Water Pathway

In regenerative hydrology, it is important to understand the different water pathways at the plot and surrounding levels, to characterize volumes, and to know how to work with topographic tools in order to reclaim these flows for the benefit of agricultural production.

Natural Water Paths and Topography

Water naturally follows a number of paths, both on the surface and underground. Topography determines the paths water takes on the surface, and soil type (its composition) determines what happens below.

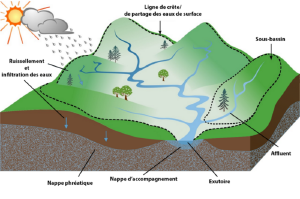

- Watershed: Defined as the basic unit of water management, it is a territory that drains all waters towards a common outlet. Watersheds exist at different scales, from small plots to large continental facades. They are delimited by ridge lines or watershed divides. The watershed (surface and groundwater) is distinguished from the drainage basin (only surface waters forming the hydrographic network). Each large watershed is composed of multiple sub-basins.

Drainage basin: surface water only.

Each plot of land, farm, or site belongs to a drainage basin and especially to a sub-basin delimited by the localized or very localized relief.

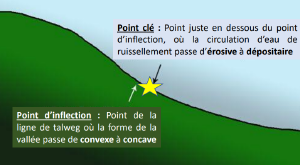

Key Landscape Lines: Landscape study highlights three important types of lines:

- Ridges: Water separation lines, distinguished into main ridges (separating large units) and secondary ridges (branching from the main).

- Valleys (or Talwegs): Valley paths, also distinguished into main talweg and branching secondary valleys.

- Contour lines: Lines connecting points of equal altitude, essential for water management in relief. They allow visualization of relief in 2D and indicate that water flow is always perpendicular to these lines in the direction of the slope. The shapes of contour lines help identify ridges and valleys.

Also identified are:

- Hydrographic network: Set of permanent watercourses (solid blue lines on maps) or intermittent (dotted lines) flowing over a given territory. Intermittent watercourses may be due to seasonal springs or runoff from precipitation in talwegs.

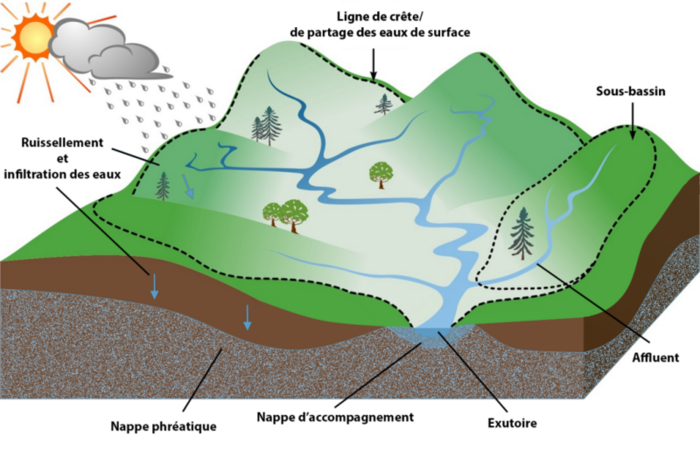

- Keypoint: On a slope, at the talweg level, it is the point just below the inflection point where the valley changes from convex to concave shape. It is a point where water flow changes from erosive to depositional. On a map, it is identifiable by the tightening of contour lines above and their spreading below. The keypoint is strategically located below the largest runoff drainage area while being above the largest gravity-irrigable zone, making it an ideal location for the creation of hillside reservoirs.

- Keyline (Keyline): Contour line passing through the keypoint. It separates a lower slope area downstream from a steeper slope area upstream. A succession of keypoints and keylines exists in a landscape, but they are not necessarily at the same height from one valley to another.

Artificial Water Paths

Human developments impact water movement even more:

- Plot drainage: Historically widespread and still practiced, it aims to artificially evacuate gravitational water from the soil to limit waterlogging. There are:

- Surface drainage: Often done by ditches at plot boundaries to capture surface and subsurface runoff.

- Subsurface drainage: Traditionally trenches filled with stones, today perforated plastic pipes installed at a certain depth to evacuate shallow water tables. Drainage networks, whether surface or subsurface, often end up discharging water into the natural hydrographic network.

- Roads and paths: These infrastructures, often accompanied by ditches, intercept and drain significant amounts of water which, instead of infiltrating, are quickly evacuated to the hydrographic network. Roads are often designed to facilitate this evacuation, sometimes contributing to downstream flooding problems. It is crucial to consider the existence of an artificial hydrographic network parallel to the natural one.

- Impermeable surfaces and roofs: Although sometimes representing small areas proportionally to the land, they generate significant runoff volumes that can be managed for beneficial or problematic purposes.

Roads in particular can intercept a large part of the water flowing between two plots they separate. Rather than infiltrating the downstream plot, the water follows the road and evacuates into the natural network.

Estimation of Water Volumes

Water volumes on a plot can be calculated by taking into account precipitation totals over a given period, the land surface, and its runoff coefficient (inverse of infiltration coefficient).

Runoff Coefficient

This is the percentage of precipitated water that runs off and is neither infiltrated nor evaporated. It is an estimate depending on several factors:

- Surface type: Impermeable surfaces (villages, roofs) have a high coefficient (around 0.9), while wooded areas have a very low coefficient (around 0.1). Roads have variable coefficients depending on their surface.

- Soil type: Sandy soils (draining) have a lower coefficient than clay soils (less permeable). The type of crop (cultivated field, pasture, forest) also influences this coefficient.

- Slope of the land: The steeper the slope, the greater the runoff and the higher the coefficient.

- Type of precipitation: Heavy rains quickly saturate the soil and increase the runoff coefficient.

Here are some approximate values of this coefficient:

| Land type | Runoff coefficient |

|---|---|

| Forest | 10% |

| Meadows, cultivated fields | 20% |

| Vineyards, bare soils | 50% |

| Artificial areas, roads | 90% |

Depending on soil texture, this coefficient can also vary[1]:

| Soil texture | Crops | Pastures | Forest |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sandy, gravelly soil | 20% | 15% | 10% |

| Loamy soil | 40% | 35% | 30% |

| Clay soil | 50% | 45% | 40% |

Estimation of captured water volumes

By knowing the precipitation height, catchment surface, and estimated runoff coefficient, the runoff water volume can be estimated using the formula:

Volume (m³) = (Catchment surface x Runoff coefficient x Rainfall total (mm)) / 1000

It is important to calculate at the level of different plots the amount of water that can runoff in this way. The primary goal is to minimize this runoff as much as possible, starting by implementing all agroecological principles (cover crops, organic matter addition, soil fracturing, grazing) – ideally water should infiltrate 100% into the soil. A penetration test can be done to compare soil infiltration capacity to maximum precipitation (see this page in particular).

If necessary, the overflow can be stored to infiltrate via buffer ditches (swales or baissières).

Topographic Data and Surveys

It is important to obtain an accurate graphical representation of the relief to study water management. This representation can be done with a professional (surveyor) or by oneself using the following tools:

- Macro scale (watershed): To study the area around one’s land, especially upstream, online tools like Géoportail are often sufficient. Géoportail offers aerial photographs, IGN topographic maps (with hydrographic network and contour lines generally every 5 meters), and cadastral plots. Google Earth is another option to visualize the land and create data.

- Micro scale (specific land): For higher precision at the plot level, several solutions exist:

- Photogrammetry by drone: Allows creation of precise 3D digital models of the terrain, useful for design, but remains an expensive professional solution. Amateur solutions exist with personal drones and open-source software.

- Géoportail: Although free and comprehensive in data, its altimetric precision (contour lines at minimum every 5 meters) may be insufficient for detailed local topography representation.

- Géoservice (IGN): Offers precise altimetric survey data (contour lines at one meter or less) free since March 2021. However, these raw data require processing with a Geographic Information System (GIS) software like QGIS to generate contour lines and overlay them on aerial images. A tutorial for using QGIS for this purpose is mentioned.

References

- ↑ Book: Hydrology 1 A Science of Nature. A societal management by André Musy, Christophe Higy, Emmanuel Reynard