Understanding and Avoiding Nitrogen Hunger

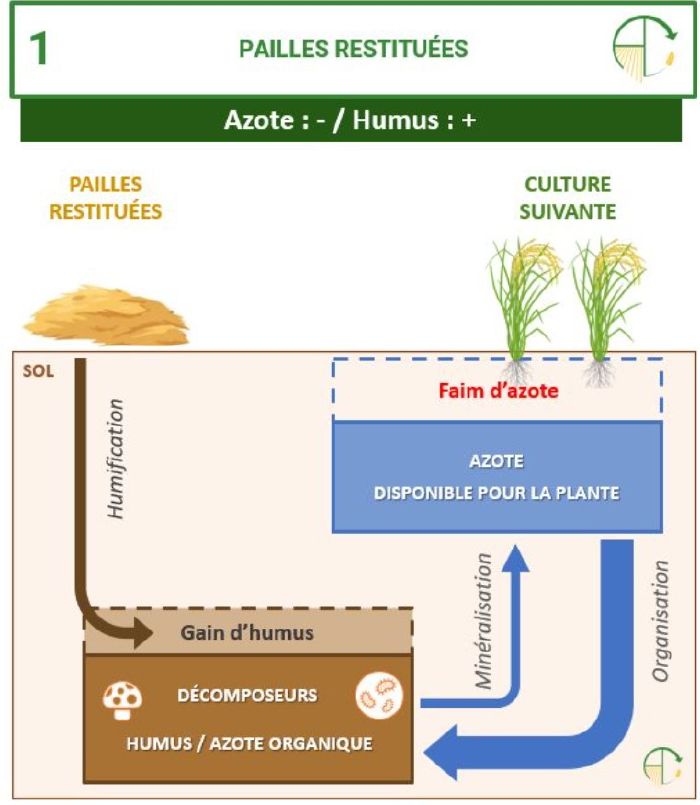

The phenomenon of "nitrogen hunger" manifests as weakening of plants, growth delay and/or leaf discoloration. It occurs when the soil is too rich in carbon compared to nitrogen, which can be caused by certain inputs of organic matter (straw or RCW for example).

What is nitrogen hunger?

Mechanism

Nitrogen hunger is caused by competition between soil microorganisms and plants for inorganic nitrogen.

This inorganic nitrogen is produced by soil microorganisms (bacteria and fungi) from the organic nitrogen contained in crop residues and animal droppings for example. Plants need it for their growth and are able to assimilate it in the form of nitrates (NO3-) and to a lesser extent in the form of ammonium (NH4+).

However, to grow, multiply, and produce the enzymes necessary for the decomposition of carbon molecules, soil microorganisms also consume inorganic nitrogen. In the case of a cereal straw crop, they use on average 4g of nitrogen for 100g of carbon[1]. So if organic matter with a C/N ratio (carbon/nitrogen) much higher than 25/1 is added, the multiplication of microorganisms is stimulated by the large amount of carbon, and they will take nitrogen from the soil instead of releasing it.

There is then competition between microorganisms and plants for inorganic nitrogen, even nitrogen shortage in the soil, which causes the cessation of plant growth and their yellowing. It is also possible that all the nitrogen in the soil is unavailable and in this case the development of bacteria also stops.

This soil depletion is temporary because it is only a nitrogen immobilization in microorganisms. Nitrogen is not lacking in the soil but it is not available. However, by respiration, microorganisms release CO2 while retaining their nitrogen. The C/N ratio therefore eventually decreases. Moreover, when all the added organic matter is decomposed, a large part of the microorganisms die and release the nitrogen they had absorbed. However, the enzymes released into the soil by bacteria to digest organic matter can remain active even after the death of the bacteria.

The duration of nitrogen unavailability depends on the materials added, their burial depth, the type of soil, its structure, and the climate. Although it can range from a few days to several years, many speak of an average duration of 6 months [2][3], which could be explained by the half-life of most bacterial substances being about 6 months. The main factor influencing the speed of nitrogen mineralization is however the soil albedo which determines its temperature. On an irrigated plot in summer (thus humid and warm), nitrogen hunger lasts no more than fifteen days.

Aggravating circumstances

The effect of nitrogen hunger is favored by conditions unfavorable to the mineralization of organic matter :

- cold soil,

- acid soil,

- hydromorphic soil (excess water).

For example, in March the soil is still cold and its microfauna is not active. Straw added at this time will not be decomposed and mineralized and will even slow down soil warming. The amount of nitrogen available in the soil for the next crop will therefore be reduced.

The phenomenon is also more significant if the organic matter is shredded and buried than if it is simply spread on the soil.

Effects

These are simply those of a nitrogen deficiency thus : cessation or slowing of growth, weakening, yellowish to white leaves.

For plants with low nitrogen demand, such as lettuces, onions, there will probably be no effect on crop growth. For legumes the effects are also reduced but less clear. These plants mainly need soil nitrogen after emergence and before the establishment of nodules allowing atmospheric nitrogen fixation (which occurs from 235 degree days[4]). The presence of nitrogen residues in the soil during this transitional period favors the future establishment of nodules, but an excess (more than 50kg/ha[4]) delays it.

How to avoid nitrogen hunger?

However, mulching should not be stopped as it is very useful for humus formation, retains soil moisture, and limits weed development.

Optimize your fertilization:

- Align inputs with plant needs, its fertilizer use efficiency and soil availability (importance of measuring).

- To closely match the needs of crops, the use of DSS (Decision Support Tools) simple and functional can quickly pay off.

- Cover crops are an important source of assimilable organic nitrogen and potential fertilizer savings.

It is better to fertilize in two stages :

- Apply carbon-rich material (straw, RCW) well in advance, at the end of summer after a winter crop for example, and let the digestion flora transform this material into humus.

- Apply before sowing in spring tender biomass with a low C/N ratio : green hay rich in legumes, compost, etc. Mineral nitrogen fertilizers can also be used as starter or shortly after sowing. Materials such as ground horn, clippings, nettle or comfrey leaves, and kitchen green waste can be used in gardening or market gardening but are hardly feasible on large areas due to the quantities required and their high cost.

- Increase monitoring and measurements to detect needs.

Other avenues are :

- Choose the date of mulching and sowing well, to allow time for microorganisms to decompose plant residues and mineralize nitrogen before crop development. So in autumn when plant needs are low, or in spring when the soil is already well warmed.

- Choose amendments balanced in carbon and nitrogen : C/N between 15 and 35, ideally equal to 25 (see “C/N ratio of some amendments”). Mature composts or manures are useful in this case, however it should not be forgotten that "maturation" means emissions of CO2 and methane, and thus as much carbon lost to the atmosphere when it would have been very beneficial as humus.

- Place plant residues on the soil surface without burying them allows slower and more spread assimilation of carbon, and reduces the risk of nitrogen hunger, even with RCW or fresh straw. They can be incorporated into the soil to 2 or 3 cm provided good aeration.

- Promote the activity of nitrogen-fixing bacteria by ensuring sufficient sulfur and trace elements in the soil.

- Promote overall soil life, especially fungi. They digest coarse organic matter and lower its C/N ratio in the process and make it available to earthworms and the rest of the macrofauna. They thus accomplish the first step of decomposition. Some soil bacteria also fulfill this role, but fungi have the particularity of being much more nitrogen-efficient and therefore do not create nitrogen hunger. These fungi develop well on plant residues that are slightly moist and well oxygenated.

C/N ratios of some amendments [5]

| Product | C/N ratio |

|---|---|

| Urine | 0.7 |

| Manure leachate | 1.9 - 3.1 |

| Mixed slaughterhouse waste | 2 |

| Blood | 2 |

| Green plant materials | 7 |

| Humus, black earth | 10 |

| Manure compost after

eight months of fermentation |

10 |

| Grass | 10 |

| Comfrey | 10 |

| Poultry droppings | 10 |

| Domestic animal droppings | 15 |

| Mature manure compost,

4 months, without soil addition |

15 |

| Farm manure after

3 months storage |

15 |

| Legume hay | 15 |

| Alfalfa | 16 - 20 |

| Fresh manure poor in straw | 20 |

| Kitchen waste | 10-25 |

| Potato haulms | 25 |

| Urban compost | 34 |

| Pine needles | 30 |

| Fresh farm manure with

abundant straw |

30 |

| Black peat | 30 |

| Tree leaves (at fall) | 20-60 |

| Green plant waste | 20-60 |

| Blonde peat | 50 |

| Cereal straw | 50 - 150 |

| Oat straw | 50 |

| Rye straw | 65 |

| Ramial chipped wood

(chipped branches) (depending on wood type and chip diameter) |

60 - 150 |

| Bark | 100-150 |

| Wheat straw | 150 |

| Paper | 150 |

| Decomposed wood sawdust | 200 |

| Hardwood sawdust

(young leaves) (average) |

150 - 500 |

Note :

- According to the Chamber of Agriculture of Pyrénées-Orientales, horse manure would systematically cause nitrogen hunger during the first year after spreading[6], perhaps because it often contains a lot of straw. However, there are not enough studies on the subject.

- Composting materials too rich in carbon before spreading them has the effect of lowering their C/N ratio.

Example of use in market gardening :

Mix 2 wheelbarrows of grass (C/N = 10) with 1 wheelbarrow of chipped branches (C/N = 70) :

Average ratio (Rm)= (2 * 10 + 1 * 70)/3 = 90/3=30

WARNING : this calculation is only valid if the dry matter content (percentage of matter that is not water) is similar for the considered wastes. If not, weighting must be done based on dry matter.

To generalize :

Rm = (n1*R1 + n2*R2 + n3*R3)/(n1+ n2 + n3)

With Rm the average ratio, n1 and n2 the respective quantities of components and R1 and R2 the C/N ratios of these components.

How to correct nitrogen hunger?

If it is too late for preventive measures, it is possible to correct nitrogen hunger with quickly assimilable nitrogen fertilizers.

On very small areas or in vegetable gardens, organic fertilizers (more expensive) can be considered:

- nettle or comfrey leaf

- dried horn

- castor cake

- guano

- …

Should nitrogen hunger be corrected?

If your goal is to enrich the soil in nitrogen for your next crop, avoid inputs of organic matter too rich in carbon, as mentioned above. But the addition of carbon-rich matter allows among other things to improve the humus content, its stability and soil structure. So it all depends on your needs and objectives.

Moreover, in the conference Nitrogen at will - nitrogen hunger and nitrogen-fixing bacteria, François Mulet estimates that the very large quantity of RCW applied over several years caused the fixation of thousands of nitrogen units in his soils in the long term. This also caused nitrogen hunger of 5 to 6 months at the beginning, but ultimately it was, according to him, very beneficial for the fertility of his soils.

Sources

- Dubus Gilles (April 9, 2021), "Nitrogen hunger - Causes and solutions", The Organic Gardener's Blog https://www.un-jardin-bio.com/faim-azote/

- "How we definitively overcame nitrogen hunger", Ferme de Cagnolle https://fermedecagnolle.fr/agronomie-et-msv/agro-ecologie/comment-on-a-vaincu-la-faim-dazote/

- "C/N ratio", https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rapport_C/N?oldid=114515582

- Michonnet Jean-Luc (2015) "Hydromorphic soils and wetlands", SOLAG n°5, 01/06/2015 https://pays-de-la-loire.chambres-agriculture.fr/fileadmin/user_upload/Pays_de_la_Loire/022_Inst-Pays-de-la-loire/Listes-affichage-FE/RetD/Vegetal/Bulletins-SOLAG/Physico-chimie_du_sol/20150601_SOLAG_Sols_hydromorphes_et_zones_humides.pdf

- ↑ "Nitrogen hunger: what is it? How to avoid and remedy it?", (2021), Promesse de Fleur https://www.promessedefleurs.com/conseil-plantes-jardin/ficheconseil/la-faim-dazote-quest-ce-que-cest-comment-leviter-y-remedier

- ↑ https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Faim_d'azote

- ↑ [[Nitrogen at will - nitrogen hunger and nitrogen-fixing bacteria - François MULET]]

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Maé Guinet, Bernard Nicolardot, Vincent Durey, Cécile Revellin, Frédéric Lombard, et al.. Symbiotic nitrogen fixation and previous effect: are all seed legumes equal?. Innovations Agronomiques, INRAE, 2019, 74, pp.55-68. ff10.15454/jj5qvvff. ffhal-02158172f https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02158172/document

- ↑ https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rapport_C/N

- ↑ Anne Sandre, Chambre d’Agriculture des P-O, Viticulture Service https://po.chambre-agriculture.fr/fileadmin/user_upload/Occitanie/073_Inst-Pyrenees-Orientales/IMAGES/PRODUCTIONS_TECHNIQUES/VITI/Fertilisation_d_entretien_du_sol_en_viti/Fiche-AZOTE_nv.pdf