Understanding the Protein Needs of Ruminants

Feeding ruminants is done using forages and concentrates. Within the framework of protein autonomy, it is essential to calculate rations for the herd in order to determine the area needed to produce the feed. We will focus on the protein part of the ration.

Estimating needs and supplies

Needs

In ruminants, most digestion takes place with the help of microorganisms in the rumen. The bacteria and protozoa of this rumen degrade feed into nutrients, and synthesize proteins (in the form of amino acids) which can then be assimilated by the animals via their intestine. Therefore, the protein needs of ruminants are expressed in PDI (Digestible Proteins in the Intestine). Below is a generic estimate of the average needs of some ruminants. However, the calculation of needs must be done case by case.

| Species | Characteristics | Average PDI needs (g/day) |

|---|---|---|

| Beef cattle | Charolais, BW = 650 kg, early lactation | 800 |

| Dairy cattle | Holstein, BW = 650 kg, CP = 32 g/L, MP = 30 kg/day | 1920 |

| Dairy sheep | Lacaune, BW = 70 kg, CP = 56 g/L, MP = 3 kg/day | 247 |

| Dairy goats | Saanen, BW = 60 kg, CP = 32 g/L, MP = 3 kg/day | 185 |

Supplies

Once needs are calculated, it is necessary to determine the characteristics of the feeds, in particular their protein content in order to provide a coherent ration for the animals. Although the commonly used unit to quantify this content is MAT (Total Nitrogen Matter), it is not entirely suitable for ruminant farming. Indeed, the microbial activity in the rumen that degrades these proteins requires energy and nitrogen to be sufficiently effective. For this reason, proteins in feeds consumed by ruminants are distinguished into two categories:

- PDIN or Digestible Proteins in the Intestine small intestine (PDI) allowed by the nitrogen (N) supplied by the feed.

- PDIE or Digestible Proteins in the Intestine small intestine (PDI) allowed by the energy (E) supplied by the feed[1].

A ration is largely composed of forages, inexpensive and fiber-rich feeds, and may be supplemented or not with concentrates. Their feed value is calculated using various characteristics summarized in the table below.

| Type | Characteristics influencing feed value |

|---|---|

| Forage green | Species or origin for permanent grasslands, cycle (number of cuttings+1), stage. |

| Conserved forage | Species or origin for permanent grasslands, cycle, stage.

Method of conservation, harvesting conditions, dry matter content. |

| Concentrate feed | Nature (protein concentration, crude fiber, etc.). |

The PDIN and PDIE values of these feeds can be found, as averages, in the feeding tables developed by INRA. Some examples are given in the table below:

| PDIE | Gross PDIN | |

|---|---|---|

| Hay | 82 | 69 |

| Soybean meal | 220 | 320 |

| Maize silage | 98 | 61 |

| Dehydrated Alfalfa | 100 | 119 |

Limiting amino acids in the dairy cow

In dairy cows, the two amino acids most frequently considered limiting protein synthesis are lysine and methionine. Regardless of lactation stage, needs are 2.5% of PDIE for methionine and 7.3% of PDIE for lysine.[2] The contents of feeds in methionine (MetDi) and lysine (LysDi) are available in the INRA tables. If needs are not met, a decrease in milk protein content will be observed. A decrease in milk production is also possible.[3]

Example: Barley has a content of 102 g PDIE/kg DM. Within this PDIE, there is a LysDi content of 6.83% and MetDi of 1.88%. We can therefore predict the quantities of these two amino acids supplied according to the amount of barley included in the ration. If needs are not met, the response of the milk protein content (Protein Rate) can also be predicted.

Formulating a ration

There are 4 types of rations:

- Complete ration: This technique offers the farmer a considerable time saving, as it consists of mixing forages and concentrates beforehand and then distributing this mixture to the animals. There is no individual concentrate supply. While it also allows good rumen function, it takes into account an average production goal. In the case of dairy cattle, for example, high-producing cows will be underfed and low-producing cows will be overfed.

- Semi-complete ration: To avoid this drawback of the complete ration, the farmer can choose to reduce the energy portion of the ration and provide high-producing cows with a concentrate supplement. Low-producing cows will thus not be overfed. However, this requires a significant time investment from the farmer.

- Individualized supplementation: This time, feeding is fully individualized. Concentrates are administered animal by animal. This allows precise adjustment to the needs of each individual. However, it requires considerable time.

- Group ration: This feeding method consists of separating the herd into groups and creating a ration for each group based on production and/or lactation stage in the case of dairy cows.

In all cases, a well-balanced ration will have a supply of PDIE equal to the ruminant's PDI needs, and a supply of PDIN equal to or possibly greater than the supply of PDIE. Indeed, if PDIN<PDIE, there will be a lack of degradable nitrogen for the rumen microbial flora. A slight deficit, defined using the Rmic (Microbial ratio), can however be accepted for each species and production.

This Rmic ratio allows checking the proper functioning of the rumen. It is defined by the formula (PDIN – PDIE)/UF*, and must be greater than a threshold value, the Rmin (Minimum microbial ratio), to ensure good rumen function.

*UF is the forage bulk, a value also available in the INRA tables.

| Species | Characteristics | Rmin |

|---|---|---|

| Beef cattle | In lactation | -17 |

| Dairy cattle | MP = 30 kg/day | -4 |

| Dairy sheep | MP = 2 kg/day | -6 |

| Dairy goats | MP = 3 kg/day | -7 |

A more detailed table is available in the INRA tables (2007).

- If the Rmic ratio is above the threshold value, the ration is acceptable. However, if it is much higher, there will be more nitrogen in the urine and thus excessive nitrogen emissions which can have economic and environmental consequences.

- If the Rmic ratio is below Rmin, the ration must be revised. Three possibilities are then envisaged:

- Add to the ration a feed rich in fermentable nitrogen (example: urea as a feed supplement)

- Change the concentrates for a feed with a higher PDIN value (example: replace rapeseed meal with sunflower meal).

- Introduce a forage rich in PDIN into the ration (example: grass silage as a supplement to Maize silage).

Other needs (energy, minerals, trace elements and vitamins) must also be checked to avoid deficiencies.

Feeding strategies: case of dairy cows

Feeding strategies for dairy cows are most often based on the forage available on the farm supplemented by concentrates produced or not on the farm, to cover the animals' needs. If the energy density needed increases with milk production, the PDIE/UFL (Milk Forage Units) ratio varies little and a ratio of 100 g PDIE/UFL is considered ideal for a balanced ration [2].

A compromise must then be found between very different individual needs within the herd and a simplification of feeding while optimizing the use of concentrate feeds. For this, different strategies exist. Here are some examples of ration strategies studied from the protein feeding perspective.

Ration strategy for a dairy cow in mid-lactation

For this example, we choose a multiparous dairy cow of 700 kg, in mid-lactation, with a maximum potential production of 41 L, producing 34 L per day in the 16th week at 40 g/kg fat (Fat Content) and 32 g/kg protein (Protein Content). Her nitrogen needs are 2146 g PDI.

Her ration is detailed in the following table:

| Feed | PDIN

(in ration) |

PDIE

(in ration) |

Quantity ingested | PDIN supply | PDIE supply | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forage | First-cut orchardgrass silage, 1 week before heading, short stems, with preservatives | 112g/kgDM | 75g/kgDM | 17kgDM | 1904 g | 1275 g |

| Concentrate | Triticale grain | 72g/kgDM | 96g/kgDM | 4.8kgDM | 345.6 g | 460.8 g |

| Total | 2250 g | 1735 g | ||||

A deficit of 410g PDIE is observed. In this ration, energy is the limiting factor for microbial synthesis. Therefore, part of the triticale must be replaced by a concentrate richer in nitrogen. Soybean meal is chosen:

| Feed | PDIN

(in ration) |

PDIE

(in ration) |

Quantity ingested | PDIN supply | PDIE supply | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forage | First-cut orchardgrass silage, 1 week before heading, short stems, with preservatives | 112g/kgDM | 75g/kgDM | 17kgDM | 1904 g | 1275 g |

| Concentrate | Triticale grain | 72g/kgDM | 96g/kgDM | 2.3kgDM | 165.6 g | 220.8 g |

| Concentrate | Soybean meal | 377g/kgDM | 261g/kgDM | 2.5kgDM | 942.5 g | 652 g |

| Total | 3012 g | 2147 g | ||||

PDIE supplies now match PDI needs and PDIN supplies are higher than PDIE. This ration is therefore balanced from a protein point of view.

To check proper rumen function, we calculate Rmic (in our example it is a cattle with milk production so we use UFL):

(PDIN-PDIE)/UFL = (3012-2147)/23.5 = 36.8 > 0. Rumen function is ensured.

Feeding strategy for a dairy cow at pasture

For this example, a multiparous dairy cow of 650 kg BW, with a potential milk production of 32 kg, and nitrogen needs of 2040 g PDI. The grazed grassland is a permanent lowland grassland, grass height at entry is 12 cm and 5 cm at exit. Maize silage is provided as a supplement as well as barley grain.

| Feed | PDIN | PDIE | Quantity ingested | PDIN supply | PDIE supply | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grazed pasture | Permanent lowland grassland | 114g/kgDM | 98g/kgDM | 13.1kgDM | 1493.4g | 1283.8g |

| Forage | Maize silage | 61g/kgDM | 98g/kgDM | 3kgDM | 183g | 294g |

| Concentrate | Barley grain | 79g/kgDM | 101g/kgDM | 4.6kgDM | 363.4g | 464.6g |

| Total | 2039.8g | 2042.4g | ||||

PDIE supplies cover nitrogen needs well. However, PDIN supplies are slightly lower than PDIE, but this difference is acceptable.

To check proper rumen function, we calculate Rmic:

(PDIN-PDIE)/UFL = (2039.8-2042.4)/21 = -0.1 > -4

Thus, Rmic is well above the Rmin for dairy cows (-4). Rumen function is therefore ensured.

Limitations to consider

Digestibility of protein crops

Some forages or protein crop seeds are known to be flatulent and rather poorly digestible by ruminants. This is a factor to consider when choosing species to include in the ration. However, technical solutions exist to address this problem, notably through thermal treatment technologies such as "toasting", or "extrusion", which aim to increase degradability in the rumen and digestibility in the intestines of these feeds [4][5]. However, it should be noted that, outside the theoretical framework, the technical benefits of these technologies are sometimes debated [6], especially due to variability of observed results and their Economic viability.

Protein efficiency

In recent years, the concept of "feed versus food" has become one of the main societal criticisms of livestock farming. This concept draws an unfavorable material balance between feed given to animals and those produced by them for human consumption.

From the protein point of view, it is important to consider this observation holistically, taking into account the share of proteins consumed by animals that are not valorized by humans: this is the case for example of grasslands, or processing by-products.

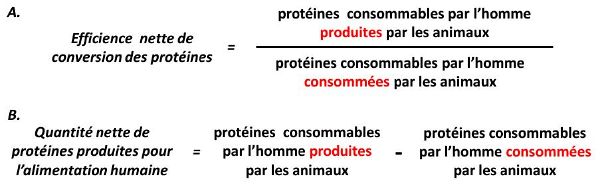

The net protein conversion efficiency is an indicator (developed by LAISSE et al. in 2018) that allows assessing this balance[7].

It is thus considered that, depending on ruminant farming systems, net protein efficiency is often close to or even less than 1. This means that about 1 kg of plant proteins consumable by humans is needed to produce 1 kg of animal proteins[8], and that under certain conditions animals are net producers of proteins consumable by humans.

Our series of guides on protein self-sufficiency

- Autonomie en protéines

- Appréhender les besoins protéiques des ruminants

- Valoriser les prairies pour accroitre l'autonomie protéique

- Produire des cultures fourragères riches en protéines

- Produire et consommer localement des concentrés protéiques

- Transformer et stocker les ressources alimentaires protéiques

References

- ↑ Techniques d'élevage, Expression des apports et des besoins en protéines des ruminants : PDI, PDIE, PDIN, 2011. https://www.techniquesdelevage.fr/article-expression-des-apports-et-des-besoins-en-proteines-des-ruminants-pdi-pdie-pdin-89694681.html

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 INRA, Practical guide: Feeding cattle, sheep and goats, Animal needs - Feed values. Éditions Quæ, 2010 ISBN: 978-2-7592-0874-6 (i.e. eISBN) ISSN: 1952-2770. http://www.civamad53.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Tables-INRA.pdf

- ↑ H. Rulquin, INRA, Interests and limits of methionine and lysine supplementation in dairy cow feeding: https://productions-animales.org/article/view/4219

- ↑ Chamber of Agriculture of Normandy, Technical note: toasting of protein crops, experience of a group of dairy farmers in Normandy, 2017. https://normandie.chambres-agriculture.fr/fileadmin/user_upload/National/FAL_commun/publications/Normandie/bl-toastage-Proteine-normandie.pdf

- ↑ P. Chapoutot et al., Rencontres Recherche Ruminants, Extrusion of protein crops modifies rumen degradation and intestinal digestibility of nitrogen, lysine and Maillard compounds, 2020. http://www.journees3r.fr/spip.php?article4775

- ↑ A. Peucelle, WEB Agri, Toasted or not, protein crops have similar growth performances, 2021. https://www.web-agri.fr/bovin-viande/article/180521/le-toastage-de-proteagineux-de-la-theorie-a-la-pratique

- ↑ G. Durand, Bordeaux Science Agro, Taking into account grasslands in the autonomy of protein in dairy cattle farms, 2020. https://www.inrae.fr/sites/default/files/pdf/3RDF2020-Actes_DEF.pdf

- ↑ S. Laisse et al., Feeding efficiency of farms: a new look at the competition between animal and human food, Gis Livestock Tomorrow, 2017. https://www.gis-elevages-demain.org/Actions-thematiques/Efficiency-protein-and-energy-of-animal-chains/Report-on-feeding-efficiency-of-farms