Use Isaria fumosorosea to control insects, particularly whiteflies

Imagine a pest control solution that is not only effective, but harnesses the power of nature itself. Isaria fumosorosea, a remarkable fungus found in soils and plants worldwide, is helping farmers protect their crops from destructive insect pests in an environmentally friendly way. In this article, you will discover how this biological ally works, why it is beneficial for sustainable agriculture, and how growers can integrate it into modern pest management.

What is Isaria fumosorosea? A natural ally for pest control

Biology

Isaria fumosorosea is a fungus which lives mostly in the soil worldwide, but it is also found on plants and in water. This organism is an insect killer, or entomopathogen. The fungal colonies start out white and can change to a pink or purple color as they grow. The fungus has a basic, asexual life cycle. The infectious parts are called conidia and blastospores [1]

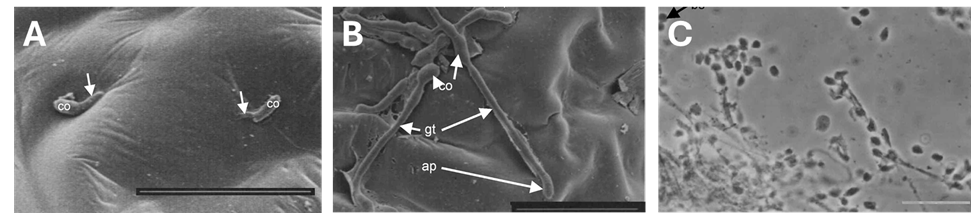

For the fungus to kill a pest, its spores must first stick firmly to the insect's outer skin (cuticle). It then produces special enzymes that help it break through the insect's protective layer [1][2]. The time required for an I. fumosorosea spore to penetrate the insect cuticle varies with the specific fungal strain and the host, but the critical breach is generally rapid. The spore first adheres, germinates, and uses enzymes (like those that suggest serious cuticular damage) to penetrate the insect's protective layer. For a highly virulent isolate (EH-506/3) tested against whitefly nymphs, significant cuticular damage was observed as early as 6 hours after inoculation [2]. Evidence of successful internal colonization, characterized by hyphal growth emerging from the host’s body, was documented starting at 12 hours for this fast-acting strain. Therefore, for susceptible hosts and effective isolates, the penetration phase is often completed within the first 12 to 24 hours, well before visible symptoms become widespread (which typically occurs within 24 to 48 hours)[2][3].

The high level of natural variation found in different strains means that I. fumosorosea is considered a species complex. For example, one virulent strain showed 92.6% mortality against Colorado potato beetle larvae, while the reference strain Apopka 97 showed 54.5%.[4]

Host range and crops

I. fumosorosea is highly valued in farming because it has a very broad host range, capable of infecting over 40 species of arthropods, including pests from at least 10 different insect orders. This makes it useful against many different agricultural pests. The pests it controls include whiteflies, aphids, mealybugs, thrips, psyllids (like the Asian citrus psyllid), and different types of beetles and caterpillars [6][3]. In France, the commercial product PREFERAL WG (containing strain Apopka 97, 109 UFC/g) is authorized as an insecticide, primarily for the control of whiteflies (Aleurodes), specifically under closed shelters [3]. Specific authorized crop uses in France/Europe for the control of Aleurodes include:

- Vegetables and fruits: Tomatoes and aubergines, cucurbits (with edible and non-edible skin), beans and peas (shelled and unshelled fresh), pepper, strawberry, blackcurrant, and raspberry.

- Ornamentals / other: Trees and shrubs, flowering and foliage plants, rose, aromatic herbs, and seed-bearing crops.

I. fumosorosea and whiteflies: A focused ally

I. fumosorosea is one of the most important natural enemies of whiteflies. Whiteflies, especially species like the sweet potato whitefly (Bemisia tabaci) and the greenhouse whitefly (Trialeurodes vaporariorum), are global concerns because they damage crops directly through feeding and indirectly by transmitting devastating viruses (like begomoviruses).[7][8]

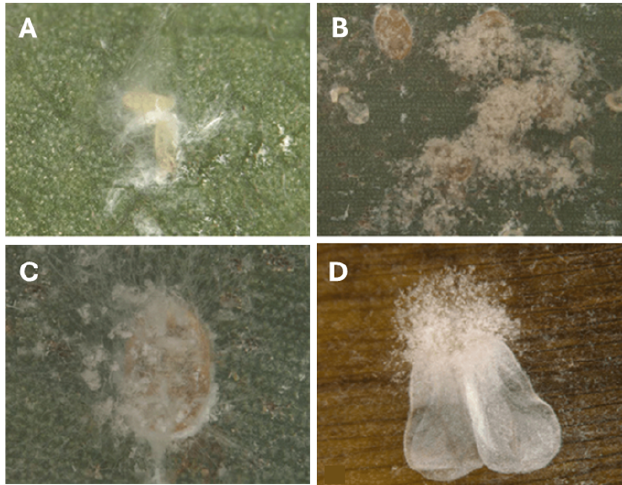

The fungus works by infecting the insect body. Its spores (blastospores or conidia) must stick to the insect's outer skin (cuticle). Once attached, the fungus produces structures that penetrate the cuticle, causing serious damage often attributed to enzymatic action. Once inside, the fungus multiplies and causes death. For farmers, this means seeing infected whiteflies, which often stop moving or appear moldy.[8][7][3]

Targeting whitefly life stages

I. fumosorosea can infect eggs, nymphs (immature stages), and adults of whiteflies. However, the immature stages (nymphs) are typically the most susceptible targets. When tested, different fungal isolates show variable speed of kill (virulence). For instance, some commercial strains have demonstrated a median lethal time (LT50) as low as 3.72 days against second instar B. tabaci nymphs, while other isolates took longer, up to 6.36 days. The fungus provides good control activity against whitefly nymphs on the leaf surface, but multiple applications are generally needed for successful control [7][3][9]

Why use isaria?

Farmers look for tools that are effective, safe, and sustainable. I. fumosorosea excels in these areas, especially when compared to traditional chemical control:

- Safety and low risk: I. fumosorosea is considered a low-risk environmental alternative to chemical insecticides. It is safe for workers; for example, acute dermal toxicity tests showed no inflammatory reactions or clinical signs of disease, supporting its safety when applied to the skin. It poses a negligible risk to birds and mammals, particularly since its representative uses focus on glasshouse application.[10][3]

- No resistance development: Unlike synthetic chemicals, which face widespread pest resistance (making them less effective over time), studies on B. tabaci exposed to I. fumosorosea over multiple generations showed no significant differences in susceptibility. This means the product can be relied upon long-term without resistance issues.[7][11]

- Compatibility with biocontrol: The fungus is vital for Integrated Pest Management (IPM) programs. It is compatible with many beneficial natural enemies used in greenhouses, such as the parasitoid Encarsia formosa, predatory mites, and bugs like Macrolophus caliginosus. [3][7]

- Synergy with combined treatment: While Isaria acts slower than chemical sprays (often taking 7–10 days to cause death), its speed and efficacy can be significantly boosted when combined with certain chemical insecticides. Strong synergistic actions have been observed in mixtures of I. fumosorosea with insecticides like Spirotetramat, Imidacloprid, and Thiamethoxam during the first 2–4 days after treatment. This joint action helps to shorten the time it takes for the pest to die. It is also highly compatible with insect growth regulators (IGRs) like Buprofezin, which can act as an effective adjuvant for whitefly control.[7][3][8]

When to use isaria (strategy and timing)

Applications should target the first whitefly larvae. Repeated treatments (often 2 to 3 treatments) spaced by a minimum interval (e.g., 15 days) are typically needed, especially against whitefly nymphs.[3][12]

- Application timing: Apply Isaria products, often formulated as Water Dispersible Granules (WG), in the late afternoon or evening, or on cloudy/rainy days. This timing protects the spores from UV rays and ensures a period of naturally higher humidity, maximizing the chances of spore germination. [3][13][12]

How to use isaria and when: crucial field considerations

For I. fumosorosea to work effectively, careful application timing and environmental management are critical. To maximize the effect and overcome environmental limitations, follow these best practices:

Application method:

Spray to glisten, not to runoff. The product is often applied as a "spot treatment" to areas with high pest density, especially in greenhouse settings. In the case of Preferal WG must be prepared through a preliminary mixing step in clean water with gentle agitation before being added to the spray tank. The mixture should be prepared immediately before application to ensure the viability of the fungal spores and to avoid sedimentation. During spraying, continuous agitation is essential to maintain a homogeneous suspension.[3][12]

In contrast to PFR-97, which requires prolonged mixing and uses only the supernatant after sedimentation, Preferal WG should neither be left to settle nor filtered prior to use. However, because its suspensions have limited stability, operator experience and careful handling—particularly maintaining consistent agitation—are key factors to optimize product performance.[3][14]

No complex pre-processing steps are required beyond proper mixing and tank management. It is also important to avoid combinations with incompatible products that could affect fungal viability.

- Tank mixing and compatibility: If tank mixing with chemical products, ensure compatibility. Some fungicides, especially those containing copper or the product Bellis (at high concentrations like 100 mg/L), can inhibit fungal growth and should be avoided.

Environmental considerations

The fungus is a living organism, and its survival and ability to infect depend heavily on the conditions immediately after application:

- Humidity is key: The most crucial factor for initiating infection is high relative humidity (RH). The fungus requires RH above 95% for a short period so the spores can properly germinate and penetrate the insect’s protective cuticle. [3]

- Temperature range: Fungal growth is successful within a temperature range, with optimal colony growth occurring between 23°C and 25°C. Growth slows above 25°C and stops completely above 32°C. In field trials, even when average temperatures (e.g., 22 °C–26 °C) seem conducive, the mortality rate can be lower than in the lab due to other limiting factors.[14]

- UV radiation (sunlight): The spores are highly sensitive to sunlight. UV-B radiation is the most detrimental factor and can rapidly reduce spore viability. This is a major reason why field mortality is often lower than lab results.[14][15]

- Wind and coverage: While not as direct a killer as UV, efficacy can be reduced if the application does not reach the pests, particularly because whiteflies often reside on the lower leaf surface, requiring thorough spray coverage (avoiding lack of translaminar coverage).[14][12]

- ·Other reductions in efficacy: Fungal efficacy can be reduced by factors like rainfall washing blastospores off the plants or the biodegradation of spores over time.[14][16]

Storage and preparation:

Spores are living. They are harmed by high temperatures and should be stored in the fridge (2–6°C) to achieve maximum shelf life (e.g., 6 months). Do not keep the spores submerged in water for more than 24 hours prior to spraying.[3] [4] Continuous agitation in the spray tank may be necessary to keep the product properly suspended. Always wear appropriate protective equipment, such as a mask and gloves, during mixing and application.[12][3]

Compatibility with chemical products and biocontrol strategies

I. fumosorosea is an important component of Integrated Pest Management (IPM) programs. It is generally considered compatible with many beneficial biological control agents used in greenhouses, such as the parasitoid Encarsia formosa and various predatory mites and insects like Delphastus and Dicyphus. Using Isaria helps preserve these natural enemies.[7][12]

Mixing Isaria with certain chemical insecticides can be highly effective. This combined approach often shows a synergistic effect, meaning the combined result is better than using either product alone. For example, mixing the fungus with Thiamethoxam or Imidacloprid can boost the immediate control rate against whiteflies. Similarly, testing showed that mixing Isaria with the insect growth regulator Buprofezin produced excellent results against invasive whiteflies.[14][7][8]

However, care is needed when mixing with fungicides. While some fungicides (like Carbendazim and Ridomil Gold) are compatible with Isaria at normal rates, others, such as certain copper-based products or high concentrations of products like Bellis, can inhibit the growth of the fungus and should be avoided in tank mixes. Always check the compatibility information before tank mixing. [17][18]

Some considerations

Effects on Beneficial Arthropods and Pollinators

Isaria fumosorosea is generally compatible with many natural enemies, including parasitoids and predators, making it suitable for IPM programs. However, there is a moderate caution for bees due to potential contact exposure. Because available data are limited, growers should apply basic mitigation measures[3][19]:

- Avoid spraying during flowering.

- Apply in the evening or at night in pollinator-dependent crops.

These practices help minimize risk when regulatory information for pollinators is incomplete.

Safety for Vertebrates and Mammals

Regulatory evaluations indicate a low risk for mammals and birds. No unusual toxic or pathogenic characteristics have been observed. In greenhouse uses, additional toxicity data are often waived due to minimal exposure. Overall, I. fumosorosea is considered safe for wildlife.

Aquatic Environment and Persistence

The fungus can persist in soil and water, similar to other entomopathogenic fungi, but it is not considered a hazard to aquatic organisms. One key characteristic is its heat sensitivity: temperatures above 25 °C sharply reduce viability.

This has two implications:

- It lowers the risk of residues in harvested food (since processing temperatures inactivate it).

- ·Growers must maintain cool, stable storage conditions to preserve product effectiveness.

Human Health and Worker Exposure

The main human-health concern is not toxicity, but the risk of sensitization or allergy from repeated exposure to spores. Therefore, applicators must use full PPE, including protective clothing, gloves, eye protection, and—critically—a NIOSH-approved respirator for particulates.[3]

Although biologicals reduce chemical exposure, proper respiratory protection remains essential to avoid inhalation of spores during handling and application.

Secondary Metabolites (Mycotoxins)

Like other fungi, I. fumosorosea produces secondary metabolites, some potentially toxic. Current evidence suggests a very low likelihood of these compounds entering the food chain. Its heat sensitivity further reduces residue risk. Still, this is an area where ongoing research is recommended.

Effects on Soil Microorganisms and Biocontrol Agents

Spores can enter the soil through drift or infected cadavers, but no negative environmental or human-health impacts from soil entomopathogenic fungi have been reported.

Interactions with other biocontrol agents, especially entomopathogenic nematodes (EPNs), can be significant:

- Simultaneous application of I. fumosorosea and EPNs can improve pest control.

- Applying nematodes more than 24 hours later may reduce nematode performance due to inhibitory bacterial metabolites.

Thus, timing is critical when combining both tools in integrated control programs.

Key Operational Limitations for Growers

- Slow speed of action: The fungus takes 2–5 days to kill pests. Under high pest pressure, it may appear less effective than chemicals. This means growers should use it preventively rather than as a crisis treatment.

- Storage and stability: Viability drops quickly above 25 °C, making proper storage essential. Poor temperature management leads directly to control failure.

- Tank-mix compatibility and crop interactions: While compatible with many products, it should not be mixed with botanical oils, borax, or some copper fungicides, which can inhibit fungal growth.

- In some crops, natural plant chemicals may also reduce efficacy, so small preliminary tests are recommended before full adoption in new crop–pest systems.

Conclusion

I. fumosorosea is a powerful tool for pest control, particularly against whiteflies, offering a sustainable alternative that is safe for workers, preserves beneficial insects, and avoids the serious problem of insecticide resistance. While it relies heavily on favorable environmental conditions (high humidity, moderate temperature, and low UV exposure), these requirements can be managed through careful application timing (evening sprays) and compatible formulations. Combining Isaria with chemical partners, especially IGRs or certain insecticides (like Imidacloprid or Thiamethoxam), can achieve faster and more robust control results than the fungus used alone.

Perspectives

- Embrace combined strategies: Do not rely solely on the fungus for rapid control. Incorporate Isaria alongside beneficial insects and consider tank-mixing with compatible chemicals (especially IGRs) to manage infestations effectively and quickly. This approach reduces the overall chemical load and environmental impact.

- Timing is everything: Recognize that this product is highly biological. Treat it like a living organism. Maximize efficacy by ensuring the microclimate immediately following application is favorable (high humidity, protection from sun).

- Future - proof your farm: Because whiteflies cannot easily develop resistance to Isaria, incorporating it into your routine pest control schedule is a long-term strategy that helps protect the few effective chemical tools you still have access to.

- Monitor compatibility: If you need to use fungicides, always check the compatibility data or contact a specialist. Products like Carbendazim and Ridomil Gold appear safe to use, but others like certain high-concentration copper-based products or Bellis should be avoided or applied separately by several days.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Brunner-Mendoza, C., Navarro-Barranco, H., León-Mancilla, B., Pérez-Torres, A., & Toriello, C. (2017). Biosafety of an entomopathogenic fungus Isaria fumosorosea in an acute dermal test in rabbits. Cutaneous and Ocular Toxicology, 36(1), 12–18. https://doi.org/10.3109/15569527.2016.1156122

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Castellanos-Moguel, J., Mier, T., Reyes-Montes, M. del R., Navarro Barranco, H., Zepeda Rodríguez, A., Pérez-Torres, A., & Toriello, C. (2013). Fungal growth development index and ultrastructural study of whiteflies infected by three Isaria fumosorosea isolates of different pathogenicity. Revista Mexicana de Micología, 38, 55–61

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 Belgium. (2013). Isaria fumosoroseusa strain Apopka 97 Volume 1 – Report and Proposed Decision May 2013 (Draft Assessment Report).

- ↑ Hussein, H. M., Skoková, O., Půža, V., & Zemek, R. (2016). Laboratory Evaluation of Isaria fumosorosea CCM 8367 and Steinernema feltiae Ustinov against Immature Stages of the Colorado Potato Beetle. PLoS ONE, 11(3), e0152399.

- ↑ GÖKÇE, A., & ER, M. (2005). Pathogenicity of Paecilomyces spp. To the Glasshouse Whitefly, Trialeurodes vaporariorum, with Some Observations on the Fungal Infection Process. Turkish Journal of Agriculture and Forestry, 29(5), 331–340. https://doi.org/-

- ↑ Arthurs, S. P., Aristizábal, L. F., & Avery, P. B. (2013). Evaluation of entomopathogenic fungi against chilli thrips, Scirtothrips dorsalis. Journal of Insect Science, 13

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 Sani, I. (2020). A review of the biology and control of whitefly, Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae), with special reference to biological control using entomopathogenic fungi. Insects, 11(9), 619

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Zou C., Li L., Dong T., Zhang B., & Hu Q. (2014). Joint action of the entomopathogenic fungus Isaria fumosorosea and four chemical insecticides against the whitefly Bemisia tabaci. Biocontrol Science and Technology, 24(3), 315–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/09583157.2013.860427

- ↑ Ruiz-Sánchez E., Munguía-Rosales R., & Torres-Acosta R. I. (2013). Virulence and genetic variability of Isaria fumosorosea isolates from the Yucatan Peninsula against Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae). International Journal of Agricultural Science, 3(2), 113-118.

- ↑ Brunner-Mendoza, C., Navarro-Barranco, H., León-Mancilla, B., Pérez-Torres, A., & Toriello, C. (2016). Biosafety of an entomopathogenic fungus Isaria fumosorosea in an acute dermal test in rabbits. Cutaneous and Ocular Toxicology. https://doi.org/10.3109/15569527.2016.1156122.

- ↑ Gao, T., Wang, Z., Huang, Y., Keyhani, N. O., & Huang, Z. (2017). Lack of resistance development in Bemisia tabaci to Isaria fumosorosea after multiple generations of selection. Scientific Reports, 7, 42727

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 UConn. (2023). Entomopathogenic Fungi for Greenhouse Pest Management. UConn Extension IPM Program.

- ↑ Sandeep, A., Selvaraj, K., Kalleshwaraswamy, C. M., Hanumanthaswamy, B. C., & Mallikarjuna, H. B. (2022). Field efficacy of Isaria fumosorosea alone and in combination with insecticides against Aleurodicus rugioperculatus on coconut. Egyptian Journal of Biological Pest Control, 32, 106. https://doi.org/1186/s41938-022-00600-z.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 Kumar, V., Francis, A., Avery, P., McKenzie, C., & Osborne, L. (2018). Assessing compatibility of Isaria fumosorosea and buprofezin for mitigation of Aleurodicus rugioperculatus (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae)—An invasive pest in the Florida landscape. Journal of Economic Entomology, 111(3), 1069–1079.

- ↑ Loong, C., Ahmad, S. S., Hafidzi, M. N., Dzolkifli, O., & Faizah, A. (2013). Effect of UV-B and solar radiation on the efficacy of Isaria fumosorosea and Metarhizium anisopliae (Deuteromycetes: Hyphomycetes) for controlling bagworm, Pterona pendula (Lepidoptera: Psychidae). Journal of Entomology, 10, 53–65

- ↑ Loong, C., Ahmad, S. S., Hafidzi, M. N., Dzolkifli, O., & Faizah, A. (2013). Effect of UV-B and solar radiation on the efficacy of Isaria fumosorosea and Metarhizium anisopliae (Deuteromycetes: Hyphomycetes) for controlling bagworm, Pterona pendula (Lepidoptera: Psychidae). Journal of Entomology, 10, 53–65

- ↑ Khan, F. Z., Khan, A., Saravanakumar, D., & Thomas, A. (2024). In vitro compatibility of Isaria fumosorosea from Bemisia tabaci with four commonly used fungicides in vegetable production. Journal of Advanced Studies in Agricultural, Biological and Environmental Sciences, 11(1), 1–11

- ↑ Avery, P. B., Pick, D. A., Aristizábal, L. F., Kerrigan, J., Powell, C. A., Rogers, M. E., & Arthurs, S. P. (2013). Compatibility of Isaria fumosorosea (Hypocreales: Cordycipitaceae) Blastospores with Agricultural Chemicals Used for Management of the Asian Citrus Psyllid, Diaphorina citri (Hemiptera: Liviidae). Insects, 4(4), 694–711. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects4040694. [73, 76–84, 87]

- ↑ EFSA (European Food Safety Authority). (2014). Conclusion on the peer review of the pesticide risk assessment of the active substance Isaria fumosorosea strain Apopka 97. EFSA Journal, 12(5), 3679. [63–67, 122–125]