Prioritize the factors of production of a cultivated plant

In the quest to understand the reasons behind disappointing yields or sowing failures, it is imperative to establish a hierarchy of production factors. These production factors number 7: water, radiation, temperature, soil porosity, sowing conditions, variety choice, and fertilization. Therefore, a trial on micronutrient nutrition would rank 8th in this hierarchy. Although it can have an impact in case of pronounced deficiency, it is unlikely to allow surpassing yield ceilings, as the first 7 production factors are more important.

This article is largely inspired by research conducted by Lionel Mesnage (agronomy advisor), enriched by contributions from Martin Rollet (agronomist).

Production factors

Faced with the question "Why did my crop not yield?" or "Why did my sowing fail?", a thorough analysis of the factors at play is necessary. Placing each element in its order of priority allows establishing a more effective strategy for reflection and intervention. Factors such as soil, water, light, essential nutrients, sowing density, and plant health are parameters to consider before assessing the impact of micronutrient nutrition.

However, this does not minimize the importance of micronutrient nutrition. Indeed, in case of proven deficiency, its intervention can have a salvaging effect on the development of crops. Nevertheless, it is essential to recognize that to achieve optimal yield, a holistic approach is necessary, taking into account all production factors and their interrelations.

Water

The first production factor is water. As soon as a plant can no longer feed on water, its physiology stops. In this sense, it is crucial to understand that sowing density can play a significant role in managing this precious resource. Excessively dense sowing will exacerbate water demand, thus increasing pressure on available water resources. Therefore, it is advisable to recommend appropriate sowing densities, especially when the plant has a high compensation capacity.

The different stems compete not only for light but also for other nutrients such as water and nitrogen. Reducing this competition, through a lower sowing density, generally results in a notable improvement in ear fertility. This dynamic acts somewhat as a partial compensation at the potential expense of yield, induced by a reduced ear density.

Conversely, excess water causes anoxia by displacing oxygen from the soil. For example, one may observe a phenomenon of root rot of rapeseed.

Or poor degradation of organic matter in the soil with a bluish horizon, a sign of anoxia.

Radiation

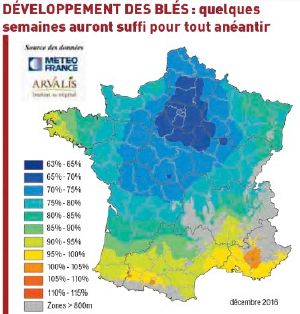

Plants, being photosynthetic, depend on light for their photon nutrition, which is essential for their growth and development. This need for light even outweighs the importance of traditional nutrients such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium (NPK). A lack of sunlight can thus cause significant yield drops, as observed in 2016, when promising harvests were ruined due to a light deficit during the flowering phase.

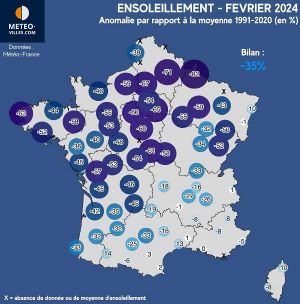

Similarly, at the beginning of 2024, crops struggled to green up early in the cycle after the first fertilizer applications due to a lack of brightness. Although this impact is relatively minor early in the cycle, it nevertheless highlights the crucial importance of light in the plant growth process.

Temperature

Annual plants need a minimum temperature to develop, called the vegetation zero. This temperature depends on the plant[3]:

- Wheat, barley: 0°C.

- Brussels sprouts: 3°C.

- Strawberry: 5°C.

- Corn, potato, rapeseed: 6°C.

- Sunflower: 7°C.

- Bell pepper: 7°C.

- Sorghum, vine: 10°C.

- Tomato, pear tree: 12°C.

- Citrus: 13°C.

- Cotton, banana: 14°C.

- Pumpkin: 16°C.

The concept of degree-days represents the heat accumulated by a plant. It is calculated as follows: (Daily maximum temperature – Daily minimum temperature)/2 – the vegetation zero of the species considered.

This correlates with a sum of degree-days, but also with the variety's sensitivity to vernalization (cold winter temperatures) and photoperiod. Temperature is therefore one of the elements allowing anticipation of crop phenological stages. However, from the beginning of stem elongation, the sum of temperatures remains fairly stable between two stages, regardless of the variety's earliness.

Porosity

The denser the soil, the harder it is for roots to penetrate. Here is a compacted horizon at 15 cm preventing flax from rooting:

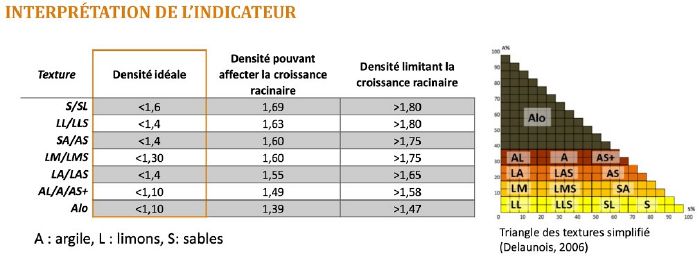

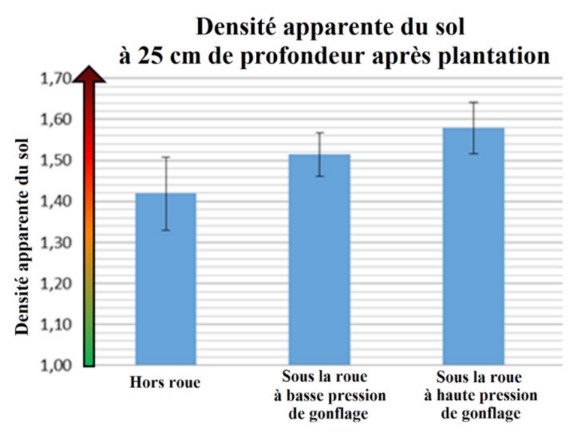

There are therefore densities not to be exceeded by soil type.

Annual plant roots are not equipped to drill like drills. Annual plants and cover crops do not have the capacity to penetrate excessively dense soils. Thus, low soil porosity affects plants' ability to explore the soil and therefore their ability to feed on nutrients. For example, a nitrogen residue present in the third soil horizon may be inaccessible to the plant if the soil density is high, making its use very complex.

A good indicator of soil compaction is root observation: if they circumvent obstacles or only penetrate along earthworm galleries, it indicates soil that is too hard. Conversely, the presence of Chinese radish in the mix can serve as a good indicator. This plant has no drilling capacity, so it will exit the soil as soon as it encounters resistance. If well-rooted radishes are observed at a depth of more than 35 cm, it indicates excellent physical soil fertility.

The thistle is a proven good marker of structural defects. Take a spade and look at where (at what depth) the suckers, i.e., the horizontal roots before any soil work, are positioned. It is from the dormant vegetative buds on these suckers that vegetative multiplication occurs if they are cut. An adaptation of the itinerary is therefore mandatory accordingly. (Anthony Frison)

Sowing conditions

As a general rule, sowing depth should be about 10 times the size of the seed. For example, a rapeseed seed has a diameter of 1.5 to 2 mm, so the optimal sowing depth is about 15 - 20 mm. Here is an example of too deep sowing linked to the wet conditions of autumn 2023. The seed is found at 6 cm depth whereas it should have been at 2-3 cm for good development conditions.

And here is another example of sowing in too wet conditions, with a poorly closed furrow in autumn 2023 and destroyed by autumn root weeding (position selectivity). Nothing was visible, which is normal, all the wheat died.

Variety choice

Variety choice is made according to production objectives (yield), but also the destination of the production (quality criteria). Of course, pedoclimatic factors and specificities of crop management in the local context must be taken into account.

Fertilization

Nitrogen and its fractionation are detailed on the page Nitrogen cycle in cropping. If a plant does not have the minerals it needs, its development will be compromised. As a reminder, regarding minerals, apart from nitrogen, cover crops do not fertilize but allow remobilization of minerals.

There are standards regarding micronutrient fertilization, and it is not necessary to go beyond them. For example, a wheat showing a deficiency in zinc will not show yield losses. Thus, based on current knowledge, it is not necessary to go beyond the table below, based on numerous trials from technical institutes.

- ↑ https://www.perspectives-agricoles.com/recherche-agronomie/physiologie-des-cereales-paille-comment-se-constitue-la-fertilite-des-epis Jean-Charles Deswarte, Physiology of cereal straw: how ear fertility is formed?

- ↑ Arvalis, Quality confronted with climate excesses, 2017.

- ↑ Valentin Kieny, Temperature & agriculture.