Organic residual products

While they are a source of complementary organic matters to boost biological activity and soil properties, organic residual products are nonetheless a means to provide additional mineral elements including, among others, nitrogen. However, although it is logical to consider them as fertilizing products, these organic matters will never be fertilizers. Between products with rather fertilizing value or rather amending value, the subtlety lies in knowing where to place the cursor.[2]

What is an organic residual product (ORP)?

Definition

The soil is like a vehicle. To function properly, it needs three things:

- A fuel: the soil organic matters (SOM).

- An engine: the microbial biomass (MB).

- A transmission: the activities of this biomass.

The role of the farmer is summarized as providing a quality and continuous fuel, necessary for his "soil-vehicle" to deliver its full power and, on the other hand, to protect this whole system.

We distinguish organic residual products (ORP) from soil organic matters because they are external to the soil. They include all organic products of urban, industrial, or agricultural origin, whether treated or not (WWTP sludge, composts, agro-industrial effluents, livestock effluents, digestates, RCW,…).

Origin of ORP

Livestock effluents represent the most abundant source of organic residual products with an annual mass of about 275 million tonnes of raw material, composed of 86% manure.

In comparison, agro-industrial organic waste represents 43 million tonnes, WWTP sludge 9 million (mostly agricultural products sent to cities and which should normally be redistributed to fields), and composts from green waste, biowaste, and household waste less than 2 million tonnes. It should be understood that important mineral flows transit with this organic matter, primarily nitrogen but also P, K, etc.

ISMO and C/N, two characteristics of ORP

The C/N ratio, often mentioned, is a good indicator of the value of an ORP. The higher the C/N, the more carbonaceous or strawy the product is and the more it has an amending value. Since this criterion is not sufficient, two measurements now allow better characterization or "profiling" of an ORP:

- The ISMO (Stability Index of the organic matter), which qualifies the amending value of the product, allows to characterize the organic stability of the product or its proportion of organic matter (OM) likely to maintain the SOM stock. The higher the ISMO, the more the product helps maintain the SOM stock in the long term.

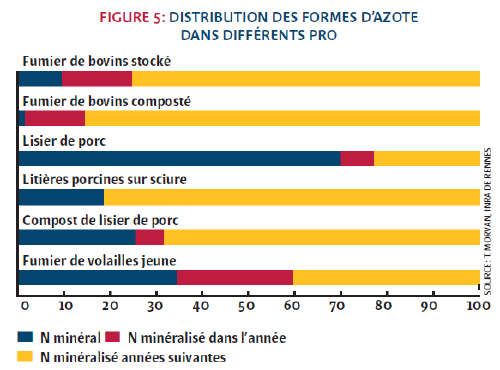

Distribution of nitrogen forms in different ORPs - The N supply of the product (nitrogen availability for plants) and thus rather its fertilizing value.

In summary, compared to situations without ORP input (only mineral fertilization), it is well proven that regular inputs of ORP (especially livestock effluents since they are mainly studied) provide, in the long term, additional mineralization via the increase of organic matters. Most trials show that this additional mineralization can supply extra annual amounts of mineralized nitrogen ranging from 25 to over 80 kg/ha (after several years of repeated inputs).

Nevertheless, within these ORPs, there is a very large variability in composition and thus effects. It is therefore better to know exactly what one wishes to use and be clear about objectives before proceeding further.

Evolution of ORP in the soil

Microbial biomass at the heart of ORP evolution

When it comes into contact with the soil, any ORP undergoes the same transformation or evolution processes as SOM and in turn becomes SOM.

The microbial biomass (MB) is at the heart of these transformations. The transformation and reorganization process of ORP in soil is as follows:

- The large constituent molecules are transformed into simpler elements. They are thus broken down, chewed, "miniaturized" to produce mineral elements that can feed soil microorganisms and plants. ORPs provide not only C, N, P, or K but are also intense suppliers of macro-elements (S, Ca, Mg) and trace elements (iron, zinc, molybdenum, copper, boron, manganese) depending on their origins.

- Not all constituent molecules of ORPs are "digested" at the same rate. Sugars are consumed first (providing the primary energy to MB), then increasingly "tough" components: hemicellulose, cellulose, then lignin.

- The smaller molecules are also reorganized into more complex ones, grouped under the generic term humus.

The very nature of the soil has little influence on these processes. However, some soil aspects and climatic conditions impact the incorporation of ORP and their transformation rate:

- Having enough clay particles to fix humic particles and thus form the clay-humus complex.

- Having an aerated soil structure with good water and oxygen circulation.

- Temperature and moisture mainly affect the transformation rate of SOM and thus MB activity, hence the existence of "mineralization seasons", mostly in spring and autumn.

- Human action impacts through cultural practices such as tillage, the crops produced, but also other practices like irrigation (when water is applied in heat, mineralization increases).

Using ORP on your farm

No need to be a livestock farmer to valorize your own ORP

All organic wastes, whatever they are (harvest residues, small straws but also non-marketable grains (separator waste)), produced on the farm can be collected and composted. Compost can be spread on long cover crops, on short intercrops (before rapeseed), or even on clover sowings, for example.

Compost is spread on the surface, without mulching, and it is possible to use a manure spreader equipped with a hood. The cost is low and the organic matter is local. The technique also avoids penalties at marketing due to the presence of "bad" grain.

Pig slurry + cattle manure : a winning duo

Being able to combine these two ORPs offers all advantages : pig slurry alone replaces mineral fertilization. It brings microbial biomass itself, stimulates it, and in addition to immediately available nitrogen, it also supplies P, K, and other trace elements. By associating cattle manure, the fertilizing inputs via slurry are complemented by amending inputs which act rather on the long term (a significant part of nitrogen is contained in stable molecules requiring more time to mineralize).

A long-term INRA trial at Rennes-Champ Noël, from the 1990s to 2000, shows that long-term yields of a corn/wheat crop sequence can be maintained by substituting mineral fertilization with pig slurry inputs. This substitution saved on average each year 100 kg/ha of N for corn and 130 kg/ha for wheat, as well as 60 kg/ha of P2O5 and 100 kg/ha of K2O.

However, it should be noted that these trials analyze the residual effect of ORP, after repeated annual inputs.

Fertilizing or amending ORP

Like SOM, ORPs have the same "global" functions on the soil:

- They act on the overall biological fertility of the soil, through the activity of its fauna and flora, by feeding it and participating in its diversity and renewal. In the end, they contribute to plant nutrition (inputs, storage, and diffuse availability of various nutrients).

- They also positively affect soil organization and its structuring properties, aeration, water efficiency, and stability.

However, not all ORPs are alike. Their impact on the soil-plant system will therefore differ and their use will be different. Their composition and thus evolution depend on multiple parameters : type of animals raised, feeding, prophylaxis, rearing conditions, type of bedding

It is useful to categorize these products, and two main types of ORP can be distinguished :

- ORPs with rather fertilizing value provide their energy and readily available nitrogen quite quickly for microorganisms and plants. They generally degrade fairly rapidly and thus have rather short/medium-term impact, hence the usage of the term "fertilizer" to identify them. Livestock effluents with little straw, such as slurry, or products from low-carbon agro-industrial transformations, can belong to this category.

- ORPs with rather amending value provide elements over the longer term because they are mainly composed of larger molecules requiring more time (more than a year) to mineralize. They contribute to a longer residence time of organic carbon and thus nitrogen.

Tillage, chemical fertilizer, irrigation have a positive effect on mineralization, masking the potential depressive effect of ORP on nitrogen. In no-till, tillage, a mineralization factor, is lost and the preemptions of ORP, which occur exclusively on the soil surface where sowing takes place, are no longer masked. In no-till, it is therefore even more important to know what ORP is used and how.

Risk of immediate depressive effect

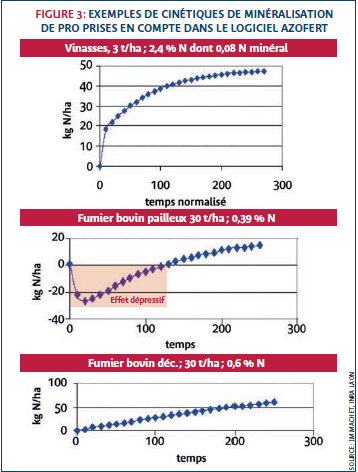

Different ORPs do not have the same nitrogen mineralization rate. In these graphs, we see the mineralization kinetics of 3 ORPs : vinasses and two cattle manures, one of which is strawy. The main takeaway from these three kinetics is their overall shape.

Vinasses, for example, correspond to an ORP that provides nitrogen very quickly available for soil and plants. Cattle manure can also behave similarly, although with a slower mineralization rate at the very beginning of its transformation.

When the manure becomes more strawy (richer in carbon because richer in cellulose), the kinetics change significantly. The ORP even becomes, from the start of its evolution in the soil, a nitrogen consumer. This is the curve that dips down in the first weeks. This state is temporary and, after this effect passes, the ORP becomes a nitrogen supplier again. Researchers call this a "depressive" effect. The organic product is very carbonaceous and there is not enough rapidly available nitrogen in the product for the needs of the degrading microflora and MB will, in the first weeks, draw mineral nitrogen from the soil to attack the degradable carbon (soluble sugars, hemicelluloses, cellulose) contained in the product.

Thus, livestock effluents are not always fertilizers, at least not always initially. Such ORPs should be applied well before the nitrogen needs of a crop, allowing time for them to evolve and become net nitrogen suppliers rather than nitrogen consumers.

ORP and cover crops

Cover crops are complementary to ORPs because they compensate for the "defects" of ORPs. It is difficult to predict the behavior of most ORPs in the field. One can predict whether they tend to be fertilizing or amending but what characterizes them above all is their great variability and even unpredictability. Cover crops, on the other hand, and once mixtures of different and varied plant families are sown, seem more "stable" and predictable.

The transition period from a soil to conservation agriculture (CA) is always delicate. It is then good to help it acquire a more substantial organic status thanks to ORPs. But not just any ORPs: for a good start in CA, it is better to choose highly fermentable ORPs, rich in fast nitrogen, precisely to compensate for nitrogen hunger problems.

Products of more amending nature, such as composts, can come in a second phase, during the so-called "cruise" period. They will help maintain the system and continue to progress without risks. In this case, the mulch acquired on the surface will provide biological activity with energy and nitrogen and compensate for the imbalances of ORPs for more complete and faster digestion and incorporation, always without shocks.

Cover crops also have another effect regarding ORPs: they attenuate some of their environmental drawbacks such as the risks of volatilization and other element losses into the environment. Beware of ORPs that tend to draw nitrogen in the early stages of their degradation, as they could potentially hinder the good development of the cover crop.

When to spread?

Spreading mainly depends on the nature of the ORP.

- If it is rather of fertilizing nature like slurry, it is better to apply it slightly before the plants' needs because it is not a fertilizer!

- If, on the contrary, it has more of an amending value like strawy manure or green waste composts, it is better to apply it well before the needs so that it starts its digestion and especially to avoid nitrogen preemption risks. This type of ORP can indeed tend to withdraw nitrogen from the soil in the early stages, which can be very detrimental to the crop. This effect is only temporary and, after some time, its degradation becomes a supplier of elements (always diffusely).

Taking advantage of the presence of the cover crop to spread effluents has advantages :

- At the soil level, organic matter transformations are long, dependent on the base product, and strongly influenced by weather conditions. It is therefore preferable to anticipate and allow biological activity time to digest the product to obtain a larger assimilable portion for the following crop.

- Soluble elements, including nitrogen, will be quickly mobilized by the existing vegetation, thus limiting leakage risks. Moreover, this slight fertilization will boost the cover in autumn with a notable gain in biomass production.

- The cover has already rooted, it is established and deep. It will therefore be little impacted by potential nitrogen preemptions on the soil surface by the ORP.

- The biological activity that restarts intensely with autumn rains will find in this input a choice food that it will assimilate and incorporate into the soil with other residues. Better quantity and quality feeding also guarantees more work and thus better biological structuring the following spring.

- Spreading in an established cover in autumn when moisture returns is also an effective way, much more than any incorporation, to limit losses by volatilization which can sometimes be quite significant. It is therefore a way to conserve more nitrogen in the system but also to limit odor nuisances and greenhouse gas emissions.

- Driving on plots with machinery that are increasingly heavy in spring generates compactions, which even if intensively worked remain penalizing for the following crop. Thus, spreading in autumn also preserves soil structure which is generally, unlike spring, dry at depth and better supports tool traffic. Soils will be less impacted by this traffic as they are colonized by extensive root systems which play the same role as reinforcement in concrete. Finally, if the structure is slightly damaged under a wheel passage, biological activity has several months to intervene and correct the situation.

- Finally, for all those practicing Simplified cropping techniques (TCS) and direct seeding (DS) as well as conventional farmers, letting a manure or even a thick slurry evolve for several months on the soil surface also greatly reduces the risk of mainly spreading weed seeds which will be consumed by decomposition biological activity or ferment while knowing that seedlings will be destroyed before the establishment of the next crop.

Caution with incorporation

Incorporating a highly carbonaceous SOM at the soil surface leads to a significant nitrogen uptake despite the mineralization triggered by tillage, a momentarily dangerous situation for the crop. On the other hand, placing SOM on the soil surface within vegetation and cover crops (to limit volatilization and ensure permanent moisture for continuous evolution) limits the risks of nitrogen preemption.

In conservation agriculture, it is beneficial to add SOM, as they increase organic return and boost biological activity and soil structuring. It is a way to provide complementary and overall fertilization. It is essential to accept that the system is fed first and that the mineral return time for crops is necessarily long.

Contrary to common belief, it is better to seek more readily available nitrogen to compensate for the lack of mineralization induced by significant cover crops and the reduction or elimination of tillage. Once self-fertility has evolved, it is then possible to use more carbonaceous SOM.

Conclusion

Using SOM raises many questions:

- What do I expect from the addition of organic matter?

- Where am I in my conservation agriculture approach?

- What is the status of my soil, what is its organic level?

- Is it capable of digesting what I might bring to it?

- Which SOM do I have access to?

- What are their characteristics, advantages, and drawbacks?

SOM are an additional source of mineralization. The first SOM to use are crop residues and cover crops which ensure regular maintenance of soil biological activity. But a single organic source cannot fulfill all the desired functions (physical, chemical, and biological). Therefore, there is no single SOM for every answer.

Cover crops all the time (especially when the soil is in transition and does not yet have a high organic level) and varied and sufficient SOM inputs, initially more fertilizing in nature.

It will then be time to add more carbon to the soil via more amending SOM such as composts until it is even possible to do without them. The goal is always to reach, on average, autonomy, where the system no longer needs external help.

Finally, fertilization with SOM cannot be precisely managed. Thanks to them, the system is better nourished, progress is made toward self-fertility, but it is impossible to predict exactly what they provide and when, because their functioning depends on far too many parameters, primarily climate.

Sources

- ↑ Arvalis, 2018: What happens to the nitrogen in organic residual products? https://www.terre-net.fr/arvalis/article/142965/que-devient-l-azote-des-produits-residuaires-organiques

- ↑ TCS, 2013 : EFFLUENTS, COMPOSTS AND OTHER ORGANIC RESIDUAL PRODUCTS : TRUTHS AND DISILLUSIONS https://agriculture-de-conservation.com/sites/agriculture-de-conservation.com/IMG/pdf/matieres-organiques-tcs-72.pdf