standards corresponds to the very essence of soil fertility and a positively creative image of humanity. This development will indeed need freedom and individual development as well as mutual exchange and support.