Managing Deficiencies in Field Crops

A deficiency is the absence or insufficient presence or a lack of assimilability of an element essential to a plant's life.

The main cause of a deficiency can be masked by disorders related to climate, agronomy, or nutritional imbalances. Symptoms can also vary depending on varieties. Therefore, it is important to ensure that all possibilities have been considered before making a decision to restore crop health.

To assess a deficiency situation, the sensitivity of crops must be cross-referenced with soil, vegetation, or climate conditions and the fertilization history.

Description

Along with diseases, deficiencies often signify a imbalance. When deficiency symptoms are visible, the plant's under-nutrition state is already advanced. In this case, it is appropriate to apply an anti-deficiency treatment, either foliar or soil-applied.

There are two types of deficiencies: true and induced deficiencies. In both cases, a deficiency directly impacts yield and crop quality.

True deficiencies

They result from a deficiency of a nutrient element in the soil, which is therefore not available to the plant.

Induced deficiencies

In this case, nutrient elements are available but their assimilation by the plant is impossible. They are often due to physico-chemical characteristics of the soil: pH, soil structure or soil textures, organic matter content, imbalance between elements, antagonisms, or certain climatic conditions (cold, humidity, excess water).

Examples:

- High pH can induce a phytodisponibility problem of manganese.

- A blown soil can induce manganese deficiency or zinc deficiency if it is too compacted.

- Organic matter content can affect the availability of copper and manganese.

- Cold favors the appearance of zinc deficiency symptoms on corn.

The most frequently observed deficiencies (zinc, manganese) are often induced[1].

Major elements

Nitrogen

Nitrogen is one of the main nutrient elements in terms of quantity and plays a key role in the general metabolism of plants. Nitrogen is essential for the crop to allow strong vegetative growth and to synthesize chlorophyll which provides energy to the plant. It is also essential in the formation of proteins. A blockage of assimilation, especially at the end of the cycle during dry periods, can quickly lead to a decrease in yield and production quality.

During nitrogen deficiency, the plant organs are smaller than usual, and the yield is significantly affected. Since nitrogen plays a crucial role in protein production, contents can also be lower, implying lower quality at harvest.

Phosphorus

Phosphorus, like nitrogen, plays an important role in the formation of proteins. This element is key in the plant's energy metabolism, so sugar and protein transport and production are impacted in case of deficiency. Phosphorus allows the plant to develop its root system. It also plays a role in flowering and fertilization of the crop.

Generally, when phosphorus is lacking, root growth slows down, and tillering (in the case of cereals) is also affected. As with nitrogen deficiency, flowering is delayed, and protein production is limited.

Potassium

Potassium plays a crucial role at the cellular level, makes the cell wall thicker, and also regulates plant transpiration as well as lodging risks. It also makes the plant more resistant to frost and drought.

Dry matter is specifically impacted by potassium deficiency and is restricted. If potassium deficiency is harmful, excess is also harmful and promotes the appearance of fungi.

It is poorly mobile in the soil. The amount dissolved in immediately available water remains low, and roots must explore the soil to find sufficient quantities of these elements.

Secondary elements

Sulfur

Sulfur is essential in the production of proteins, amino acids, and certain vitamins in the plant. Moreover, it also plays a role in the reduction of nitrates into amino acids. Unlike yield, the quality of the harvest largely depends on soil sulfur availability.

Calcium

Calcium is crucial during the growth of new cell tissues, notably the wall which it stiffens. Therefore, it ensures good mechanical resistance of the plant. It also participates in metabolism and the formation of the cell nucleus. When production is relatively low, quality must be prioritized, and calcium plays an even more important role. Indeed, good calcium nutrition provides the plant with a natural resistance to mold by preserving cell integrity during transport and storage. Calcium also promotes young root growth in synergy with other elements.

In case of deficiency, the plant shows limited growth and is much more fragile to mechanical hazards that may occur (fauna, weather…).

Magnesium

Magnesium plays a crucial role in plant growth because it directly affects the synthesis, transport, and storage of sugars. Magnesium is a central component of chlorophyll. It plays a role in catalyzing photosynthesis. Furthermore, magnesium prevents aluminum toxicity by participating in the synthesis of protective organic acids that limit the toxic effects of aluminum. It is also a component of pectins and phytins which have a structural role in the walls of plant cells. Needs range from 20 to 50 kg/ha of MgO depending on species. Protein synthesis is directly impacted by magnesium deficiency. Indeed, carbohydrate production is reduced, and amide concentration increases in leaves. However, the yield loss remains limited, rarely exceeding 15%.

Minor elements or trace elements

Trace elements, formerly called minor elements, are nutrient elements present in small quantities in the soil and absorbed in small quantities by plants. Numerous studies have shown their importance in plant functioning: cell respiration (iron, copper), photosynthesis (iron, copper, and manganese), protein synthesis (iron, zinc), and hormones (zinc, boron), nitrogen absorption (iron, copper, molybdenum)…

Trace elements that can cause problems in field crops are iron (Fe), manganese (Mn), zinc (Zn), copper (Cu), boron (B), and molybdenum (Mo). Cereal straw crops are particularly demanding in copper and manganese, and corn in zinc and manganese.

The effects of trace element deficiencies can be highly detrimental to crops. Therefore, they are sometimes necessary fertilizers and, based on well-developed diagnostic tools, can be considered when establishing fertilization plans.

Copper

Copper plays an important role in the plant in cell respiration, photosynthesis, and nitrogen absorption.

A soil rich in limestone and organic matter will be more exposed to copper deficiency. In case of copper deficiency, sterility of ears can quickly appear.

Crops very sensitive to deficiency: Wheat, barley, oats.

Crops sensitive to deficiency: Corn, sorghum, pea, alfalfa[2].

Manganese

Manganese is involved in photosynthesis and chlorophyll production. It helps activate enzymes involved in distributing growth regulators in the plant.

Crops very sensitive to deficiency: Wheat, barley, oats, sorghum, pea, soybean.

Crops sensitive to deficiency: Corn, alfalfa, rapeseed, sunflower, clover.

Zinc

Zinc is important in the early stages of growth and in seed formation. It plays a role in the production of chlorophyll and carbohydrates. It is also essential for the synthesis of proteins and plant hormones.

Crops very sensitive to deficiency: Corn, flax, bean.

Crops sensitive to deficiency: Sorghum, soybean.

Iron

Iron is necessary for chlorophyll formation, plant respiration, and the formation of certain proteins. It also plays a role in nitrogen absorption.

Crops very sensitive to deficiency: Pea, soybean.

Crops sensitive to deficiency: Corn, sorghum, lupin, beans.

Boron

Boron plays an important role in cell wall structure, fruit set and seed formation as well as in protein and carbohydrate metabolism. Boron is also essential for proper hormonal functioning of plants.

Crops very sensitive to deficiency: alfalfa, sunflower.

Crops sensitive to deficiency: rapeseed, pea, flax, clover, vine.

Molybdenum

Molybdenum contributes to good nitrogen absorption in the plant.

Crops very sensitive to deficiency: Alfalfa, pea, clover.

Crops sensitive to deficiency: Rapeseed, soybean.

Table of threshold values for each element in the soil

The table below summarizes the main comfort threshold values of elements in the soil. If one of the values is in red for any element, intervention is required as it may indicate a non-functional soil.

| Trace element name | Low threshold | Comfort zone | High threshold |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cu | < 0.5 ppm | 2-50 ppm | > 150 ppm |

| Mn | < 15 ppm | 35-250 ppm | > 350 ppm |

| Zn | < 1 ppm | 4-300 ppm | > 300 ppm |

| S | < 6 ppm | < 15 ppm | > 250 ppm |

| Na/CEC | < 0.3 % | 0.5-5 % | > 6 % |

| K2O | < 60 ppm | > 80 ppm | - |

| K/CEC | < 1.5% | 2-7% | > 10% |

| P2O5 Dyer | < 70 ppm | 100 ppm | > 150 ppm |

| P205 J. Hebert | < 60 ppm | 80 ppm | > 120 ppm |

| P2O5 Olsen | <30 ppm | 40 ppm | > 60 ppm |

| MgO | < 50 ppm | > 80 ppm | - |

| Mg/CEC | < 6% | 10-15% | > 18% |

| CaO | < 500 ppm | 1000-8000 ppm | > 10000 ppm |

| Ca/CEC | < 40% | 50-75% | > 80% |

| CEC | > 50% | < 30% | - |

| Cl- | < 10 ppm | 20-1000 ppm | > 2000 ppm |

| pH Water | ≤ 5.4 | 5.8-7.2 | > 7.8 ppm |

| Co | < 0.3 ppm | 0.5 ppm | > 2 ppm |

| Mo | < 0.2 ppm | 0.5 ppm | > 4 ppm |

| Boron | < 0.3 ppm | 0.5 ppm | > 4 ppm |

| Fe | < 25 ppm | 70 ppm | > 800 ppm |

Identifying deficiencies

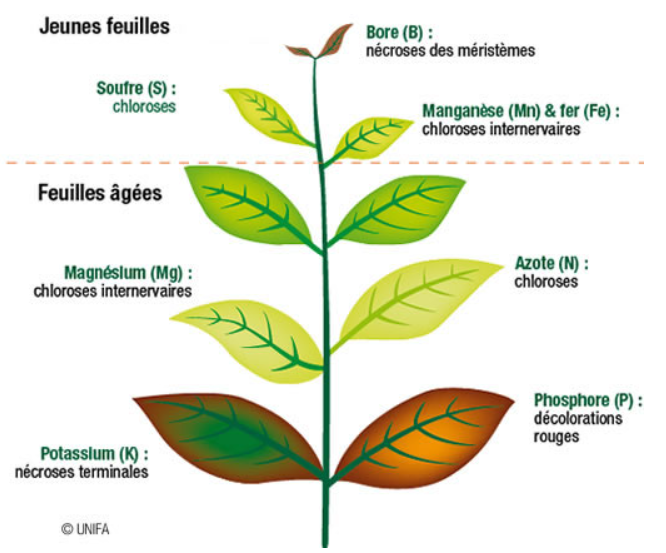

Deficient plants show characteristic symptoms such as chlorosis, deformations, or necrosis of organs which must be observed methodically:

- Symptom location in the field and observation of the plant development stage : Deficiencies generally manifest as symptoms in patches or irregular spots of varying size, distributed randomly in the field. However, for some deficiencies like manganese, symptoms may be linked to cultural practices (wheel tracks). However, symptom distribution in patches is not specific to deficiencies. It can also be due to pests, for example. Conversely, if symptoms affect the entire field, it is more likely a climatic accident or phytotoxicity. In this case, it is necessary to analyze the climate of the previous days and list the last phytosanitary products used in the field to determine the cause of the symptoms.

- Know the soil-related risk factors : Poor root development linked to degraded structure by compaction can induce or reinforce a deficiency due to the plant's reduced absorption capacity for nutrients. Redox conditions related to soil aeration also influence the availability of certain trace elements like manganese. For example, manganese deficiency can be due to overly aerated soil where it is in its oxidized form. In this form, manganese is very poorly soluble and thus unavailable to plants. Therefore, to perform a complete deficiency diagnosis, it is essential to carry out a quick crop profile on affected and healthy areas.

- Soil water status, rooting profile : Heavy winter rains promote leaching of nitrogen and sulfur. Without adequate fertilization, sulfur and/or nitrogen deficiencies may occur.

- Affected parts on the plant : Before concluding a deficiency, examine the plant's health status. The symptoms observed may be related to attacks by pests or diseases. If the deficiency hypothesis is confirmed, it is necessary to determine the nutrient element involved. For this, a precise observation of the affected organs and the nature of the symptoms is required.

- Fertilization history : Knowing the technical itinerary and crop history of the field to identify possible interactions between elements.

Foliar or plant analysis requires interpretation considering the plant's development stage. It is often useful to combine it with soil analysis to confirm the diagnosis.

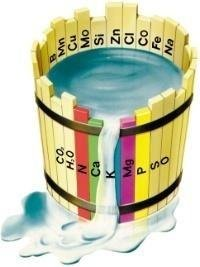

The law of limiting factors, established by Liebig in 1850, is one of the most important principles in agronomy. This theory on the mineral nutrition of plants states that the production level of a crop is set by the most limiting nutrient element. In other words, the yield of a crop is limited by the nutrient element that runs out first, regardless of the fertilization level of other elements. Trace elements are no exception. Trace element inputs should therefore not be automatic but considered after diagnosing limiting factors[3].

Liebig's law is commonly illustrated by a barrel or bucket where each stave represents the availability of nutrient elements, and the water level represents crop yield. The water level in the barrel is set by the shortest stave (the limiting factor), regardless of the height of the other staves.

Nitrogen

Symptoms

Nitrogen deficiency can manifest at all stages of plant growth and development.

The first signs of nitrogen deficiency generally appear on old leaves. These yellow progressively as nitrogen moves to younger, more productive leaves. This yellowing, for corn, occurs along the central vein, in a V shape, with the point toward the stem. Plants are also smaller.

In severe cases, leaves eventually necrose.

Diagnosis confirmation

- Nitrogen nutrition diagnostic tools (Jubil, N-tester…) allow detection of nitrogen deficiencies. However, these two tools cannot be used before flowering.

- Foliar diagnosis at flowering (less precise).

Risk Situations

- Nitrogen availability too low due to:

- Too low input.

- Leaching beyond root reach of part of the nitrogen applied.

- Limited rooting: competition with weeds and especially grasses.

- Water deficit: nitrogen deficiency caused by soil drying.

- Sandy soils, poor in humus.

Impact on yield

On fertilized plots, nitrogen deficiencies remain moderate and their impact on yield is low.

Phosphorus

Symptoms

Symptoms appear in patches during tillering.

A reddening or yellowing of the tip of old leaves and reduction of tillering are observed.

A severe deficiency can cause the withering of leaf tips.

Diagnosis confirmation

- Soil: Soil analysis allows detection of phosphorus deficiency. COMIFER proposes threshold contents for managing phosphate fertilization.

- Plant: At ear or flowering stage, deficiency thresholds for phosphorus content.

Risk Situations

- Wet and waterlogged soils.

- Phosphorus-poor soils.

- Old grasslands turned over and never fertilized.

Impact on yield

In wheat, damage generally does not exceed 10% rarely. In the most severe cases, yield loss can reach 20%.

Potassium

Symptoms

Symptoms can appear as early as the 4-leaf stage.

- In patches, reduction in size and yellowing of plants

- Very high heterogeneity in plant size

- Yellowing then browning and drying of the leaf blade tip, then leaf edges

- Symptoms first affect the oldest leaves. Young leaves may remain green if deficiency is mild.

- In severe deficiency, plants may disappear.

Diagnosis confirmation

- Soil: Soil analysis is a good indicator of potassium availability in the soil. Thresholds for potassium fertilization are established by COMIFER.

- Plant: Foliar diagnosis at female flowering. Interpretation is easier by comparing K contents of healthy and affected plants (Cost about €15/analysis).

Risk Situations

- Soils with low potassium availability

- Turning over old unmanaged grasslands

- Previous crops where all aerial parts are exported.

Evolution, impact on yield

In case of severe uncorrected deficiency, production can be strongly penalized or even null.

Sulfur

Symptoms

Symptoms appear from end of tillering to beginning of stem elongation. They will intensify until the last leaf stage.

At the field scale, deficiency-affected zones are distributed in patches, sometimes in strips, corresponding to overlapping passes for nitrogen spreading. Indeed, zones over-fertilized with nitrogen will be the first to show deficiency symptoms.

At the plant level, a reduced growth and reduced tillering can be observed in deficient plants. Internodes will also be shorter.

Young leaves will have a pale green appearance especially on the blade. Yellow or light green stripes may also appear along the veins.

However, be cautious as symptoms are not always visible.

Diagnosis confirmation

Diagnosis confirmation must be done by plant analysis. Sulfur content must be measured as a percentage of dry matter.

- At 1 cm ear stage, the N/S ratio seems more important than sulfur content. The plant is deficient if the ratio N/S > 12 to 15.

- At flowering, content is measured on the 2nd or 3rd leaf below the ear. Normal content is around 0.25 - 0.30%. The plant is deficient if content is below 0.20%.

- At two nodes, diagnosis can be established from sulfate concentration in the basal stem juice. Deficiency threshold is 200 mg/L.

- It is easier to diagnose deficiency by comparing these indicators with those of a healthy plant.

Risk Situations

- Sulfur is sensitive to leaching and dependent on mineralization. Thus, superficial clay-limestone soils, sandy soils and silty soils poor in organic matter are risk situations.

- In plots receiving regular organic inputs for at least 15 years, remaining supplies are usually sufficient to cover needs. In other situations, risk should be assessed to decide on the relevance of an input and determine its dose.

- High nitrogen inputs exacerbate sulfur deficiency.

Impact on yield

Sulfur deficiencies reduce the number of ears per m² and their fertility. Losses generally range from 2 to 10 q/ha. In severe deficiencies, losses can reach 20 q/ha.

Impact remains low if deficiency is corrected before the 2-node stage.

Calcium

Roots are the first victims of calcium deficiency: main roots do not develop properly, favoring small lateral roots.

Calcium moves little and slowly within the plant. Visual deficiency symptoms will therefore be localized. Yellowish/brown spots can be observed on leaves, especially on young leaves which are affected first.

In case of severe deficiency, flowering is compromised and leaf buds appear burnt and die. Fruits may be stunted and seeds have a lower germination rate.

Magnesium

Symptoms

Symptoms appear during tillering. They are symptoms of chlorosis.

At the field level, irregular, lighter patches with reduced growth can already be observed.

Magnesium notably moves towards younger leaves. Deficiency will cause yellowing of the oldest leaves first, then progressively younger leaves. Yellowing starts from leaf tips. Tissue between veins yellows but veins remain green. Severe deficiency can cause leaf margin curling. In severe cases, leaves may become red.

Diagnosis confirmation

- Soil: Soil analysis is a good indicator of potassium availability in the soil. Thresholds for potassium fertilization are established by COMIFER.

- Plant: Foliar diagnosis at 1 cm ear stage or flowering.

Risk Situations

- Silty soils more or less sandy: deficiency is aggravated by acidic and/or compacted soils.

- Sandy soils

- Certain calcareous soils due to low magnesium content in the parent rock.

Evolution, impact on yield

Yield losses due to magnesium deficiency rarely exceed 15%.

Copper

Symptoms

Symptoms appear in patches from end of stem elongation. Thus, plots are never entirely affected. In copper deficiency, ear sterility can quickly appear. At stem elongation, symptoms are:

- Constriction and curling of the last leaf tip

- White discoloration and drying of leaf tips: white tip symptom

At heading, one may observe:

- Deformed ears

- Sterile spikelets

- Difficulty of ears to emerge

- Plants remain green

- Grainless ears covered with 0, black fungi

- Sterile plants sometimes regrow from the base emitting 2 to 3 tillers

Diagnosis confirmation

Soil analysis is the most relevant to confirm deficiency. Diagnosis is based on Cu (mg/kg) / OM (%) ratio. Deficiency thresholds:

Risk Situations

- Soils with high OM content

- Soils with high pH (>7): recent liming or calcareous soils

- Very sandy soils

- High inputs of nitrogen and phosphorus

Manganese

Symptoms

Generally, symptoms appear at beginning of stem elongation. In severe cases, they can appear as early as the 3-leaf stage. Symptoms are observed at different scales:

- At the field:

- Irregular patches or strips linked to soil work and/or wheel passes

- Blown soil zones are most affected

- At the plant scale:

- Drooping, wilted, soft posture. Plants collapse to the ground.

- On the leaf:

- White to beige drying on young leaves, aligned between veins. (Most severe cases)

- Old leaves are affected first and often entirely dried.

- In very severe deficiency, all leaves are affected and plants may disappear.

Diagnosis confirmation

Soil analysis is unreliable. Prefer plant analysis. The simplest is to compare Mn contents between healthy and affected plants.

Risk Situations

- Very aerated, blown soils

- Soils rich in OM (>4%) or having received massive organic inputs

- Acid soils where pH has been raised too much by liming

Impact on yield

In the most severe cases, the crop can be destroyed in the most affected patches.

Zinc

Symptoms

In maize, symptoms can appear from 5 leaves up to 10-12 leaves. Observed symptoms:

- Whitish appearance of young leaves emerging from the whorl.

- Discolored, whitish patches on each side of the central vein. They become translucent and dry out. Vein and leaf edges remain green. Older leaves are not affected.

Diagnosis confirmation

Soil analysis is the most reliable. Zinc content is calculated according to soil pH. Foliar analysis, performed at flowering on the ear leaf, can confirm with a threshold content of 15 mg Zn/kg.

Risk Situations

- Zinc-poor soils

- High organic matter content

- High pH

- Phosphorus-rich soils

- Low temperatures

Impact on yield

In true deficiency, yield losses can reach up to about twenty quintals per hectare.

If the climate is cold and humid, deficiency can be induced by soil conditions unfavorable to zinc uptake. Symptoms are then transient and there will be no yield impact.

Iron

Symptoms

Iron deficiency, also called iron chlorosis, first appears on new leaves. These yellow between the veins, which remain green except in extreme cases. Often, symptoms are only visible on part of the plant.

Diagnosis confirmation

- Soil: Soil analysis is not very reliable. Indeed, the link between soil ferric concentration and iron uptake by plants is not well known.

- Plant: Plant tissue analysis is much more reliable to measure iron availability.

Risk Situations

- High lime concentrations (and consequently high pH)

- Extreme imbalances with other micronutrients such as molybdenum, copper or manganese

Boron

Symptoms

- Very upright posture from 6-7 leaves.

- Whitish interveinal discolorations from the 7-leaf stage. They progress to give a striped leaf appearance.

- Leaves are pressed against the stem.

- Sterility: absence of male or female reproductive organs.

Diagnosis confirmation

Foliar analyses do not allow diagnosis. Perform soil analysis. Boron extracted with boiling water (deficiency threshold: <0.2 mg boron metal/kg).

Risk Situations

- Soils containing very little boron.

- Originally acidic sandy soils whose pH has been excessively raised.

Impact on yield

Very serious impact if no intervention. There can be a total crop loss.

Molybdenum

Main symptoms are reduced growth and pale green foliage. Curved leaves are found on young shoots. However, molybdenum deficiency is very rare.

For more information on deficiency identification by crops, please consult the Arvalis accident sheets.

Tools to help identify deficiencies

DST (Decision Support Tools) exist to help identify deficiencies seen:

Correction and prevention

When deficiency symptoms are visible, the plant's undernutrition state is already advanced. In this case, apply an anti-deficiency treatment, foliar or soil-applied.

Once diagnosis is made, several correction strategies are often possible. In case of severe deficiency, foliar application is recommended for rapid correction. In some cases, multiple applications may be necessary. In contexts with recurrent deficiencies, soil applications can be considered. Recommended doses will cover needs for several years and will only be renewed after soil analysis control.

Do not invest blindly. Applying "cocktails" of elements is to be avoided, especially copper-zinc-manganese mixes[3]. It is better to target the deficient micronutrient.

In case of double deficiency, it is preferable to correct one by soil application and the other by foliar application.

Nitrogen

Preventive solutions against nitrogen deficiency

Split the input by applying a limited dose at sowing (20 to 40 kg N/ha) and the remainder between 6 and 8 leaves.

Curative solutions against nitrogen deficiency

Nitrogen fertilization, soil or foliar, is necessary to compensate deficiencies. If deficiency is confirmed, nitrates are preferable as they are directly assimilable by the plant.

For more on managing nitrogen deficiency on cereals and on maize.

Phosphorus

Preventive solutions

First, perform a soil analysis. If soil is poor, apply phosphorus close to sowing. Avoid applying after tillering begins as correction will be only partial. Plants are especially sensitive to deficiency during juvenile phase. If soil is adequately supplied but input is essential to compensate exports, timing is not critical.

Curative solutions

Apply phosphorus as soon as symptoms appear.

Minimum dose: 50 kg P/ha.

Correction is only partial if application occurs after tillering begins. In any case, complete correction of deficiency is not possible. Soil pH For more on managing phosphorus deficiency on cereals and on maize.

Potassium

Curative solutions

When symptoms are confirmed, it is essential to fertilize with a potassium sulfate solution. Generally, it is important to compensate exports to avoid curative treatments.

- Apply potash at sowing. For soils with very low K availability, localized potassium fertilizer at maize sowing is desirable.

- Minimum dose to apply is 60 units/ha of K2O.

For more on managing potassium deficiency on maize[4].

Sulfur

Preventive solutions

In risk situations, apply 30 to 50 kg/ha of SO3 from beginning of tillering to 1 cm ear stage, but avoid application before winter as sulfur may be leached.

Curative solutions

As soon as symptoms appear, apply 20 to 40 kg/ha of SO3, preferably by foliar spraying. Choose a 10% ammonium sulfate solution or micronized sulfur form.

For more on managing sulfur deficiency on cereals and on maize.

Calcium

Preventive solutions

- Choose varieties more efficient at calcium uptake.

- Reduce use of ammonium-based fertilizers.

- Inspect the field regularly and remove fruits with symptoms.

- Add organic matter (manure, organic mulches, compost) to the soil.

Curative solutions

Calcium fertilizers can be applied to seed or foliar. For foliar fertilization, pay attention to fruit development stage. If fruit is not fully covered, there is risk of degeneration.

Apply calcium-rich substances such as algal lime, basalt meal, burnt lime, dolomite, gypsum or lime slag.

Magnesium

Preventive solutions

Adjust soil inputs according to soil magnesium availability analysis and soil type.

- In acid soil: Magnesium lime amendment, 200 kg/ha for 3 years on sand and 5 years elsewhere.

- In neutral soil: All product forms usable, but sulfates act faster. Apply 30 to 50 kg/ha/year.

- In calcareous soil: Magnesium sulfate to spray on leaves. Apply 30 to 50 kg/ha/year.

Curative solutions

As soon as symptoms appear, spray a soluble magnesium fertilizer on the leaves, at a concentration of 5 to 10% in water and an application of 20 to 40 kg MgO/ha.

For more information on managing nitrogen deficiency in cereal grains and in maize.

For copper

Preventive solutions

This deficiency has become exceptional in France. Soils with a high organic matter content and rich in limestone pose the highest risks. Indeed, soil organic matter strongly complexes copper, and high pH (limestone soils, overliming) promotes the formation of insoluble cupric compounds.

In this case of deficiency, only a preventive action is possible, because once specific symptoms are visible, correction is no longer effective.

Only a preventive soil application is possible. Apply 5 kg/ha of metallic copper on the surface because copper is very immobile in the soil. This application corrects copper deficiency for 5 to 10 years.

For more information on managing nitrogen deficiency in cereal grains.

For manganese

This deficiency is observed on originally acidic, sandy or loamy soils, whose pH has been excessively raised. It is also found in loose soils rich in organic matter and/or rich in active limestone, with pH>8, with a crumbly structure of the worked layer.

Preventive solutions

Soil applications are not recommended as they are not very effective. In risk situations, avoid working the soil too finely and too deeply. Limit to the seedbed. Rolling the soil only reduces the deficiency; it does not eliminate it.

Curative solutions

As soon as symptoms appear, spray manganese sulfate, manganese oxide, or chelated manganese on the leaves.

Apply 500 g/ha at symptom onset. Repeat the application one month later. If the deficiency is severe, 3 applications may be necessary. The third will be done during stem elongation.

For more information on managing nitrogen deficiency in cereal grains and in maize.

For zinc

Preventive solutions

An application of 4 to 6 kg of zinc/ha, at the time of sowing (localized fertilizer), prevents zinc deficiency for 3 to 4 years. The form does not matter.

However, true deficiencies are rare. On the other hand, pseudo-deficiencies are frequent in sandy soils or in crusting loams, during years with cool and wet springs. To remedy this, a curative foliar zinc application is recommended.

Curative solutions

Foliar spraying: 500 to 600 g Zn/ha can correct a moderate zinc deficiency.

For more information on managing nitrogen deficiency in maize.

For iron

Preventive solutions

- Choose a soil adapted to the requirements of the cultivated plants: do not plant acidophilic crops in calcareous soils.

- Add manure or compost.

Curative solutions

If soil applications of iron are not necessarily effective, iron deficiency can be easily corrected by a foliar application of iron chelates (EDTA or EDDHA). It is also necessary to lower the pH to prevent this situation from recurring, for example by using manure or compost, ammonium sulfate as a nitrogen fertilizer which acidifies the soil, or elemental sulfur which oxidizes and thus lowers the soil pH.

For boron

Curative solutions

Spray a borate fertilizer with 300 g of metallic boron/ha.

For more information on boron deficiencies in maize

For more information on managing deficiencies by crop, we invite you to consult the Arvalis accident sheets.

Fertilization reasoning

Fertilization reasoning, which includes all organic and mineral inputs provided by the farmer to meet the nutritional needs of the cultivated plant, is important to allow a balance of the plant.

Excessive fertilizer inputs can result in favoring a number of bio-aggressors, notably due to temporary nitrogen excess:

- Development of a dense crop foliage creating a humid microclimate favorable to disease development and facilitating the spread of pathogens due to the proximity of plant organs.

- Nitrogen exploitation by weeds

- Attractiveness of the crop to pests (palatability, quantity of nutritional resource) and significant vegetative growth favoring movement from plant to plant.

Conversely, well-controlled inputs can make crops more competitive against

weeds (earlier and more vigorous development) and also more resistant to pest attacks (crop advanced to a less sensitive stage, better overall plant condition).

To reason fertilization, it is important to know the nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium contents in the soil before the crop, during it or in the plant. Fertilization reasoning methods are of several types:

- Dose adjustment during the campaign to avoid excesses and deficiencies depending on soil content (analysis), the climatic context of the year, and crop status (Decision Support Tools and harvest objectives).

- Splitting of inputs to avoid overdoses at certain periods.

- Localization of inputs favoring plant absorption zones (sowing rows, foliar applications).

Decision Support Tools (DSTs)

A wide range of DST (Decision Support Tools) exist and the services they offer around fertilization are varied:

- Nitrogen nutrition diagnosis.

- Fertilization management.

- Input reduction.

- Nitrogen balance calculation.

- Crop health monitoring at the plot level via satellite imagery.

- Dose modulation within the plot based on satellite data.

- Integration of sensor data sources for fertilization management.

- Return on investment calculator for amendment applications of certain elements.

- Portable soil measurement device usable in the field.

- ...

Find a directory of these DSTs here.

Further reading

Sources

- Recognizing deficiencies and intoxications in maize - Terre-net.

- Deficiency symptoms - Unifa.

- Trace element deficiencies: from diagnosis to correction strategy - Perspectives agricoles.

- Nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium: detect and correct these deficiencies - Yara.

- Calcium, magnesium, sulfur: detect and correct these deficiencies - Yara.

- Foliar fertilizer: cereal guide - Agriconomie.com.

- Properly diagnosing a deficiency - Arvalis-infos.

- Reason fertilization by practicing split or localized applications - EcophytoPIC.

- ↑ Recognizing deficiencies and intoxications in corn - Terre-net

- ↑ Loué 1993 and Comifer 2005

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Trace element deficiencies: from diagnosis to correction strategy - Agricultural Perspectives.

- ↑ Info sheet arvalis: http://www.fiches.arvalis-infos.fr/fiche_accident/fiches_accidents.php?mode=fa&type_cul=3&type_acc=1&id_acc=99