Earthworms

Earthworms are usually the most abundant soil animals in agricultural soils. They are known to improve physical, chemical and biological properties of soils. Together with soil microorganisms they have a great potential to enhance soil fertility. Although much is known about the general taxonomy and biology of earthworms, knowledge about their impact on soils, their interactions with other soil organisms and the influence of farming practices on their populations is increasing only slowly. This guide summarises the knowledge on earthworms. It gives an overview of the biology, ecology and the multiple services of earthworms to agriculture, and provides recommendations for the promotion of these extraordinary organisms in agricultural soils.

Underestimated soil workers

In the 19th century, earthworms were considered a soil pest. Even though this view has completely changed, they still don’t receive sufficient attention in agricultural practice. Few farmers actively promote them. Instead, heavy machines, intensive tillage and wide use of pesticides have in many places eliminated or drastically reduced earthworm populations. In contrast, in a naturally managed grassland soil of one hectare up to three million earthworms can be found. Number, biomass and diversity of earthworms in a soil are considered an important criterion of soil fertility, as a rich earthworm fauna contributes in many ways to healthy and biologically active soils, which again favour many positive ecosystem services and involve a better resilience and adaptation of farming systems to climate change. Due to their numerous contributions to increase sustainability of agroecosystems, earthworms should receive more attention and be specifically promoted in sustainable farming – and especially in organic farming.

Distribution and biology of earthworms

Distribution

With the exception of polar regions and deserts, earth worms (Lumbricina) can be found in most soils. While more than 3.000 species are known worldwide, only 400 species are found in Europe and 40 species in Central Europe. In crop land, only 4 to 11 species are commonly found.

Soils

Earthworms prefer medium-heavy loam to loamy sand soils. Heavy clay and dry sandy soils are not favourable to their development and limit their spreading. In acidic peat soils, only specialised species are found that have adapted to such unfavourable soil conditions.

Climate

Earthworms cannot regulate the body temperature themselves. Therefore, when it is very dry and hot, many earthworms estivate and retreat to deeper soil layers. With low winter temperatures, the worms retreat to frostfree portions of their burrows, and their metabolism slows down to the minimum. During frostfree winter days, they become active again. In spring and autumn, earthworms are most active. Earthworms are intolerant to drought. They are active only when the soil is moist, and are inactive when it is dry. As earthworms can lose up to 20 % of their body weight each day in mucus and castings, they need moisture to stay alive.

Development

Earthworms develop slowly, with the exception of the leaf litter dwellers (e. g. compost worms). They produce only one generation with a maximum of 8 to 12 cocoons (eggs) per year. Earthworms live 2 to 10 years, depending on the species.

Reproduction

Earthworms are hermaphrodites. Sexually mature worms can be identified by the ‘genital belt’ (clitellum) encircling the body. Peak burrowing activity and reproduction in the temperate zone take place in March and April and also in September and October.

Mobility

Earthworms can migrate into cropland from undisturbed edge areas like field margins. The night crawler (Lumbricus terrestris) can migrate as far as 20 metres per year. Birds and livestock contribute significantly to the dispersal of earthworms.

Feeding

Earthworms primarily feed on dead plant parts but don’t have the digestive enzymes to break down the cellular structure of plant materials. Therefore, they mix plant biomass with mineral soil for digestion. To meet their daily calorie needs, they have to eat 10 to 30 times their own body weight.

At night, they graze on the lawns of algae that have grown on the soil surface during the day and pull dead plant parts into their burrows for ‘predigestion’ by soil microorganisms in 2 to 4 weeks. As earthworms do not have teeth, they cannot feed on roots. In order to thrive, earthworms require a rich food supply of plant debris such as dead roots, leaves, grasses and organic manure.

Services of earthworms for agriculture

Earthworms affect many ecoservices that relate to soil fertility and plant production. Hence, the promotion of earthworms and other critical soil biota helps making more efficient use of ecological processes. The improvement of abiotic and biotic soil properties by earthworms entails numerous benefits for farmers such as an increase of nutrient availability and water storage in soils, reduced erosion, and improved farm productivity.

Earthworms aerate the soil

Earthworm burrows increase the amount of macropores and thus contribute to a good aeration of the soil.

Earthworms facilitate root growth

Over 90 % of the burrows tend to be colonised by plant roots. Earthworms leave a major part of their nutrient-rich casts in their burrows. This provides a favourable environment for the growth of plant roots. Thanks to the burrows, plant roots can more easily penetrate into deeper soil layers, finding nutrient-rich earthworm casts, water and air. Earthworm burrows also help incorporate surface applied lime and fertiliser into the soil.

Earthworms improve water infiltration into soils and reduce surface runoff

The stable burrows of the vertical burrowers, in particular, considerably improve water infiltration, storage and drainage of soils. Surface runoff and erosion are thus reduced. Soils with earthworms drain up to 10 times faster than soils without earthworms.

The vertical burrows, stabilised with slime, can be as deep as 3 metres in deep loess soils, and even as deep as 6 metres in chernozem soils (i. e. black earths). Due to their powerful muscles, deep burrowers are able to penetrate slightly compacted soils and thus improve drainage.

Up to 150 burrows – or 900 metres of burrows per square metre and metre of depth – can be found in unploughed soil. In zero-till soils, where worm populations are high, water infiltration can be up to 6 times greater than in cultivated soils.

Earthworms incorporate dead plant matter into the soil

Earthworms incorporate organic material such as crop residues, organic manure, dung or mulch into the soil. They fragment, mix and digest plant debris through physical grinding and chemical digestion. This accelerates the decomposition of the dead plant matter and thus stimulates the nutrient cycling in the soil-plant system. When earthworms draw down plant materials into the burrows, they relocate valuable nutrients throughout the soil, especially to the deeper soil layers. Under grassland conditions, earthworms incorporate up to 6 tons of dead organic matter per hectare per year into the soil. In forests, earthworms process as much as 9 tons of foliage per hectare.

Earthworms decompose dead plant matter and increase plant nutrients

Earthworms produce 40 to 100 tons of casts per hectare annually. The worm casts form stable soil aggregates or crumbs, which are deposited on the soil surface or in the soil. Organic and inorganic fractions are wellmixed in worm casts, and the nutrients are present in a readily available and enriched form. The casts contain on average 5 times more nitrogen, 7 times more phosphorus, and 11 times more potassium as the surrounding soil. The nitrogen in the casts is readily available to plants.

Earthworms rejuvenate the soil

Earthworms transport soil material and nutrients from the subsoil to the topsoil and thus maintain respectively foster the vitality of the soil.

Earthworms help improve soil structure and soil stability

By the intensive mixing of organic matter with inorganic soil particles and microorganisms and by slime secretion, earthworms create stable soil crumbs, which enhance soil structure. Soils with high earthworm activity have less tendency to become muddy and can be worked more easily than soils with low earthworm activity. In addition, nutrients and water are more effectively retained in the soil. Abundant worm casts production makes heavy soils looser and sandy soils more cohesive.

Earthworms act as biocontrol propagators

Earthworms promote the colonisation and propagation of beneficial soil bacteria and fungi in their burrows and casts. By pulling fallen leaves into the soil, foliar pathogens and pests – i. e. winter stages of fungal pathogens such as apple scab, and insects such as leaf miners – are biologically degraded.

Earthworms help control soil-borne pests

Scientific studies show that earthworms promote the growth and propagation of beneficial organisms in the soil. Earthworms distribute insect-killing nematodes (e.g. Steinernema sp.) and fungi (e.g. Beauveria bassiana) in the soil, thus contributing to a better natural regulation of soil-borne pests. Dormant forms, like fungus spores, however, resist digestion in the earthworm gut and are excreted in casts.

Earthworms support carbon sequestration

Earthworms ingest organic residues of different C : N ratios and convert it to a lower C : N ratio and finally contribute to carbon sequestration. By doing so, they help mitigate climate change.

Ecological groups of earthworm species

Earthworms are classified into three main eco-physiological categories (see also Table 1, page 7):

- Leaf litter or compostdwelling worms : theyare nonburrowing and live at the soil-litterinterface and eat decomposing organic matter.These worms are epigeic species.

- Subsoil-dwelling worms : they feed (on soil),burrow and cast within the soil, creating horizontal burrows in the upper 10–30 cm of the soil. These earthworms are endogeic species.

- Top-soil dwelling earthworms that constructpermanent deep vertical burrows : they use the burrows to visit the soil surface to obtain plant material for food (anectic species).

In agriculture, vertical burrowers play a key role (higher biomass and bioturbation, permanent burrows, water infiltration into the soil). For arable and forage production, all burrowing worm species (i. e. endogeic and anectic species) play an important role. Shallow burrowing worms contribute to improving soil fertility and structure in the topsoil, whereas the vertical burrowing earthworms contribute to noticeable soil improvements in deeper soil layers by bringing organic matter into deeper layers and improving soil aeration and water retention with their vertical tunnels. Latter also promote deeper rooting of arable soils, which tends to lead to higher yields as more nutrients are available.

Surface-dwelling earthworm species (epigaeic species) are of particular importance for the decomposition of litter material and in composting (see Box 1).

Box 1 : Critical role of epigeic worm species in vermicomposting

Vermicomposting is a process using various epigeic worm species to decompose organic waste and produce a nutrientrich organic fertiliser and soil conditioner for small-scale farming. The qualities of the vermicompost are essentially due to the high nutrient content of the earthworm casts.

Estimation of the number of earthworms in a soil

Earthworm numbers vary widely in different soils depending on soil type, rainfall and farming practices. In arable soils, their number may range from 30 to 300 individuals per square metre. In Central Europe, 120 to 140 worms per square metre make a good population density for intensively cultivated cropland. This corresponds to 90 to 110 g of earthworm biomass per square metre.

As a means to easily assess the earthworm population in a certain field, the approximate number of worms can be roughly estimated using the following methods:

- Number of worms: 5 samples of 10 × 10 cm and 25 cm deep spade full of fertile, medium-heavy loam soil contains in average 2 to 3 worms. This amount corresponds to 100 to 200 worms per square metre.

- The number of worm burrows is also a good indicator of worm activity in the soil.

- When counting the number of casts (worm droppings) on a 50 × 50 cm area during the pe riods of earthworm activity (March to April and September to October), 5 or fewer casts indicate little worm activity, 10 casts indicate moderate worm activity, whereas 20 or more casts indicate good worm activity with the soil containing many worms.

Box 2 : Habitat related earthworm density

The colonisation of a habitat by earthworms primarily depends upon food and water supply. Accordingly, there is considerable variation in the number of earthworms per square metre:

- Low-input pasture : 400–500 earthworms

- Fertilised meadow : 200–300 earthworms

- Hardwood forest : 150–250 earthworms

- Low-input arable field : 120–250 earthworms

- Poor grassland : 30–40 earthworms

- Spruce forest : 10–15 earthworms

Effective agricultural practices to enhance earthworms

Earthworm populations tend to increase with higher soil organic matter levels and decrease with intensive soil disturbances, such as tillage and the use of harmful chemicals. Implementation of appropriate measures can decisively promote earthworms and in a broader sense soil fertility. Thus, it is key to understand what measures spare or promote earthworms.

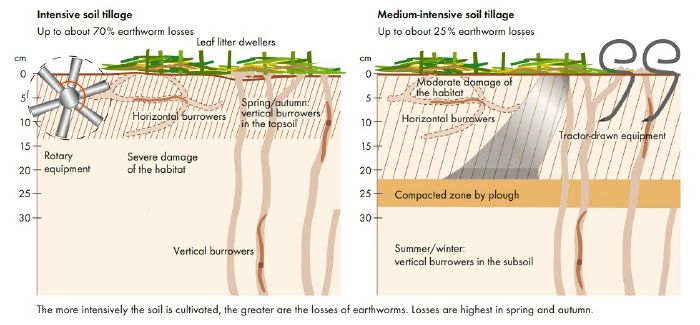

Avoiding intensive soil tillage and minimising the use of the plough

- Ploughs and fast-rotating devices can greatly damage earthworms. Loss rates of earthworms after the use of ploughs are about 25%, and can be as high as 70% with the use of rotary devices. Therefore, ploughs and fast-rotating devices should only be used if absolutely necessary and when earthworms are less active in the topsoil.

- Tillage of dry or cold soils has much lower negative impacts on earthworm populations, as the majority of the earthworms have retreated to lower soil layers during such periods.

- The use of on-land ploughs and shallow ploughing reduces compaction of deeper soil layers.

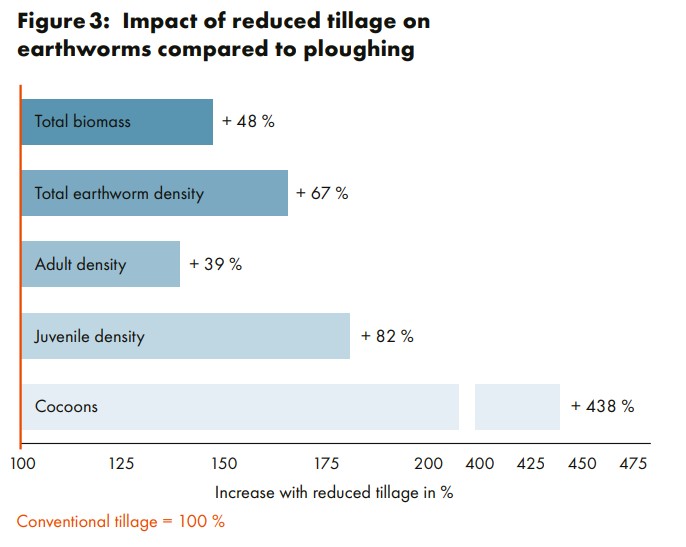

- Conservation tillage, which includes reduced tillage, minimises soil disturbance, lowers the risk of soil compaction, increases food supply, and conserves soil water. These enhance the density and biomass of earthworms (as well as of soil microorganisms in general).

With conventional inversion tillage, earthworms are injured and killed directly. More over, they become exposed to harsh environmental conditions and predators and, in the case of anectic species (vertical burrowers), their burrows are destroyed and their food sources buried. As the numbers above indicate, reduced tillage results in asignificant increase of earthworm population density, biomass and growth stages compared to ploughing, according to the results from an organically managed clay soil (Kuntz et al. 2013).

Minimising ground pressure and soil compaction

Earthworms need reasonably aerated and ‘loose’ soil. Compaction of the soil has negative implications on earthworm populations, other soil organisms, and biological processes in the soil, in general. Earth worms have difficulty to dig through heavily compacted soil. Therefore, soil compaction should be avoided or at least minimised.

What to consider :

- Adapt agricultural machinery to keep ground pressure to a minimum, reducing especially tyre pressure.

- Where possible, use light weight machinery. The lighter the equipment, the lower the compaction of the soil.

- As wet soils are especially sensitive to soil compaction, cultivate only well-dried, good bearing soils.

- Drain or mound arable soils that tend to waterlogging.

Diversifying crop rotation to provide food for earthworms

Diversified crop rotations with a good soil cover and a regular supply of organic matter provide favourable living conditions for earthworms.

What to consider

- Permanent grassland is ideal for earthworms. It provides high amounts of organic matter from leaves and roots. Pasture slashings and decomposed manure from grazing animals are also good sources of organic matter.

- Diversified crop rotations with longlasting and deep-rooted catch crops (rich in clover) or green manure crops, and diversified crop residues are the basis for a good earthworm population. Rota ting grassland/grassclover meadows with annual crops helps build up organic matter levels and promotes the earthworm fauna.

- Green manures are cultivated for high biomass production and turned into the soil at maximum biomass stage to provide organic matter to benefit the subsequent crop. Crops can also be grazed or slashed and then left on the surface for decomposition.

- Crop stubble is an important source of organic matter. Burning stubble destroys the organic matter in the top soil layers, which affects earth-worm at the surface. Ideally, the stubble is left to rot on the soil surface and the following crop is sown directly into the stubble (tricky with organic) or after minimal tillage.

- Groundcover such as grassland/grassclover meadows or stubble reduce soil moisture evaporation, thus keeping the soil moist. Organic matter cover also helps reduce the effect of climatic extremes, i. e. as heat and frost.

- As soil humus holds moisture in the soil, an increased soil organic matter content not only contributes to a better water supply for crops during drought, but also to more balanced living conditions for earthworms.

- 2-year grass-clover meadows within a crop rotation regenerate earth worm populations substantially. Multi-annual grass-clover is more beneficial than a 1-year grass ley.

Appropriate fertilising according to soil properties and plant needs

Both the type and the amount of fertiliser that are used affect earthworm populations. What to consider :

- An adequate and well-balanced fertilisation is favourable for both the crops and the earthworms.

- Slightly-rotted composted manure contains more food for earthworms and, thus, is better suited to promote earthworms than ripe compost.

- Organic fertilisers should only be incorporated to a shallow depth. Deeply buried crop residues are detrimental to earthworms as they can create anaerobic conditions during decomposition.

- Since ammonia in unprocessed liquid manure is toxic for many organisms and thus very harmful especially to earthworms living near the surface in waterlogged soils, liquid manures should be stirred (and thus aerated) and diluted prior to their application.

- Liquid manures should be applied to absorbent soils only and in moderate amounts of not more than 25 m3 per hectare.

- Most earthworms prefer a soil pH of 5.5 to 7.5. To ensure an optimal soil pH, lime should be applied routinely on the basis of pH measurements.

Box 3 : Key measures for the promotion of earthworms

The following measures are pre-requisites for the flourishing of earthworms in agricultural soils :

- Provision of sufficient plant material to earthworms on arable land with permanent ground cover also during winter

- Abstaining from the use of pesticides that are harmful to earthworms and other beneficial organisms

- Implementation of gentle soil cultivation methods such as reduced tillage and no-till to promote soil fertility

- Avoidance of soil compaction and promotion of well-structured and aerated soils using adapted machinery

- Site and crop appropriate fertilisation

- Continuous supply of fresh and dry organic matter throughout the crop rotation

Negative impact of non-organic agricultural practices on earthworm populations

Use of harmful pesticides

Various pesticides (including seed coating) can increase individual mortality, decrease fecundity and growth, and disrupt enzymatic processes. Moreover, they can change individual behaviour of earthworms reducing for example their feeding rate and finally decreasing their overall community biomass and density. Shallow dwellers (i. e. endogeic species such as A. caliginosa) on arable land, which continuously extend their burrows as they feed in the subsurface soil, are most susceptible to toxic pesticides incorporated into the soil. In contrast, earthworm species that live in deeper layers (i. e. anectic earthworms such as Lumbricus terrestris) are less susceptible to surface application of pesticides.

Insecticides and fungicides are the most toxic pesticides impacting survival and reproduction, respectively. Some fungicides, such as Bordeaux mixture or other copper sprays (also allowed in organic farming) reduce earthworm numbers in the soil when applied in high amounts, such as commonly done in orchards and vineyards.

In general, most herbicides do not harm earthworms directly, if they are applied at recommended rates of use (with exception of synthetic burn-off agents). Yet, they tend to indirectly reduce earthworm populations by decreasing the availability of organic matter on the soil surface as they inhibit the growth of weed plants. Especially in crops and rotations with no or little ground coverage, weeds are an important feed source for earthworms.

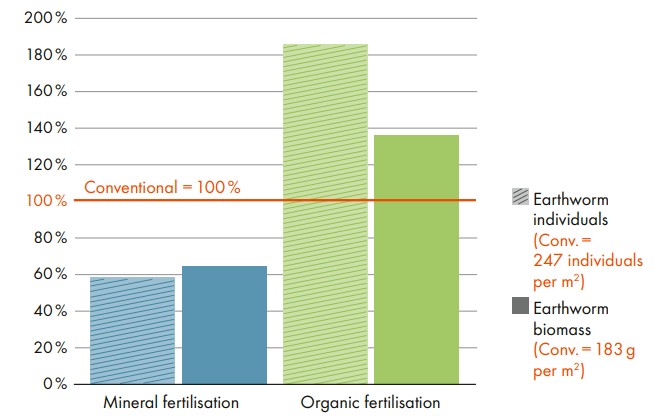

Use of mineral fertilisers

Most synthetic mineral fertilisers may not harm earthworms directly. However, ammonium sulphatebased fertilisers can be harmful to earthworms, possibly due to an acidifying affect. Furthermore, the use of high levels of mineral nitrogen fertilisers (not allowed in organic farming) may reduce earthworms and competes with the cultivation of leguminous cover crops and green manures to increase the availability of nitrogen in soils, the latter being crops that are highly beneficial for earthworms. Lime seems to be beneficial to earthworm populations. In general, organic fertilisers (inclu-ding aerated slurry) have a far more positive impact on earthworms than mineral fertilisers.

Purely mineral fertilisation results in considerably lower numbers and biomass of earthworms compared to organic and, in a lesser degree, to combined mineral and organic (conventional) fertilisation. Results from the DOK long-term trial in Switzerland (average from 3 years).

Source

Lukas Pfiffner (FiBL), 2023, Earthworms – architects of fertile soils. Available on : https://www.fibl.org/fileadmin/documents/shop/1629-earthworms.pdf