Zaï technique

The "Zaï" or "Tassa" technique is a traditional method used in certain regions of Africa to improve water retention and soil fertility in arid or semi-arid areas. This technique is particularly common in countries like Burkina Faso and Niger. Here's how to implement the Zaï technique in agriculture.

Description

Since the 1980s, Sahelian farmers have experimented with various soil and water conservation techniques to rebuild, maintain, or enhance the fertility of poor and crusted lands in certain areas known as "Zippéllé". One of the most appreciated techniques by farmers in northern Burkina Faso has been the system of planting pits (half-moons) or "Zaï" in the local language. This technique was imported from Mali and was adopted and improved by farmers in northern Burkina Faso after the droughts of the 1980s.

Principle

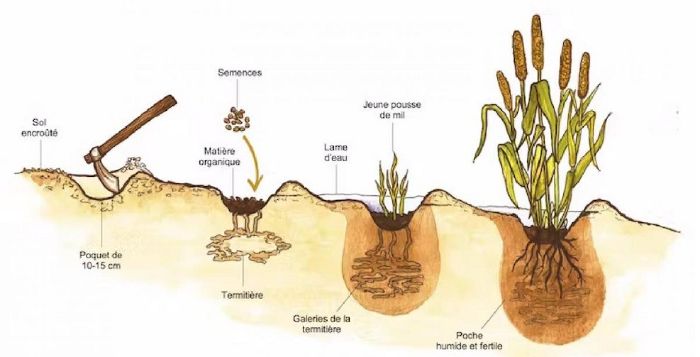

Zaï involves digging pits to concentrate runoff water and organic materials. The land must be prepared very early in the dry season by digging these basins and piling the soil into crescent-shaped ridges downstream. These micro-basins trap sands, silts, and organic matter carried by the winds. The entire field is surrounded by a stone bund or, alternatively, by anti-erosion dikes to control the very intense runoff on these crusted lands.

Organic matter is deposited inside these pits and covered with a thin layer of soil. Termites, attracted by the organic material, dig tunnels at the bottom of the pits, transforming them into funnels. After the first rains, approximately two weeks after the organic material is added, seeds can be sown.

Runoff water flows into these pits, creating pockets of moisture deep underground shielded from rapid evaporation. The Zaï technique therefore concentrates water locally, enriched by runoff and nutrients transformed by termites.

Objectives

The agricultural Zaï technique aims to :

- Promote infiltration on impermeable soils.

- Achieve normal to higher yields on crusted lands in arid areas.

- Collect water and make it available to crops.

- Increase soil water reserves.

- Recover crusted lands and enhance their value.

- Enhance soil utilization and aeration.

- Improve soil fertility by trapping fine particles brought by runoff water and wind.

Implementation steps

Agricultural Zaï pits are applicable in the Sudanian and Sahelian regions where the soils have been degraded by water erosion and have become uncultivated. These soils are usually bare, crusted, and hardened, generating a lot of runoff. They are typically installed on gently sloping land (less than or equal to 3%) with soils that are neither very sandy nor very clayey. Agricultural Zaï pits are practiced on rainfed crops.

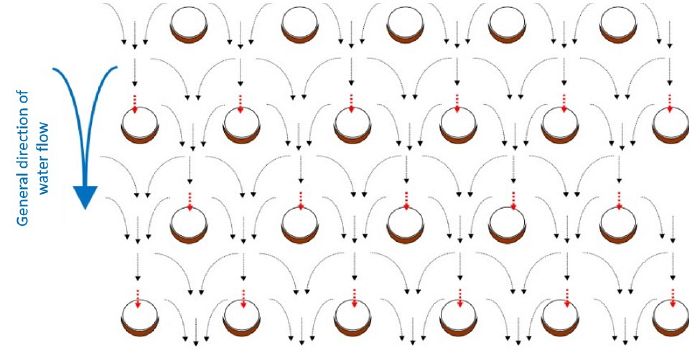

- Identify the general flow direction of rainwater and build a first contour line.

- Soil Preparation : Start early in the dry season (from November to June). On this first contour line, dig circular (or rectangular) holes in the ground, 20 to 40 cm in diameter and 10 to 20 cm deep, rejecting the soil in a crescent shape downstream, that is, in the direction of flow. The holes are spaced about 70 to 100 centimeters apart. Then move to the next line downstream from the first, ensuring a staggered arrangement, and so on down the slope. The pits can be dug manually using a daba (short-handled hoe) or mechanically (animal or motorized traction). The average density is 10,000 Zaï pits/ha[1].

- Fertilization :

- Organic Matter Input : With the first rains, add compost, manure, or other organic materials into each pit :(300 to 600g/pit = 1 to 2 handfuls of manure/compost = on average 3 t/ha). This helps enrich the soil with nutrients.

- Ashes and Other Amendments : Some farmers add ashes or other amendments to improve soil quality.

Cover this input with a thin layer of soil (5cm).

- Planting : Sow seeds after the first rains (at least 20 mm) inside each pit. These can be cereal crops or vegetables adapted to the region. Provide initial watering to help seeds establish in the pit.

- Maintenance and Monitoring : Monitor plant growth and provide additional water as needed, especially during dry periods. Protect young plants from animals and pests. Weed the pits at least twice per cropping cycle to prevent weed expansion. Sow in the same pits in the second year.

Mechanical Zaï technique

The adoption of the manual Zaï technique is limited by various constraints, one of the main ones being the high demand for labor. The operation, which takes place in the dry and hot season, is therefore arduous for farmers.

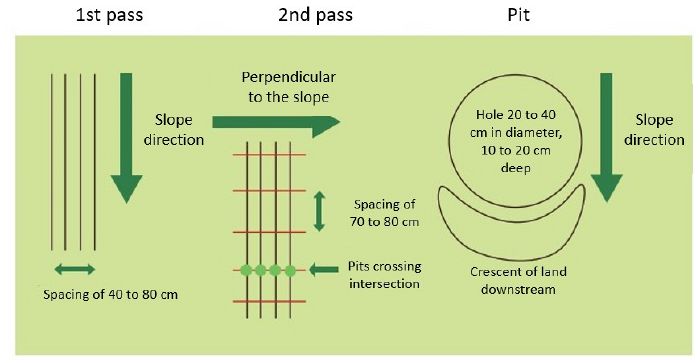

Mechanizing the operation is possible. It involves making cross passes with the soil-working tool in dry conditions using animal or mechanical traction. The first pass is made downhill : the spacing between passes corresponds to the spacing between pits. The second pass is perpendicular to the slope and crosses the first one. The spacing between passes corresponds to the spacing between planting rows.

The spacing between holes varies depending on the intended crop. For millet, which grows tall, it can be 80 cm x 80 cm. For sorghum, which is shorter than millet, it can be 70 cm x 70 cm. At the intersection of the 2 passes is the Zaï pit : the soil is excavated from the intersection points and deposited downstream of each pit.

Advantages

- Erosion protection : The pits help reduce soil erosion by slowing down water runoff.

- Water retention : They act as water reservoirs, allowing plants to access water for a longer period, even during dry seasons, as deep water storage reduces losses through evaporation and promotes groundwater recharge.

- Soil fertility : Adding organic matter enriches the soil, enhancing its fertility and ability to support plant growth. Trapping organic materials displaced by the wind in the pits also improves soil fertility.

- Soil regeneration : Efficient recovery of degraded and crusted lands in a short period.

- Improved crop yield : Early germination and deep rooting enhance cereal yields.

- Time saving : Weeding is limited to the pits, reducing labor for crop maintenance.

- Optimal manure utilization through localized application.

- Carbon sequestration.

- Ease of adoption by the population.

Limitations

- Intensive labor : Manual digging of numerous Zaï pits can be labor-intensive, requiring substantial manpower, which can be challenging in communities with limited labor. Estimated working time : 100 to 120 Zaï/man/day.

- Requirement for significant quantities of high-quality organic material.

- Risk of asphyxiation for young plants in case of heavy precipitation.

- Risk of plant attacks by termites attracted to manure when applied late.

- Dependency on climatic conditions : The effectiveness of the Zaï technique relies on precipitation to fill the pits with water. During prolonged drought years, the technique's efficiency may be reduced.

- Limited space : This method requires ample space between pits for optimal effect. In areas with limited space, implementing it on a large scale can be challenging.

- Adaptability : The Zaï technique may not be suitable in all contexts. Its success depends on specific soil, climate, and available resource characteristics.

- Limited lifespan : The lifespan of an agricultural Zaï is 1 to 2 years. After this period, pits need to be redug in the same location to allow the catchments to continue their roles and renew the organic matter.

To go further

- Zai pits - Greener Land.

- Zaï & Sahelian bocage in Burkina Faso, with Henri Girard:

- How the UN is holding back the Sahara desert:

This page was written in partnership with the Urbane project and with the financial support of the European Union.

Sources

- https://www.greener.land/index.php/product/zai-pits/

- Zaï agricole - Niger GDTE.

- La technique du Zaï - SECAAR.

- Les techniques d'agriculture de conservation peuvent-elles faire mieux que le Zaï manuel ou mécanisé dans le Sahel ? CIRAD-INERA.

- Cultiver sans eau ou presque : la technique du zaï au Sahel - CIRAD.