Allelopathy

Allelopathy encompasses the biochemical interactions carried out by plants among themselves or with microorganisms.

Definition

The origin of the word comes from the Greek allelo ("each other") and pathos ("suffering", "affect"). Thus, this etymology implies that these interactions are negative: competition for resources, defense mechanisms. The current meaning of allelopathy also includes positive interactions, such as cooperation phenomena or stimulation of microorganisms. These interactions occur through compounds called allelochemicals, released by the plant into its environment. Most often, these compounds are secondary metabolites and belong to very diverse biochemical families[1].

Principles

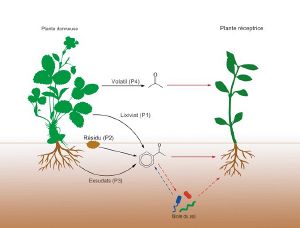

The chemical compounds involved in allelopathy can be released by three pathways in the plant:

- the roots (exudation)

- the aerial parts (leaching or volatilization)

- the decomposition of dead plant residues

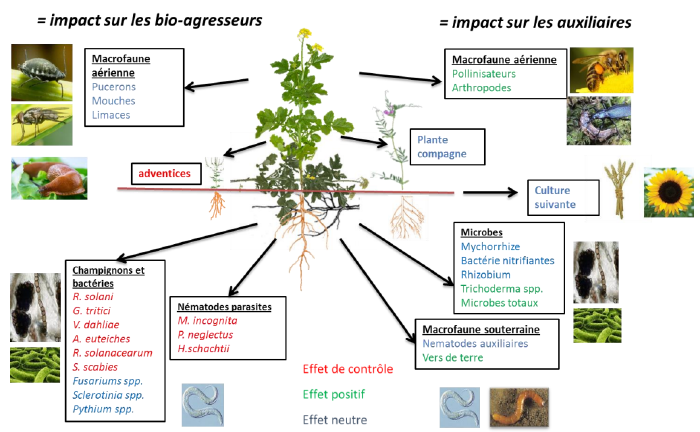

Allelopathy is mainly recognized for its interest in weed control in fields (inhibitory effect on weed growth). It is used in crop rotations, whether in intercrop with cover crops or in crop with mulch, or even through bioherbicides. From an agroecological crop management perspective, allelopathy is particularly interesting because it allows to limit weeding interventions, and sometimes also plays a role in pest and phytopathogen control (practice of biofumigation).

Allelochemical substances

By types

Allelochemical substances lead to interactions between individuals of different species; they are interspecific substances. We distinguish allomones, kairomones, and synomones[3].

- Allomones: An allomone is a substance produced by a living organism that interacts with another living organism of a different species, to the benefit of the emitting species.

- Kairomones: This is a substance produced by a living organism that interacts with another living organism of a different species, to the benefit of the receiving species.

- Synomones: A synomone is a substance produced by a living organism that interacts with another living organism of a different species, to the mutual benefit of both the emitting and receiving species.

By chemical families

Allelochemical molecules are mainly:

- phenolic acids, which can disrupt mineral absorption by the plant

- quinones, which can act on gene expression of target individuals

- terpenes, known to inhibit growth of certain plants by inactivating growth enzymes.

Examples of allelopathic plants

The walnut (Juglans nigra): it releases a substance called juglone, mainly from its roots, which inhibits the growth of many other plants, particularly tomato, potato crops, and some vegetables.

The eucalyptus (genus Eucalyptus): its leaves contain allelopathic essential oils which, upon decomposition, can limit germination of neighboring plants.

The rice: some rice varieties produce allelopathic substances that can prevent weed growth in rice paddies.

The garlic (Allium sativum): it releases allelopathic compounds that can inhibit certain unwanted weeds and limit soil diseases.

Applications in agriculture

Biofumigation and glucosinolates

Glucosinolates are sulfur-containing secondary carbohydrate metabolites mainly produced by plants of the order Capparales, which include crucifers (Brassicacea)[4].

Crucifers known for biofumigation[5]

- Brown mustard (Brassica juncea): it appears to have the most powerful allelopathic action. It contains high levels of active glucosinolates, producing volatile isothiocyanates (ITCs) with rapid action from aerial parts and roots. In vitro tests have shown the ability of brown mustard residues to inhibit mycelial growth of Aphanomyces euteiches, a pathogenic fungus of pea.

→ See the technical sheet Establishing allelopathic cover crops for more details on brown mustard and its field use.

- Rapeseed (Brassica napus): it is frequently cited for its "sanitizing" properties due to glucosinolates present in its seeds and vegetative parts. Its crop residues can contribute to biofumigation by releasing ITCs with rapid and slow action, derived from aerial parts and roots, respectively. However, at maturity, rapeseed vegetative parts contain very low concentrations of active glucosinolates.

- White mustard (Sinapis alba): it contains lower total glucosinolate concentrations than rapeseed and brown mustard, giving it less significant allelopathic potential. It produces less volatile ITCs than rapeseed, suggesting slower action. White mustard residues could slow mycelial growth of Aphanomyces euteiches.

- Black mustard (Brassica nigra): it is a crucifer potentially promising for an effect on wheat take-all, due to its glucosinolate composition.

Allelopathy of weeds on cultivated plants

- Wild oat (Avena fatua) significantly reduces leaf and root growth of wheat through its root exudates.

- Rough oat (Avena strigosa) has demonstrated a depressive effect on growth of various weeds, notably reducing biomass and coverage.

Allelopathy of cultivated plants on weeds

- Sunflower (Helianthus annuus) has strong allelopathic potential on many weeds, affecting germination and growth of white mustard (Leather, 1983)[6].

- Annual wormwood (Artemisia annua) produces artemisinin, a molecule with proven phytotoxic properties, which inhibits weed growth both in laboratory and field[7].

Allelopathy of cultivated plants on other cultivated plants

It can come from effects of crop residues on the surface or buried in soil, crop rotation, cultural practices, etc.

Alfalfa (Medicago saliva L.) is autotoxical and allelopathic; the height and fresh weight of alfalfa are lower on soil from an alfalfa field than on soil from a sorghum field. Allelochemical compounds in soil under alfalfa are involved in growth inhibition.

Aqueous extracts of decomposing rice (Oryza sativa) residues in soil inhibit radicle growth of lettuce.

Insecticidal effects

Devakumar and Parmar, (1993), discovered that more than 300 plants can reduce a large number of insects. In Morocco, Fahad et al., (2012) conducted a study on the insecticidal effect of root exudates of Mandragora autumnalis Bertol (mandrake) on Mediterranean fruit fly (Ceratitis capitata). High concentrations of aqueous and ethanolic extracts of mandrake roots (30g/20ml and 20g/ml) cause disturbances in the digestive system, resulting in abdominal swelling with blockage of excrement at the anus, leading to death of Ceratitis capitata[8].

Nematicidal effects

Crucifers (Brassicacea) are known to have nematicidal effects during their decomposition. This decomposition releases biocidal isothiocyanates which, under the action of the enzyme myrosinase, affect parasitic nematodes.

Limits

Although allelopathy presents promising potential for crop management, its large-scale application in agriculture faces several limitations.

- Under real conditions, it is extremely difficult to separate allelopathic effects from competition for resources[6]. The two phenomena interact and influence plant growth, making it difficult to isolate the specific impact of allelopathy.

- The diversity of allelochemical molecules produced, the concentration levels of these molecules depending on species and cultivars, and the sensitivity of pathogens to these molecules make prediction and generalization of allelopathic effects difficult[5].

- Environmental factors such as climate, soil type, and cultural practices strongly influence the expression of allelopathy. For example, soil texture, pH, organic matter, and nitrogen levels can affect retention and degradation of allelochemical compounds.

- Allelopathy is not limited to plant-plant interaction; it also involves soil microorganisms. Allelochemical compounds can affect not only targeted pathogens but also beneficial microorganisms, which can have unintended consequences on soil health[6]. It is essential to assess the overall impact of allelopathic practices on the soil ecosystem. Further research is needed to identify specific allelochemicals, their modes of action, persistence in soil, and impact on various soil organisms.

- ↑ C Aubertin, 2018, https://dicoagroecologie.fr/dictionnaire/allelopathie/

- ↑ Gfeller and Wirth, (2017)

- ↑ Académie de Montpellier [page consulted on 10/25/2024] https://tice.ac-montpellier.fr/ABCDORGA/Famille6/PHEROMONES.htm

- ↑ Biotic regulation potentials by allelopathy and biofumigation and disservices produced by multiservice cruciferous cover crops, L Alletto et al., 2018, https://draaf.nouvelle-aquitaine.agriculture.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/3rdf2018-actes-1_cle415433.pdf

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Another look at crop successions: Understanding and using allelopathy to improve crop management in rotation, R Reau et al., 2019, https://agroparistech.hal.science/hal-02314710/document

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Allelopathic effects of an oat cover and their impacts on soil macrofauna, Marie-Emilie EVENO, 2000, https://agritrop.cirad.fr/476940/1/ID476940.pdf

- ↑ Allelopathy: a controversial but promising phenomenon, J. WIRTH et al., Agroscope, 2012

- ↑ Allelopathy: use in Organic farming and its impact on the environment, K El assri et al., 2021, https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Hassnae-Azoughar-2/publication/372079580_L'allelopathie_utilisation_en_agriculture_biologique_et_son_impact_sur_l'environnement/links/64a3ffa58de7ed28ba744ff4/Lallelopathie-utilisation-en-agriculture-biologique-et-son-impact-sur-lenvironnement.pdf