Understanding and Enhancing Fiber Digestion in Grazing

Knowing and strengthening fiber digestion in pasture allows to:

- Reduce refusals, promote the desired ruminal flora, secure the system by finding a balance between stock and pasture

- Avoid performance drops during dietary transitions, succeed in grassing and increase the share of grass in the diet

- Save working time, reduce fossil energy consumption, reduce costly purchases

- Achieve production goals with the feed resources available on the farm throughout the seasons

- Reduce pathologies related to dietary imbalances (acidosis, lameness, excess urea, grassing diarrhea, etc.).

From an economic, environmental and climate change perspective, it is important to recognize that forages (whether harvested or grazed) are less risky and less costly to obtain than concentrates and cereals.

Fiber is often mistakenly considered as a simple element to promote the mechanical functioning of the rumen. However, in ruminants, fiber (a constituent of plant cell walls) is a feed that can provide the majority of the nutrients necessary for production in farming.

Understanding digestion mechanisms

Fiber and starch: two distinct energy sources

The ruminant is a pre-gastric fermenter capable of valorizing lower nutritional quality feeds such as fiber or non-protein nitrogen. This also gives it the advantage of eliminating certain toxins (alkaloids, cyanides…) very early in the digestive tract.

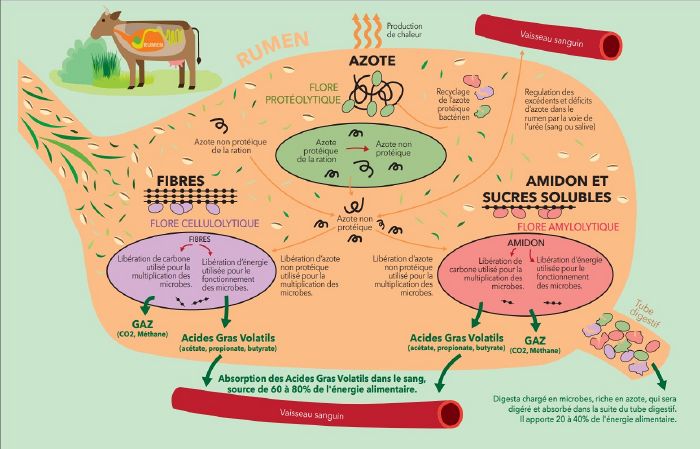

Starch and soluble sugars are carbohydrates, i.e. carbon chains of varying lengths that are easily utilized by ruminants. Present in ingested feeds, these carbohydrates undergo degradation in the rumen by microbes present in large quantities.

Thus fiber (cellulose, hemicellulose) constitutes, just like starch or soluble sugars, a feed for the ruminant. It usually represents the main fuel for ruminants to meet energy needs and enable milk or meat production.

For all carbohydrates degraded in the rumen, the products released into the ruminal fluid are quite similar: Volatile Fatty Acids (VFAs), gases (CO2 and methane), and water. But the digestion of each carbohydrate is carried out by a specific microbial population.

Gases are expelled by eructation of the animal and VFAs cross the rumen wall to enter the blood and become energy sources for the ruminant itself. The energy provided by these VFAs represents 60 to 80% of the energy supplied by the ruminant's diet. The fermentation phase in the rumen is therefore the key phase of ruminant digestion!

Conditions for proper rumen function

Nitrogen is an essential component for the proper digestion of fiber, starch, and soluble sugars by the ruminal flora.

Nitrogen is essential for the multiplication of rumen microbes, and thus for the digestion of fibers or rapidly fermentable carbohydrates. These microbes, which are then rich in proteins, are subsequently digested along the digestive tract and provide the majority of amino acids to the ruminant.

The ruminant manages to regulate excess or deficiency of nitrogen:

- Excess nitrogen is evacuated into the blood by absorption through the rumen wall, then converted into urea by the liver to be excreted in urine.

- Conversely, when the animal's diet is not sufficiently nitrogenous, microbes can also benefit from nitrogen recycling, made available by the liver for the rumen. Also, within the ruminal fluid itself, some microbial proteins (nitrogen-rich molecules) can be converted back into urea to serve again for the multiplication of new microbes.

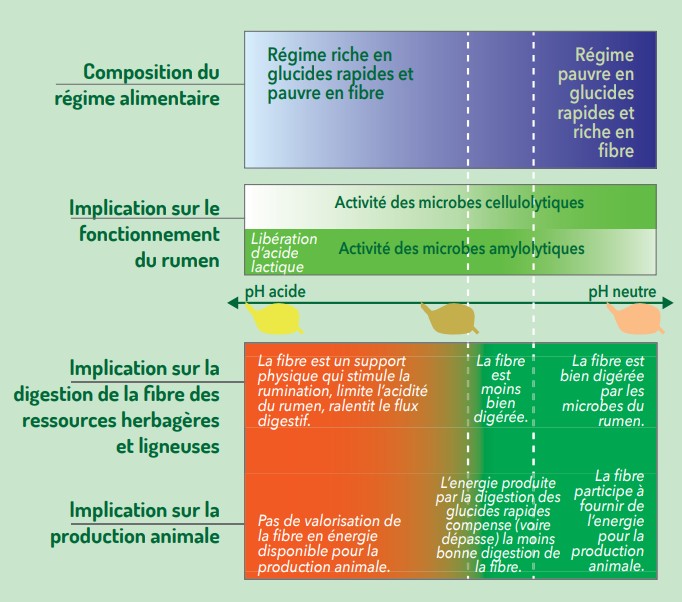

Microbial populations coexist or dominate depending on the ration composition.

The different microbial species in the rumen are adapted to co-exist by developing multiple and complex interactions, which confer remarkable stability. However, each microbial population tends to preferentially feed on one type of carbohydrate and secondarily on others. Several characteristics of the ruminal environment modify the proportion of different microbial populations:

- Starch and soluble sugars rapidly favor the growth of populations capable of fermenting them (amylolytic microbes), populations that then dominate the environment and leave little room for populations capable of fermenting fibers (cellulolytic microbes)

- Rumen acidification (induced by diets rich in starch or soluble sugars and by silage) significantly penalizes the multiplication of cellulolytic microbes, thus reducing the rumen's capacity to digest fiber.

Shifts from one microbial population to another occur at variable speeds. For example, the transition to restore a cellulolytic flora is longer than to restore an amylolytic flora.

Rumen function feedback controls feeding motivation.

As in all animals, feed intake is regulated by feedback mechanisms to allow the animal to adjust its ingestion to its nutritional needs. In ruminants, three main mechanisms are at work:

- Accumulation of material in the rumen stretches the walls and activates physical sensors. When the rumen is full, the animal feels a "physical satiety" that suppresses appetite.

- When nutrients accumulate in the ruminal fluid, osmotic pressure increases and the animal feels a "metabolic satiety" that suppresses appetite.

- When volatile fatty acids increase in the blood, glycemia triggers a "metabolic satiety" that suppresses appetite.

Assessing forage quality and complementarity

| Evolution of plant characteristics | Implications for assessing forage quality |

|---|---|

| At young stages (light green, tender), plants are low in fiber, rich in nitrogen and rapidly fermentable soluble sugars. | Forages provide useful materials (especially nitrogen) to digest other more fibrous feeds. |

| As they mature (taller, more rigid, but still green), plants gain fiber but retain good nitrogen content. | Forages are digestible and balanced. |

| At senescence (yellow or brown color), nitrogen decreases sharply, fibers remain present. | Fibers remain digestible, but energy production is proportional to nitrogen present in the ration. Forages can cover low to moderate nutritional needs; nitrogen supplementation from other ration components may be necessary to cover higher needs. |

| At degradation (gray or brown color), nitrogen is absent and fibers have already been partially digested. | Forages have very little nutritional value for the ruminant. |

Lignin is a molecule that binds to fibers to stiffen supporting tissues (stems, branches, trunk). It is not digested by the ruminant. It makes access to fibers more difficult for rumen microbes, which slows the release of volatile fatty acids from these fibers. This is why ruminants often preferentially consume plant parts with low lignified fibers: herbaceous plants, foliage and young shoots of "woody" plants, grass ears, straw…

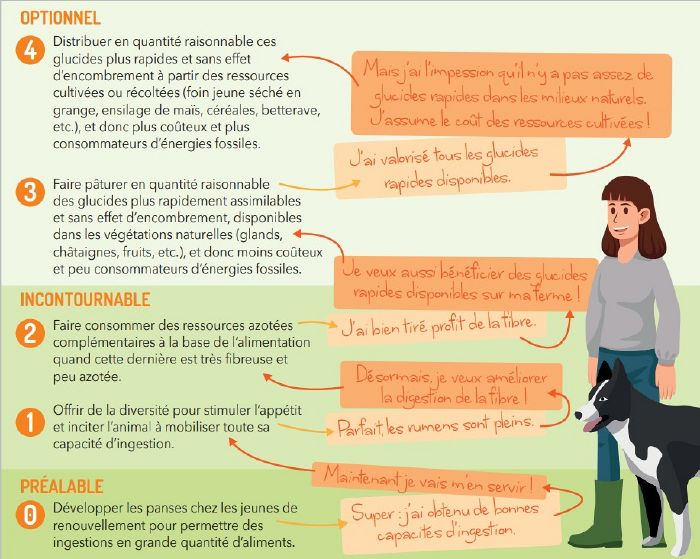

Seeing fiber as a feed and not as physical "bulk"

Because of its bulk effect, fiber has gradually been seen as a handicap, to the point of no longer being considered a feed. Fiber digestion indeed takes time (it requires rumination; it slows the flow of material in the digestive tract). But this is not time lost as long as the fiber is digested.

Once considered a feed, it becomes wise to improve learning through the education of replacement young stock, to promote rumen development (ingestion capacity).

Taking into account forage nitrogen for rumen microbes' needs

Nitrogen is an essential element for rumen microbes, thus essential for the digestion of forages and concentrates. When nitrogen is limiting for the rumen ecosystem, increasing ingested nitrogen can lead to increased microbial activity, thus increased production. But when nitrogen is excessive, the rumen and ruminant metabolism are inefficient at converting it into energy. This excess nitrogen is released into the environment as urea and causes long-term pathological problems in the ruminant, as well as environmental imbalances (water pollution).

Using rapidly fermentable carbohydrates without harming fiber digestion

Rapidly fermentable carbohydrates (soluble sugars, starches, pectins) allow to release nutrients more quickly and with less bulk effect than forages. They are therefore often used to cover high nutritional needs (notably milk and rapid growth). But as their digestion quickly leads to changes in the ruminal ecosystem (notably acidification), fiber digestion capacity decreases rapidly. This creates conditions that demotivate the animal from ingesting fibrous forages and tend to prove that ingested fiber does not cover the animals' nutritional needs.

To break this vicious circle, it is necessary to change the view on fiber value and manage feeding to effectively allow animals to produce their energy from fiber.

Managing rations with or without supplementation?

Some farmers succeed in achieving production goals without or with very little supplementation. Grazing is prioritized, as well as hay when necessary, and management techniques are enhanced to postpone as much as possible the use of costly forages or cultivated feeds.

Autres fiches Pâtur’Ajuste

- Choisir ses pratiques de fauche

- Concevoir la conduite technique d'un pâturage

- Façonner les caractéristiques de la végétation à une saison donnée

- Reconstituer « naturellement » un couvert prairial

- Saisonnaliser sa conduite au pâturage

- Clarifier ses objectifs en pâturage

- Réussir sa mise à l'herbe en pâturage

- L'ingestion au pâturage

- Connaître en renforcer la digestion de la fibre en pâturage

- Les refus au pâturage

- Faire évoluer la végétation par les pratiques en pâturage

- Préférences alimentaires au pâturage

- Bagages génétiques et apprentissages en pâturage

- Le report sur pied des végétations en pâturage

- Préciser ses pratiques de pâturage

- Evaluer le résultat de ses pratiques de pâturage

- Mieux connaître ses végétations en pâturage

- Mieux connaître ses animaux de pâturage

- Les ressources ligneuses en pâturage

Sources:

SCOPELA, with the contribution of farmers. Technical sheet from the Pâtur’Ajuste network: Knowing and strengthening fiber digestion. November 2019. Available at: https://www.paturajuste.fr/parlons-technique/ressource/ressources-generiques/connaitre-et-renforcer-la-digestion-de-la-fibre