Nitrogen cycle in cropping

This article is based on a bibliographic research work. The objective was to provide a synthetic overview of the nitrogen cycle in agricultural soils. To best organize this work, questions were asked about the forms of nitrogen taken up by plants, the fate of consumed nitrogen, nitrogen deficiency situations, and also about the splitting of fertilization nitrogen applications. The answers are based on the latest results in the field.

What forms of nitrogen does a plant consume?

Our crops mainly consume nitrates (NO3-) and ammonium (NH4+) to a lesser extent. The absorbed ratios depend on the crop and its development stage. Recent research shows that cultivated plants are also capable of directly consuming part of the nitrogen in organic form, such as amino acids, even proteins. However, we currently do not know the potentials for direct absorption of organic forms by our crops.

What happens to nitrogen once applied to the soil?

It is often said that urea form would take several weeks to mineralize. This is actually false. Under cold conditions, a nitrogen dose supplied as urea or nitrogen solution is fully hydrolyzed into NO3- and NH4+ within a maximum of 3 to 8 days. Therefore, it is not necessary to adjust the timing of applications based on the type of nitrogen fertilizer used (except in the case of urea containing a urease inhibitor).

In this diagram, we can see that urea is fully mineralized in four days, even at very low temperatures.

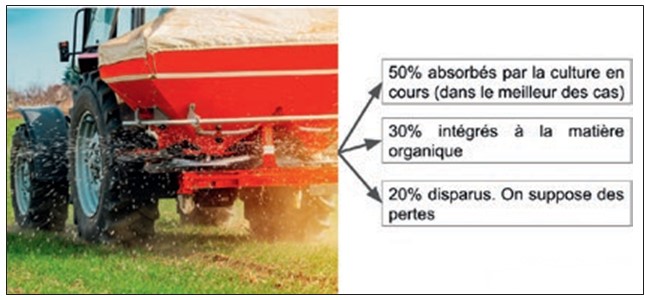

Once in the soil, the fertilizer is mineralized into NO3- and NH4+. This nitrogen will not be entirely available and taken up by plants; a significant portion will be immobilized by the biological activity and the organic matter in decomposition. This proportion is between 30 and 40 %.

This is the conventional view. In ACS, the equation is certainly somewhat modified with no mechanical tillage, cover crops and straw mulches on the surface that maintain a chronic nitrogen deficit. The portion absorbed by crops is logically lower with a larger part integrated into organic matter, while strongly reducing losses, especially by leaching. It is this reduction in availability that funds the growth of biological activity and overall the organic pool. Finally, this immobilization will gradually increase soil supplies to reduce, in the long term, fertilization levels thanks to progressive release.

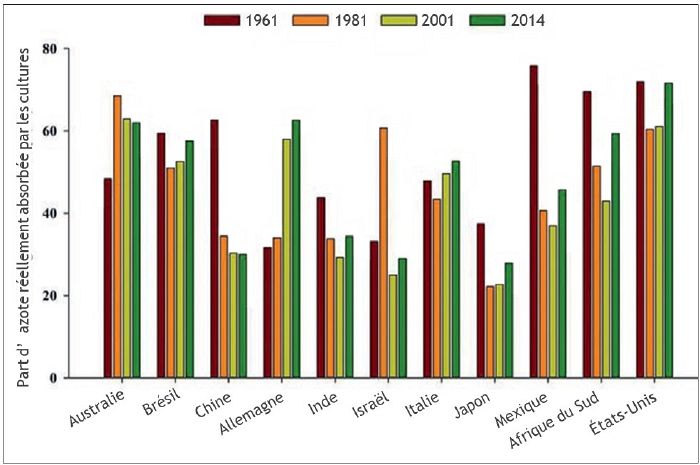

Next, what is the share of newly applied nitrogen that is actually absorbed by crops? This proportion is estimated around 50 to 60 % in France. In the diagram below, we see that this rate ranges from 30 to 70 % depending on crops, countries, and years. In short, there is no precision and soil conditions, climates, and also cropping practices are likely to greatly modify this ratio. From there, the main question is: how can I increase the share of nitrogen taken up by my crops from fertilizers?

The first thing to do is to seek to limit losses, which are around 20 % of applied nitrogen. These losses occur through volatilization and leaching. Volatilization can be greatly limited by incorporating nitrogen into the soil, choosing low-volatility forms and/or applying it just before a rainfall of 15 mm. Leaching can be greatly reduced by implementing cover crops systematically.

It is also necessary to be as close as possible to the physiological needs: for example, it is known that a cereal has very little need before the 1 cm ear stage. This is when supply must be maximal. After a pea or a faba bean (crops that can leave nitrogen residues exceeding 100 UN before winter), planting wheat can lead to very high losses during the autumn period. It is preferable to plant oilseed rape or, at least, establish a short intercrop cover between the legume and the autumn cereal.

And nitrogen deficiency?

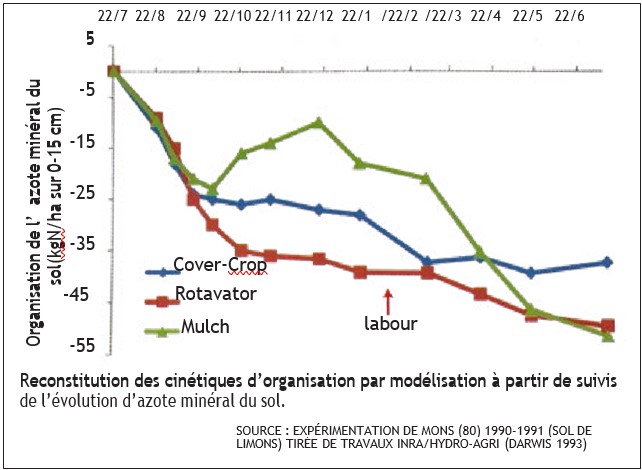

Incorporating carbon residues into the soil necessarily leads to nitrogen deficiency, as noted by Frédéric Thomas on the A2C website; it is accepted that one ton of straw incorporated into the soil will quickly immobilize between 10 and 15 kg of N/ha. Contrary to what one might think, a straw mulch on the surface also creates nitrogen deficiency. This nitrogen deficiency would be less severe than with incorporation due to the smaller contact surface of residues with the soil.

Compared to bare soil, nearly 15 UN are remobilized by October 10, versus 35 UN for straw incorporated with a rotavator. However, these types of experiments and measurements have a bias, as soil tillage to incorporate residues induces mineralization captured by the biological decomposition activity. Uptakes are certainly higher than those measured, which actually reflect a balance.

Finally, regarding ACS and the conservation of straw and residues on the surface, nitrogen mobilization is likely to be very strong in the top centimeters (3 to 5 cm) and prolonged, even if nitrogen is present at depth. This is one of the reasons why deep sowing of cover crops is successful.

And our friends the earthworms?

As shown by Marcel Bouché, in grassland ecosystems, earthworms play a predominant role in the nitrogen nutrition of plants[4]. For example, if we take wheat at 80 q/ha, looking at needs per quintal, about 3 UN, total needs are 240 UN. Uptakes will be 240 UN for 140-150 UN/ha depending on the protein content actually exported in the grains. This is a balance, but during its growth and development, the crop will actually consume nitrogen and continuously lose it through leaf and root loss or root exudates, thus consuming the same nitrogen multiple times. The level of exchanges is therefore different and certainly much higher than this balance.

In this way, annual flows of nearly 580 UN/ha have been measured on grasslands, passing through earthworms (1.3 t/ha). Again, there is not an input of 580 UN from nowhere, but a pool of nitrogen consumed and lost multiple times, circulating largely through earthworm digestive tracts and more broadly through biological activity. These earthworms are thus accelerators of mineralization, making available the self-fertility reservoir. This observation, beyond the quantities involved, also highlights the continuity of nitrogen supply, which is also a globalized element in the concept of self-fertility.

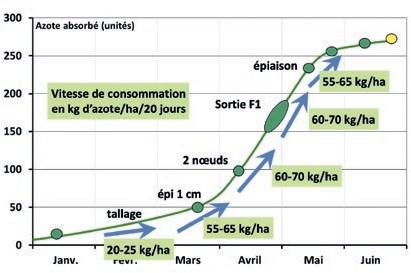

Nitrogen fertilization of wheat

Nitrogen needs are not the same at all wheat stages. From sowing to tillering stage, wheat consumes only about thirty units, then needs increase sharply once the 1 cm ear stage is reached. Thus, too early a large supply will not be fully utilized by the plant and will remain in the soil. One might think that given uncertain spring conditions, it is better to apply a large dose early to be safe, even if it remains in the soil, but although this strategy is possible, it has the disadvantage of atrophying the wheat root system, which can be problematic under dry conditions.

In this trial published in China, the more wheat develops under high nitrogen conditions, the smaller its root system, despite a very attractive aerial appearance. Conversely, wheat, like any crop, will prioritize its root system over shoot development if the soil lacks fertility. Therefore, under drying conditions, the attractive wheat is likely to perish faster due to its smaller root biomass. It is certainly a strategy between the two that must be developed and especially well adapted locally to soils, climates, and practices.

What about splitting fertilization on a cereal in ACS?

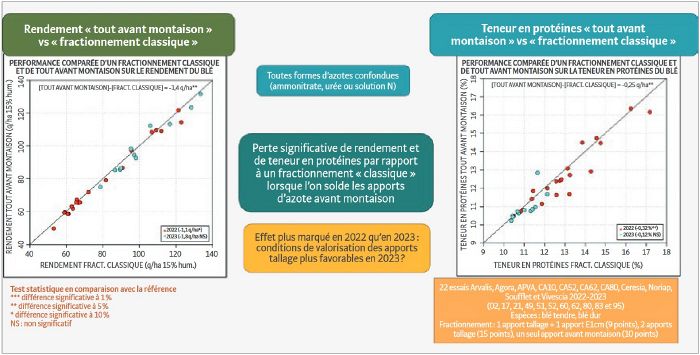

For two years, the first trial results have been coming in on nitrogen splitting on winter soft wheat in an ACS context. Notably, the Arvalis-Apad trials conducted in 2021-2023 on more than 20 platforms, those of the Chamber of Agriculture of Hauts-de-France and Thierry Tetu’s trials from 2019 to 2021. Examining the graph of the Arvalis-Apad trial results (figure 6), it is observed that splitting the nitrogen dose is beneficial to increase yield (1.4 q/ha) and protein content (+0.25 %), compared to a method where all is applied in one or two doses before stem elongation. It was also noted that the absence of nitrogen application during the tillering phase negatively impacts yield in ACS, due to delayed mineralization.

These findings corroborate the experiences of farmers practicing conservation agriculture, as they have observed that applying a substantial part of the nitrogen dose at the first application helps ensure good yield, while an additional application helps preserve crop quality.

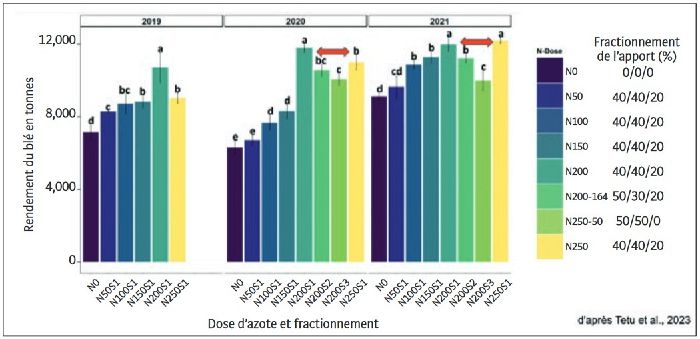

Kevin Allard and Thierry Tetu conducted a three-year field experiment to evaluate the impact of different nitrogen fertilization strategies on winter soft wheat in ACS and varietal mixtures. These wheats were planted after a legume. Nitrogen response curves were established, studying optimal splitting of nitrogen applications at three key stages: full tillering, first node, and last leaf visible. Splitting was applied as a percentage of the total nitrogen dose:

- S1 = 40 % / 40 % / 20 %.

- S2 = 50 % / 30 % / 20 %.

- S3 = 50 % / 50 % / 0 %.

In this ACS system and the particular context of productive soils in Hauts-de-France, the experiments showed that at the optimal fertilization level of 200 UN, a distribution of 40 % / 40 % / 20 % at full tillering, first node, and last leaf visible seemed the best option to achieve the highest plant productivity. These results show that optimal nitrogen splitting is actually more important than the total dose applied.

To summarize:

- Nitrogen needs are physiological and vary little between ACS and conventional.

- It is possible to apply in two doses, but this will impact protein and yield.

- The optimum remains to split.

See also Appi-N, mastering nitrogen fertilization

What if, in many sectors, nitrogen is not the limiting factor?

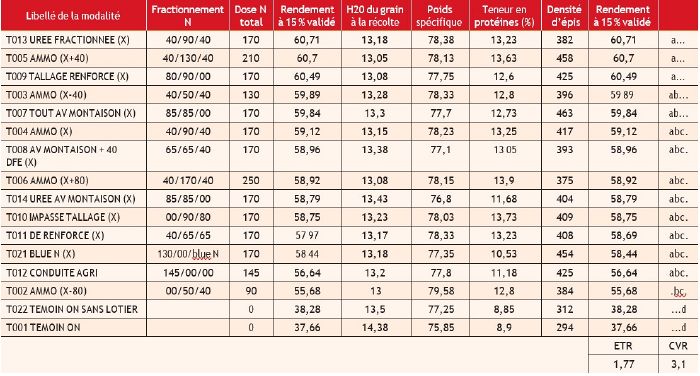

In this trial conducted on shallow soils under conservation agriculture, the 0 UN treatment yielded 37.7 q/ha of wheat, compared to only 57 q for 145 UN and 61 q for 210 UN. Thus, nitrogen efficiency appears quite low.

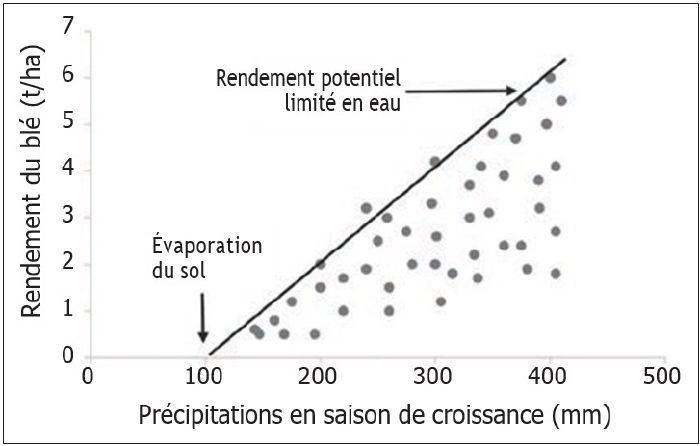

To understand this phenomenon, we must look at the work of the Grains Research and Development Corporation in Australia. These agronomists developed a concept of millimeters of water per quintal, which adds to the known kilogram of nitrogen per quintal. They show that nitrogen is a limiting factor only secondarily, and that if minimal water needs are not met, nitrogen efficiency collapses.

In a dry spring context often possible but very difficult to predict, would it not be essential to focus on water efficiency, by combining rainfall, useful reserve, and residual soil moisture measurements to optimize fertilization as best as possible? It is also necessary to consider that spring moisture also conditions mineralization and thus increases available nitrogen especially when self-fertility is high.

According to Frédéric Thomas, regarding nitrogen, it is probably best to forget precision at first given the number of random elements: uptake by biological activity and organic matter, climate impact on redistribution and mineralization, level of self-fertility being the main ones. Additionally, ACS, by greatly limiting leaching risks through biological soil organization and recycling by cover crops, provides more flexibility. However, since it is often necessary to overcome an organic barrier chronically nitrogen-deficient, it seems preferable to "load" and then choose the right application conditions rather than the ideal crop stage. Finally, measuring mineralization potential, more than residue levels, combined with zero-nitrogen controls seems the best way to assess the evolution of self-fertility to adjust overall doses according to yield goals.

Sources

Martin Rollet and TCS No. 126. January-February 2024.

- ↑ The true-false of wheat fertilization, Arvalis Editions, distributed by Négoce Agricole Centre-Atlantique https://negoce-centre-atlantique.com/sites/jenga/files/images/orki/2016_08_25_Guide_vrai-faux_fertilisation_azot%C3%A9e(1).pdf

- ↑ https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/plant-science/articles/10.3389/fpls.2023.1121073/full

- ↑ https://hal.inrae.fr/TEL-02843171/DOCUMENT

- ↑ M. Bouché, The role of earthworms in the decomposition and nitrogen nutrition in plants in a grassland

- ↑ Arvalis, 2020

- ↑ Yanhua Xu et al., 2019

- ↑ Gaëtan Bouchot, CA 52, ARVALIS