How Soil Organic Matter Forms, Stabilizes, and Is Mineralized

We believe we know a lot about the composition and fate of soil organic matter. The term humus, for example, is widely used, perhaps incorrectly. Here are the latest scientific advances on the subject. The persistence of organic matter[1] in soils (SOM) was explained solely by their chemical composition until the 1990s-2000s. A long-established theory suggested that SOM could be classified according to their chemical composition which sometimes made them impossible to degrade by microorganisms (bacteria, fungi). According to this concept, the richer the plant residues were in lignin, the harder they were to degrade and the more they contributed to the persistent SOM stock.

New laboratory techniques have allowed the observation, labeling, and tracing of carbon in plants, soil organisms, soil microaggregates, and CO2. It has been demonstrated that microorganisms are capable of decomposing all types of SOM (except charcoals). For example, lignin can be easily degraded by microorganisms provided that carbon is bioavailable in the environment as an energy source. These new techniques have helped understand that the persistence of SOM depends on interactions between plants, microorganisms, and soil minerals. Over time, evidence has accumulated that the soil matrix protects from decomposition various plant-derived molecules, but also many small organic molecules of microbial origin.

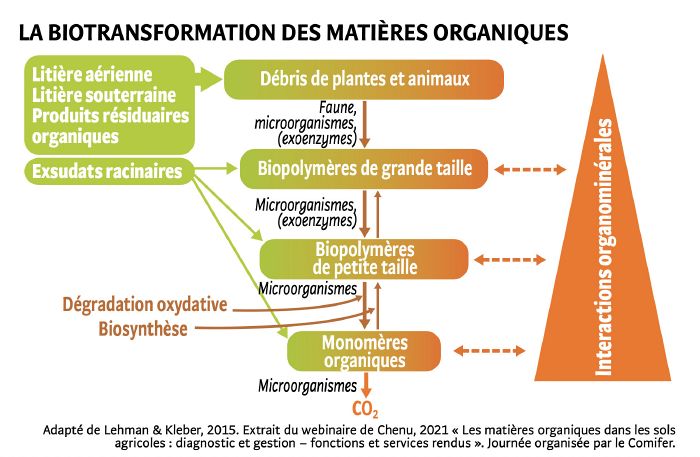

Fresh organic matter (crop residues, cover crops, and organic products) added to the soil is decomposed by macrofauna (earthworms, insects), mesofauna (microarthropods such as springtails), and soil microorganisms.

Soil organic matter is a continuum

The soil fauna's role in SOM dynamics will not be discussed here. Their effect on organic matter decomposition is proven; however, much remains to be understood on this subject. The recent increase in research projects on this topic should help better understand the relative importance of these still under-studied organisms internationally.

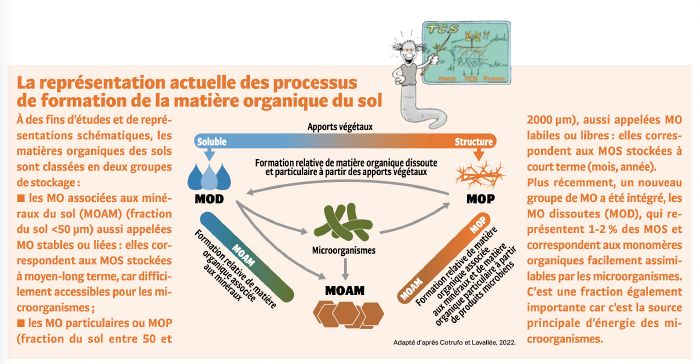

Microorganisms play a predominant role in organic matter dynamics. They secrete enzymes that degrade plant cell walls into increasingly smaller organic molecules (biopolymers of various sizes) until their reduction to organic monomers.

At the end of the chain, organic monomers are small soluble molecules whose size (about 1 nanometer) makes them assimilable and metabolizable by microorganisms into CO2. Regardless of their size, organic molecules can interact and be stabilized in the soil through aggregation with soil minerals. This is why scientists now describe SOM as a continuum. Moreover, the smaller the size of organic molecules, the more soluble in water, reactive, and rapidly adsorbed onto soil minerals (notably clays) to form organomineral complexes (updated name for the clay-humus complex). The living biomass of soil organisms constitutes a temporary stock of organic matter (<~5% of total soil organic carbon). Dead microorganisms (necromass) and metabolites from microbial activities are then partly complexed to mineral particles. Contrary to previous beliefs, these microbial-derived molecules do not always have the fastest turnover. These microbial molecules significantly feed the most persistent/stable fraction of SOM (see box and graph below). Several recent publications converge on the fact that microorganisms are responsible for a large part of the stable organic matter in soil. Nearly 50% of SOM would come from microbial necromass (Liang et al., 2019).

Influence of climate and soil types

The SOM stock increases when SOM inputs exceed outputs by mineralization. But what limits mineralization?

Climate is the main factor controlling SOM output levels by mineralization. Contexts of very low temperatures, too low oxygen levels (anaerobic), or too low moisture (severe droughts) indeed limit microorganisms.

SOM persistence is also the result of chemical protection sometimes combined with physical protection that makes SOM less accessible, or even inaccessible to microorganisms. Chemical protection corresponds to the adsorption of SOM onto soil mineral particles (notably clays) or their complexation with elements such as iron or calcium. Adsorption and complexation make SOM more recalcitrant, i.e., harder to catabolize by enzymes secreted by microorganisms. Microbial activity can also be limited by a physical barrier preventing enzymes from accessing protected organic matter within small pores in organomineral aggregates. Most of the physically protected SOM would be found in soil fractions <50 μm. Well protected, it could persist there for several centuries and be less vulnerable to environmental changes.

These access constraints for enzymes depend on soil types and the capacity of soil minerals to form strong organomineral bonds. Thus, the potential for SOM protection differs with soil type, notably with the nature and composition of soil minerals.

Besides climate, microbial activity is controlled by energy and nutrients availability.. This availability controls both the rate and efficiency of SOM mineralization.

The simpler the biochemical nature of organic residues, the easier they are to degrade for microorganisms. They represent an interesting energy return on investment for microorganisms. This is the case for residues low in lignin, having low C/O or C/H content ratios. Moreover, carbon chemistry and nutrient deficiencies (nitrogen, phosphorus, sulfur) are recognized as a major microbial limitation factor for SOM decomposition and soil carbon storage. This is explained by lower C/nutrient content ratios in microorganisms than in plants.

Thus, MOM (Mineral-Associated Organic Matter = stable or bound OM) would preferentially incorporate SOM efficiently processed by microorganisms, i.e., derived from high-quality plant inputs. These high-quality residues have a low C/N ratio and low lignin content. This is the case for crops or cover crops of legumes used in arable farming.

In nutrient-poor soils, characterized by a low C/N ratio, nitrogen limitation can also promote mineralization of stable SOM, known as the priming effect.

Biomass added to soil promotes SOM storage

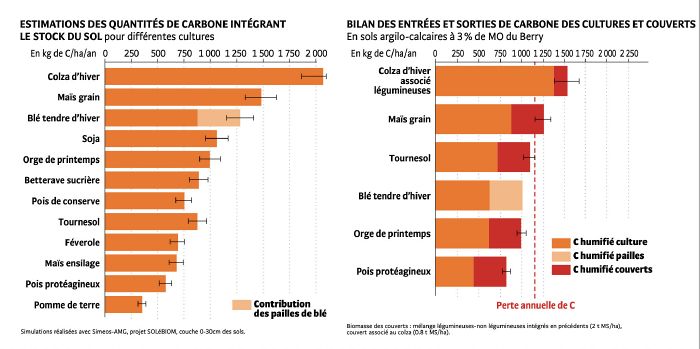

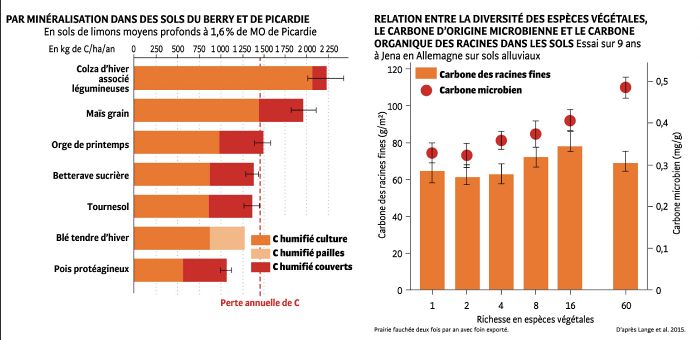

The quantities of plant residues returned to the soil, as well as exogenous organic products (manure, compost), remain the main factor favoring SOM storage. The graph above shows the contributions to the C stock from residues of various annual crops. Rapeseed and maize are the crops with the best C storage yield. Whether or not wheat straw is returned strongly impacts its contribution to the stock.

C inputs from crop residues, as well as outputs by mineralization, depend on the pedoclimate. For example, for the clay-limestone soils of Berry with 3% SOM, C outputs by mineralization (annual C loss) are lower than for the deep medium loam soils of Picardy with 1.6% SOM. Yields and thus C returns by crops are lower in Berry. In both contexts, the contribution of intercrop cover crops of 2 tons of dry matter per hectare is essential and sometimes even insufficient to compensate for annual C losses.Low C/N crops store better

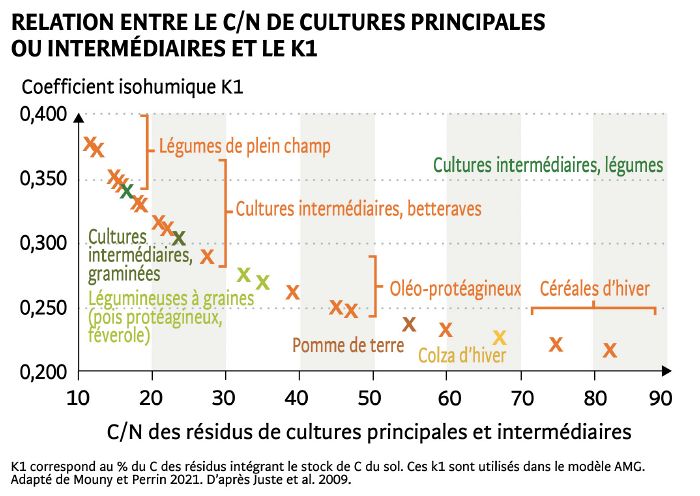

The C/N ratio of cover crops and crops has a significant impact on SOM storage. The proportion of C from plant residues integrating the soil stock was determined by Inrae through incubations of crop residues with soil under controlled conditions for 168 days[2]. Contrary to popular belief, the lower the C/N of plant residues, the higher the proportion of residue C feeding the soil C stock (K1, isohumic coefficient also called humification coefficient, high).

The proportion of C integrating the stock is higher for legumes than for cereals. But since their biomass is lower, legumes contribute less to storage.

Regarding cover crop composition, 2 tons of dry matter:

- of covers based on legumes and non-legumes feed the soil stock with 0.35 tons of carbon.

- of crucifer covers provide 0.32 tons of C

- of wheat contribute to the stock with 0.2 tons of C.

Roots and plant diversity

Rhizodeposition, which corresponds to detached root cells, dead tissues, and root exudates would represent 20% to 40% of C from photosynthesis. Root carbon would be more stable than that of aerial parts (about 2 to 3 times more). These observations have several explanations. In the upper soil layer, root-derived C stimulates microbial biomass development and thus microbial-origin OM inputs. Moreover, bacterial and fungal activity promotes aggregation of SOM with soil minerals and thus potentially their stabilization. Deeper in the soil, conditions are less favorable for microbial development and mineralization activity due to lower oxygen concentrations, lower temperatures, and lack of nutrient resources. Thus, SOM persists longer below the arable soil layer.

Plant diversity would also have a positive effect on C storage. This has been observed in various experiments in grasslands. One study notably observed an increase in biomass and fine root C along with plant species richness, and microbial C inputs. A positive relationship was demonstrated between increased rhizodeposition, microbial growth and activity, and C storage in soils, alongside plant species richness. In this study, the increase in C storage benefited the persistent/stable soil carbon pool.

Working on a long timescale

To summarize the current state of knowledge, the quantities of organic matter returned to the soil are the main factor in SOM storage. Root biomasses play a more important role than previously assumed, notably linked to their positive effect on microorganisms and SOM storage. Increasing microbial growth and activity influences both mineralization and the increase of stable SOM stock in soil. Contrary to previous assumptions, SOM derived from microbial necromass would indeed be preferentially stored in the stable soil pool. Moreover, root C at depth persists longer in the soil.

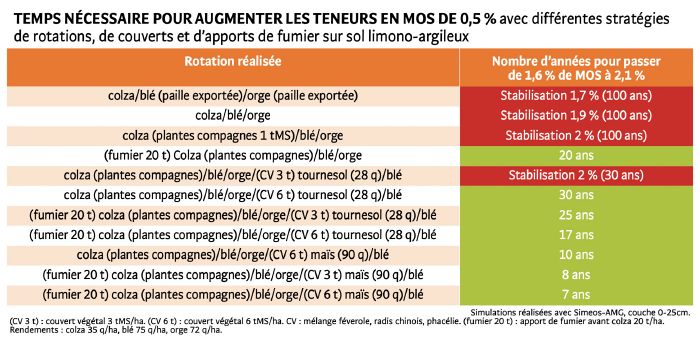

Increasing soil SOM stock requires working on a long timescale. In situations where exogenous organic matter inputs (e.g., manure) are not possible, it is essential to maximize plant biomass, notably with cover crops and high biomass crops (such as rapeseed and maize). Diversifying both cover crops and crop rotations also seems a good strategy.

Simulating SOM stock evolution

- Simeos-AMG is based on the AMG research model, which is the reference model in France for simulating soil organic matter stock evolution.

- Go here: https://simeos- amg.org to perform simulations for free.

Sources

- Original article on TCS: https://agriculture-de-conservation.com/Comment-les-matieres-organiques-des-sols-se-forment-se-stabilisent-et-sont.html

La version initiale de cet article a été rédigée par Anne-Sophie Perrin et Michael Geloen.