Enhancing Grasslands to Increase Protein Self-Sufficiency

In breeding of ruminants, grass, besides being a source of cheap feed, is often the main lever to increase the protein autonomy of the herd.

Grass is indeed the primary source of protein produced in France with 9 million out of 17 million tons of protein produced annually for human and animal feed [1]. Therefore, it must be considered among the resources available to define the ruminant feeding strategy.

Grass as a balanced feed source

Fresh grass is a feed resource to which most ruminants are naturally adapted. And despite a dry matter content (DM) quite lower than other feeds (12 to 18%), it offers good energy values (around 1 UFL/kg DM) and protein values (150g PDIN/kg DM, and 100g PDIE/kg DM) [2].

Moreover, it is one of the most digestible and palatable forages, with very good energy density depending on stages (UF/UE). Its intake does not imply digestible protein deficiency (PDIE/UF ratio > 95 g) nor degradable nitrogen ((PDIN-PDIE)/UF > 0 generally). Among other virtues of grazed grass, one can also cite its sufficient supply of Ca and P for grass-legume mixtures, as well as its buffering capacity favorable to the prevention of ruminal acidosis [3].

Nevertheless, the protein content of a pasture is not constant and varies according to different factors :

- its composition,

- the physiological stage of its species,

- the exploitation rhythm (e.g., number of cuts),

- the harvested plant mass,

- soil fertility,

- practices of fertilization,

- health status,

- ...

Cultural techniques and productivity

To fully valorize the quality forage resource that grass represents, a breeder can rely on various technical levers. Their objectives may be diverse (and combined) : maximize the productivity of pastures, increase their resilience, improve their nutritional value, spread out grass resources over time, etc. Here are examples of practices available to breeders to maximize pasture productivity and optimize their use.

At the production itinerary level

Composition

In the context of a temporary pasture, the composition is an important factor both for its productivity, its nutritional value and also its climate resilience. Indeed, multi-species pastures or pastures with varied flora offer various advantages thanks to their diverse composition :

- fertilization and good CP content with prairie legumes (e.g., clover, bird's-foot trefoil, minette, alfalfa...),

- resilience to weather hazards with species and varieties adapted to different climates and conditions,

- adaptation to a specific ration or harvesting itinerary.

Lifespan

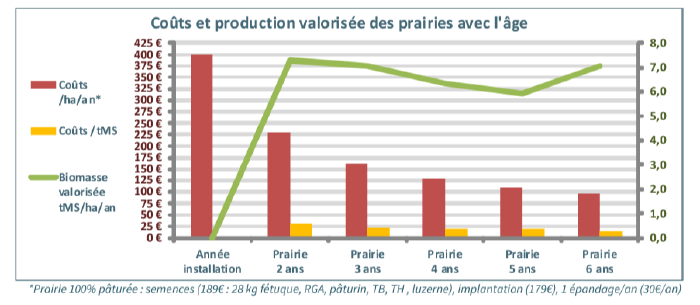

"Aging" temporary pastures is a practice to consider for maintaining high protein autonomy. Because when properly maintained, temporary pastures can maintain a high productivity level (7T DM/ha in the west of France for pastures over 6 years old), with a stable protein quantity and increased economic benefits (See graph below) [4].

Overseeding

In the same logic, overseeding or renovation consists of supplementing or reinforcing the flora of a pasture without destroying it. This practice should be adapted according to sanitary or climatic hazards (notably droughts) to revitalize affected areas or to increase species and varietal diversity. It is notably one of the levers to increase the nutritional value of a temporary pasture or permanent pasture, by renovating it with legumes. This practice generally takes place in summer, and is more effective after overgrazing or mowing as well as possible superficial work with a disc tool [5] [6].

Fertilization

It is established that fertilization of pastures directly influences the PDIN content of the plants composing it [7]. Therefore, nitrogen inputs must also be considered in relation to the protein autonomy strategy. For pastures containing legumes, needs are often low and the following restitutions are estimated :

| Amount of nitrogen supplied according to the weighted annual legume rate | |||

| Pasture production t DM/ha | Less than 10% | 10 to 30% | More than 30% |

| 5 | 0 | 40 - 30 | Total input limited to

a maximum of 50 kg N fertilizer equivalent at the beginning of the season |

| 6 | 0 | 50 - 40 | |

| 7 | 0 | 55 - 45 | |

| 8 | 0 | 65 - 50 | |

| 9 | 0 | 70 - 55 | |

| 10 | 0 | 80 - 60 | |

| 11 | 0 | 87 - 67 | |

| 12 | 0 | 95 - 75 | |

| Values in Bold correspond to the amount of nitrogen supplied by white clover.

Values in Italic correspond to the amount of nitrogen supplied by other legumes. | |||

However, it is sometimes considered that a mineral supplement to these restitutions is desirable. For example, the end of winter, or an input upon reaching 200°C days allows promoting earlier grass growth and thus guarantees a certain ratio with legumes; or after grazing or mowing to promote regrowth [9].

For high-yielding mowing pastures fertilized mainly with mineral nitrogen, special attention must be paid to sulfur deficiencies (since exports exceed atmospheric deposits and there is no restitution via grazing). In case of deficiency, sulfur fertilizer input can have a strongly positive impact on pasture productivity and protein content [10].

Defoliation and topping

Defoliation consists of grazing grasses before an early development stage (generally ear at 5 or 10 cm depending on ruminants), to slow the growth of their vegetative organs without cutting the ear. Besides providing an alternative feed source at the end of winter, this practice generally has no negative impact on pasture productivity : under certain conditions it can even densify them, or increase the nutritional value and digestibility of the cuts [11].

Conversely, topping corresponds to premature exploitation of the pasture, but once a certain ear emergence stage has passed : the ear is then cut off. The interest of this exploitation mode is limited to permanent pastures as well as certain species that have the capacity to re-erect ears the same year (such as Italian ryegrass, Bromes, etc). Topping then allows the breeder to keep their forage standing longer, or even harvest mainly leafy regrowth, more palatable and nutritious than ears, for less re-erecting species [12].

At the harvesting itinerary level

A protein autonomy strategy based on grass resources necessarily includes reflection on the mode of exploitation. Indeed, harvesting practices determine the amount of forage produced, its nutritional value, as well as the spreading of periods during which it can be valorized. Here is a list of solutions available :

Grazing

Rotational grazing

Rotational grazing refers to the subdivision of pasture plots, and the implementation of an intensive grazing rotation (animals stay only a few successive days on the same plot), to maximize the efficiency of grass consumption. It generally fits into low-input systems and allows good feed autonomy (and thus protein autonomy) at low cost.

Listen to the podcast from the Chambers of Agriculture of Normandy on the subject by clicking here.

Grazing duration [13]

Grazing being probably the least expensive "harvesting itinerary", some strategies seek to maximize it.

- For summer grazing, it is suggested for example to adapt the composition of temporary pastures, to include species with a capacity for late spring growth (Late English ryegrass, Timothy, ...) or regrowth in summer (alfalfa, orchardgrass, tall fescue, brome, chicory, plantain ...).

- For winter grazing, the main obstacle is soil bearing capacity so it is sometimes recommended to select the oldest pastures which are more resistant. Similarly, species with autumn growth can be included.

David Libot, a dairy farmer in Loire Atlantique, decided to focus on optimizing grazing which allowed him to reduce his inputs, gain feed autonomy and lower his costs. When asked what he would do if he had to do it again, he replies : "Maybe I would start earlier! I am happy to say that the milk I produce is healthier and of better quality than 10 years ago."

Wet method

Green feeding

Green feeding is an alternative to 100% grazing, it consists of bringing freshly cut grass to the trough the same day. It notably avoids trampling problems in wet conditions, valorizes too distant plots, or limits the "refusal" effect. It offers advantages comparable to grazing : dynamic mowing strategies, good control of the ration's nutritional value (notably protein for early cuts, characterized by higher CP content).

Wet storage: Silage and wrapping

The objective is to preserve forage with a low DM content.

The principle of wet storage is to rapidly lower the pH and maintain strict anaerobic conditions to stop all enzymatic activities of the plant and limit the development of harmful bacteria.

Silage

It is the storage method that allows to better preserve the energy value of grass, provided also of a early mowing, a good wilting (up to 35% DM), a good packing and a hermetic silo closure[14]. Once the forage condition is stable, and there is no more microbiological or enzymatic activity, silage, as long as it has not been opened and the plastic is intact, can be stored for very long periods.

Wrapping

By its DM content, wrapping is between silage and hay (45-75% DM). If baling and sealing are faster, and anaerobiosis is more effective, the forage is not chopped and sugars are less available for acidification. Thus, acidification is slower. Moreover, there is a higher risk of contamination than for silage, and quality variability is observed because each bale is a silo and can evolve differently.

Dry storage

Hay

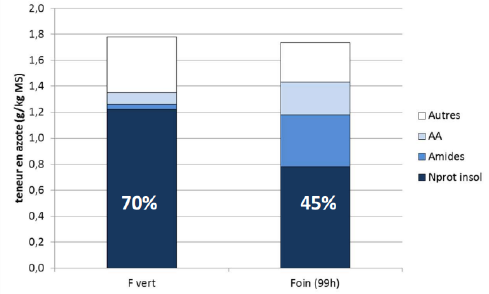

This time, forage is preserved with a high DM content, above 85%. The objective is to rapidly reduce the water content of the forage to stop all enzymatic activities of the plant. As long as DM content is below 85%, the plant continues to respire and enzymatic processes continue. There is then degradation of insoluble proteins into soluble nitrogen (AA, amides), more important the slower the drying. Hay thus allows better quality of nitrogenous matter supplied, as shown in the graph below. However, slow drying causes undesirable energy losses of the forage. Moreover, respiration causes heating of the forage and thus fermentations. This forms non-degradable nitrogenous matter, decreases digestibility and intake. It is therefore essential that wilting is done as quickly as possible. Losses are also possible due to rain, which lowers energy and protein content and facilitates development of certain bacteria and molds.[15]

Our series of guides on protein autonomy

- Autonomie en protéines

- Appréhender les besoins protéiques des ruminants

- Valoriser les prairies pour accroitre l'autonomie protéique

- Produire des cultures fourragères riches en protéines

- Produire et consommer localement des concentrés protéiques

- Transformer et stocker les ressources alimentaires protéiques

References

- ↑ France-Prairie, Les mélanges pour prairie au service de l'autonomy protein, accessed in March 2022. https://franceprairie.fr/les-melanges-pour-prairie-au-service-de-l-autonomie-proteique

- ↑ P. Roger, Chamber of Agriculture of Brittany, Nutritional value of grass : convincing results in Morbihan, Cap breeding No. 32 - February / March 2009 pages 21 to 23. http://www.synagri.com/ca1/PJ.nsf/TECHPJPARCLEF/10039/$File/Valeur%20alimentaire%20de%20l'herbe%20-%20des%20r%C3%A9sultats%20convaincants%20dans%20le%20Morbihan.pdf

- ↑ R. Delagarde (INRA), Value of grazed grass, Grazing Guide : 100 sheets to answer your questions - Reference : 0018303007– ISBN : 978-2-36343-938-3 March 2018. https://www.encyclopediapratensis.eu/product/guide-paturage/valeur-de-lherbe-paturee/

- ↑ O. Tremblay, R. Dieulot, CIVAM Network, Why / how to properly age grass-legume association sown pastures?, PERPet Project, 4AGEPROD, 2020. https://www.civam.org/ressources/reseau-civam

- ↑ D. Hardy, IDELE, Overseeding of permanent pastures, CAP-Proteins, 2022. https://www.cap-proteines-elevage.fr/le-sursemis-des-prairies-permanentes

- ↑ B. Osson, R. Depoix, SEMAE, Successful overseeding of legumes in pasture, seed and plant interprofessional 2021. https://www.semae.fr/communique/reussir-le-sursemis-de-legumineuses-en-prairie/

- ↑ J.-L. Peyraud, INRAE Mixed Research Unit on Milk Production, Nitrogen fertilization of pastures and dairy cow nutrition. Consequences on nitrogen emissions, 2000. https://productions-animales.org/article/view/3769/11753

- ↑ GREN Brittany, accessed March 2022 on the "Herb'actif" platform, magazine of pastures and prairie forages for all livestock professionals, SEMAE, A mixed pasture can require nitrogen fertilization.https://herbe-actifs.org/agronomie/fertilisation-azotee-pour-prairie-de-melange

- ↑ Arvalis Plant Institute, Nitrogen Fertilization : the engine of the pasture, 2009. https://www.arvalis-infos.fr/fertilisation-azotee-le-moteur-de-la-prairie-@/view-4086-arvarticle.html

- ↑ M. Mathot, L. Thélier-Huché, R. Lambert, Sulphur and nitrogen content as sulphur deficiency indicator for grasses, European Journal of Agronomy, Volume 30, Issue 3, Pages 172-176, 2009. ISSN 1161-0301, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eja.2008.09.004. http://www.fourragesmieux.be/Documents_telechargeables/MATHOT2009.pdf

- ↑ A. Brachet, RMT Prairies Tomorrow, Defoliation : early grazing and quality forages, Grazing Guide : 100 sheets to answer your questions - Reference : 0018303007– ISBN : 978-2-36343-938-3, 2018. https://www.encyclopediapratensis.eu/product/guide-paturage/le-deprimage-paturer-tot-et-avoir-des-fourrages-de-qualite/

- ↑ M. Gillet, INRA, Grass physiology and grazing, AFPF, 1981. https://afpf-asso.fr/index.php?secured_download=878&token=c16b0ba6e27c1efb0d74a94026afe433

- ↑ J-C. Emile, RMT Prairies Tomorrow, Grazing longer!, Grazing Guide : 100 sheets to answer your questions - Reference : 0018303007– ISBN : 978-2-36343-938-3, 2018. https://www.encyclopediapratensis.eu/product/guide-paturage/paturer-plus-longtemps/

- ↑ F. Guillois et al., 4AGEPROD project notebooks, Harvested grass : how to better grow, store and valorize it in Pays de la Loire and Brittany farms?, ISBN : 978-2-7148-0099-2, 2020. https://opera-connaissances.chambres-agriculture.fr/doc_num.php?explnum_id=158071

- ↑ Forage conservation and valorization of crop by-products, Philippe HASSOUN INRAE, 2021.