Flavescence dorée

This article provides an overview of Flavescence dorée (FD), a quarantine disease of grapevine: how it spreads, how to recognize it, and which collective measures help to limit its propagation.

An incurable phytoplasma disease

Flavescence dorée is recognized as one of the most severe and damaging diseases affecting European vineyards. Classified as a quarantine organism under European regulations (Directive 2000/29/EC, A2 list), it is caused by the phytoplasma Candidatus Phytoplasma vitis and transmitted by Scaphoideus titanus, the Flavescence dorée leafhopper [1].

This phytoplasma is a wall-less bacterium that lives and multiplies exclusively within the phloem of grapevine. By disrupting the transport of assimilates, it blocks the plant’s metabolic exchanges and leads to progressive decline, often resulting in the complete death of the vine.

First reported in the 1950s in the Armagnac region of southwestern France, Flavescence dorée is now present in at least 18 European countries, including France, Italy, Spain and Switzerland [2][3].

Situation in France

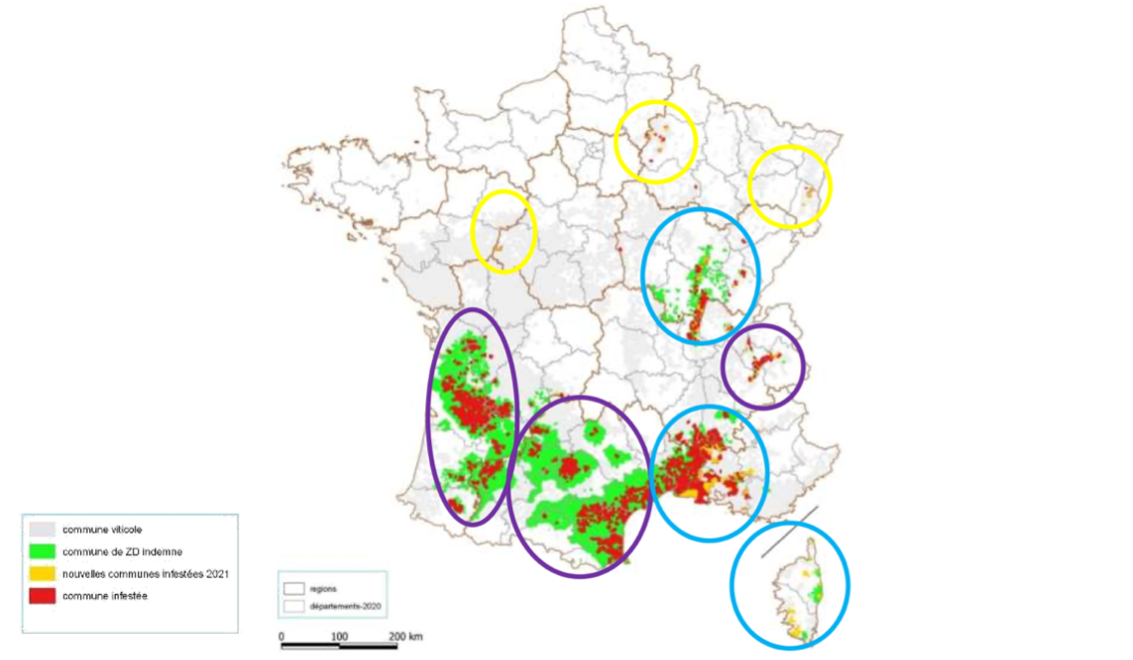

In France, the situation of Flavescence dorée varies greatly between wine-growing regions.

- Endemic areas: Nouvelle-Aquitaine, Occitanie and Savoie are persistently affected, with long-standing and recurrent outbreaks.

- Partial presence: Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur (PACA), Corsica, Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes and Bourgogne-Franche-Comté show localized outbreaks that emerged in the 2000s.

- Recent outbreaks: Champagne and the Loire Valley have experienced a more recent spread of the disease, while isolated cases have been reported in Alsace, where the vector Scaphoideus titanus is still absent [4].

To date, Lorraine remains the only major French wine-growing region with no confirmed detections.

From one season to the next, monitoring reveals a wave-like dynamic, with new outbreaks appearing at the edges of already contaminated zones.

In the Loire Valley, the contaminated surface increased from 56 to 78 plots between 2022 and 2023, despite the uprooting of infected vines and the implementation of a coordinated action plan managed by the Plant Health Organizations (OVS – FREDON, Polleniz) and regional wine federations [4].

Main vector: Scaphoideus titanus

The primary agent responsible for the epidemic transmission of Flavescence dorée from vine to vine is the Flavescence dorée leafhopper (Scaphoideus titanus). This insect, native to North America, was accidentally introduced into Europe, most likely through the importation of American rootstocks in the early 20th century.

Scaphoideus titanus is a univoltine species (one generation per year) and, in Europe, is strictly associated with grapevine (Vitis vinifera).

Life cycle

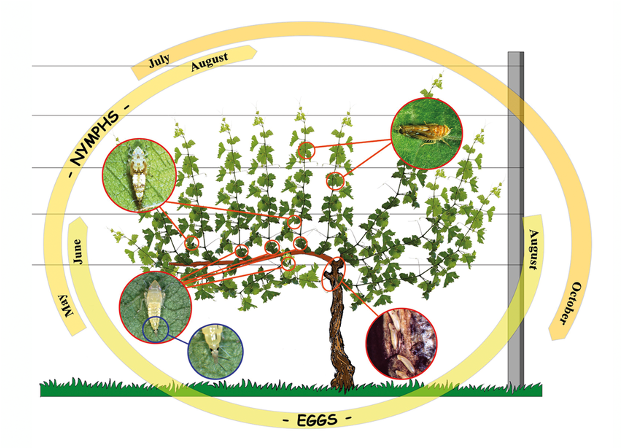

In France, Scaphoideus titanus completes its full life cycle between April and the first autumn frosts.

- Eggs: laid at the end of summer in old wood (cane internodes). They overwinter in this stage.

- Hatching: from mid-April to early May, depending on temperature.

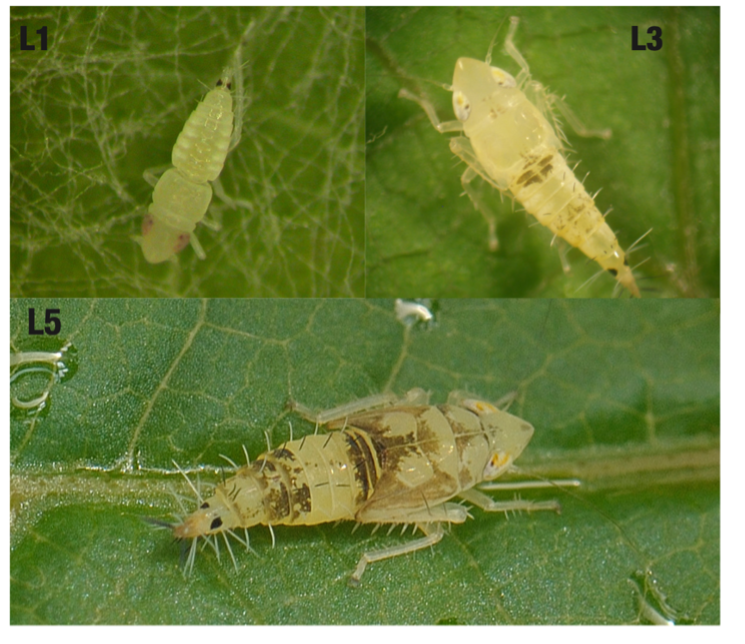

- Larvae (L1 to L5): five larval stages follow one another from May to June. Larvae cannot fly but are highly active on the foliage.

- Adults: appear from late June to July; they are capable of flight, enabling broader dispersion within the vineyard and towards neighbouring outbreaks.

- End of cycle: adults survive until the first frosts (late September–early October) [6].

Acquisition and transmission of the phytoplasma

Contamination follows a strict sequence:

- Acquisition: A healthy leafhopper becomes infected when feeding on an infected vine (stylet probing and ingestion from the phloem sap).

- Latent period (10 to 45 days depending on temperature): During this phase, the phytoplasma circulates through the haemolymph and then colonizes the salivary glands.

- Infectious insect: Once the salivary glands are colonized, the leafhopper remains infectious for life. It transmits the phytoplasma to every healthy plant on which it feeds.

- No transmission to eggs: There is no transovarial transmission. Larvae hatching in spring are always healthy, even when originating from an infected female [6].

Recognition: Key symptoms and possible confusion

Symptoms of Flavescence dorée are generally not visible during the year of infection (N) but appear the following year (N+1), or even several years later. They are most noticeable at the end of summer (late July–August).

To suspect a phytoplasma disease, growers should look for three characteristic symptoms on the same shoot.

1. On leaves:

- Discoloration: Yellowing occurs on white cultivars and reddening on red cultivars. The discoloration may be complete or partial, and sometimes follows the veins.

- Deformation: Leaves roll downward, become abnormally rigid, and feel brittle when touched.

2. On shoots

- Lack of lignification: Shoots show poor lignification (“non-ripening”). They remain green, soft and flexible (rubbery), instead of hardening and snapping like normally ripened canes.

3. On clusters

- Desiccation: Inflorescences and berries wilt and then dry out partially or completely. This can result in yield losses of up to 100%.

Because these symptoms can be confused with those caused by Bois Noir (BN), confirmation of the diagnosis relies on PCR analysis performed by an accredited laboratory, which is the only method capable of identifying ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma vitis’ [1][6][8].

Mandatory collective control: The three pillars

In France, control of Flavescence dorée is permanently mandatory across the entire national vineyard as soon as the disease is detected. The strategy is based on three coordinated components:

Ensuring the health of planting material

Using certified planting material, controlled by FranceAgriMer and the Official Certification Service (SOC), is the first barrier against Flavescence dorée. This plant material is traceable, inspected, and guaranteed free of infection before planting.

Importing plant material from other EU countries is permitted, provided it carries a phytosanitary passport compliant with Regulation (EU) 2016/2031.

To further reduce the risk of introducing the phytoplasma, nurseries apply Hot Water Treatment (HWT), which consists of immersing planting material at 50 °C for 45 minutes. Mandatory in certain regulated zones, this treatment significantly reduces the risk of transmitting the phytoplasma through planting stock [1].

Vector control (insecticide-based measures)

Control of Scaphoideus titanus is mandatory within regulated areas, previously called Périmètres de Lutte Obligatoire(PLO) and now generally referred to as Zones Délimitées (ZD).

Conventional strategy

Regulations typically require three insecticide treatments, with application dates determined each year by the regional plant health authorities (DRAAF/SRAL) according to the sanitary risk [10].

- The first treatment (T1) must be applied roughly one month after the first egg hatch, targeting the young larval stages (ideally L2–L3) before they become infectious.

- The second treatment (T2) is applied at the end of the residual activity of the first one (around 10 days after T1).

- The third treatment (T3) targets adults, if required.

In 2025, the active substances authorised in France belong mainly to the pyrethroid family.

These insecticides act by contact and aim to eliminate young larvae before they become infectious. Their performance is highly dependent on the timing of application (more effective in the evening) and on spray quality.

Biological strategy

The only plant protection products authorised against Scaphoideus titanus are natural pyrethrin and paraffinic oils, which are primarily effective on the earliest larval stages (L1–L2) [11][12][13].

Associated prophylactic measures

Early shoot removal (épamprage) must be carried out before T1, as basal shoots provide refuge zones for larvae that are poorly covered by insecticide sprays [1].

Role of GDONs

The Groupements de Défense contre les Organismes Nuisibles (GDONs) play a key role in organising this collective control strategy. Through larval counts and adult trapping, GDONs can authorise exemptions from T1 and/or T2 treatments, providing important economic and environmental benefits [14][15].

Monitoring and eradication (vine removal)

Once infected, a vine remains diseased and contagious. There is no method to cure an infected plant.

- Detection and destruction: Any vine confirmed as infected must be uprooted or destroyed, including the rootstock. The operation must be completed no later than 31 March following detection, before the vegetative restart and before larval emergence.

- If the infection rate of a plot exceeds a threshold (often set at 20% of affected vines), complete uprooting of the entire vineyard block is required.

- Rootstocks and regrowth: Rootstocks may act as symptomless carriers (infected but expressing few or no symptoms). Removal must therefore be thorough to eliminate all regrowth that could remain a reservoir for phytoplasmas.

- Wild vines: Abandoned or wild vines located within the regulated area must be removed, as they serve as refuges for the leafhopper and potential reservoirs of the phytoplasma [1].

Economic consequences and challenges

Flavescence dorée generates significant costs due to mandatory insecticide treatments, vine removal, and replanting.

Direct economic impact:

- A simulation based on data from the Occitanie region shows that, in the absence of control measures, a contaminated vineyard block may require complete uprooting within three years. This leads to substantial yield losses and high replanting and maintenance costs, severely compromising the long-term viability of the vineyard [16].

Conclusion and perspectives

Flavescence dorée remains a major threat to grapevine, and its control still relies on an essential foundation: certified planting material, coordinated monitoring, removal of infected vines, and mandatory insecticide treatments against Scaphoideus titanus. These measures are effective, but their repeated use raises concerns regarding ecological and economic sustainability.

Research efforts primarily aim to reduce dependence on insecticides. Mineral products such as kaolin show a disruptive effect on young larvae, but their efficacy remains variable [17]. Behaviour-based approaches, including vibrational or chemical signalling disruption, also offer promising avenues, although they are still at an experimental stage. In the long term, these strategies could strengthen integrated protection by improving the precision of interventions [6].

Genetic tolerance is another exploratory avenue: some cultivars appear less sensitive, but graft–rootstock interactions and the risk of asymptomatic reservoirs currently limit practical application. Marker-assisted selection could accelerate progress, but this approach remains a long-term perspective.

In the short and medium term, the most realistic advances concern the optimisation of sanitary decision-making: earlier detection of outbreaks, better-targeted interventions, and a reasoned use of physical and biological alternatives. Behaviour-based and genetic innovations will complement—rather than replace—the current core measures of disease management.

Useful links

To explore further, here is a selection of reliable and up-to-date resources on Flavescence dorée and its management in France.

A – Understanding the disease and collective control

Full webinar on the current status of Flavescence dorée in France / GDON example in Gironde – Antoine (Min 12:48–25:05)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dPOIyR9VeTk&t=376s

B – Diagnostic: accredited laboratories

Updated list of laboratories accredited for phytoplasma detection (French Ministry of Agriculture) https://agriculture.gouv.fr/laboratoires-officiels-et-reconnus-en-sante-des-vegetaux

C – Insecticides and authorised products

2025 list of authorised products (DRAAF PACA)

https://draaf.paca.agriculture.gouv.fr/modalites-de-lutte-contre-la-cicadelle-de-la-flavescence-doree-de-la-vigne-pour-a1407.html

Ephy database – conventional products

https://ephy.anses.fr/resultats_recherche/produits?f%5B%5D=usg%3A652795&f%5B%5D=usg%3A4283&uop=or&f%5B%5D=list_type_usage%3A20100401000000000001&origin=Y3VsdHVyZTE9VmlnbmUmY3VsdHVyZTI9Jm51aXNpYmxlMT1DaWNhZGVsbGVzJTIwZGUlMjBsYSUyMGZsYXZlc2NlbmNlJTIwZG9yJUMzJUE5ZSZudWlzaWJsZTI9Q2ljYWRlbGxlcyZtb2RlPSZmJTVCMCU1RD1saXN0X3R5cGVfdXNhZ2UlM0EyMDEwMDQwMTAwMDAwMDAwMDAwMQ%3D%3D

Ephy database – organic products

https://ephy.anses.fr/resultats_recherche/produits?f%5B%5D=usg%3A733159&uop=or&f%5B%5D=list_type_usage%3A20100401000000000001&origin=Y3VsdHVyZTE9VmlnbmUmY3VsdHVyZTI9Jm51aXNpYmxlMT1DaWNhZGVsbGVzJTIwZGUlMjBsYSUyMGZsYXZlc2NlbmNlJTIwZG9yJUMzJUE5ZSZudWlzaWJsZTI9Jm1vZGU9JmYlNUIwJTVEPWxpc3RfdHlwZV91c2FnZSUzQTIwMTAwNDAxMDAwMDAwMDAwMDAx

Estimated pesticide prices

https://www.coutdesfournitures.fr/sites/default/files/page_39_0.pdf

D – Regulations and official documents

DRAAF PACA – Official information on Flavescence dorée

https://draaf.paca.agriculture.gouv.fr/flavescence-doree-r37.html

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Winetwork. (2016). Guide des bonnes pratiques de gestion de la Flavescence dorée. Institut Français de la Vigne et du Vin. https://www.vignevin-occitanie.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Winetwork-projet-Guide-des-bonnes-pratiques-de-gestion-de-la-FD.pdf

- ↑ EFSA Panel on Plant Health. (2016). Risk to plant health of Flavescence dorée for the EU territory. EFSA Journal, 14(12), Article e04603. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2016.4603

- ↑ EPPO. (2022). Grapevine flavescence dorée phytoplasma – Datasheet. European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization. https://gd.eppo.int/taxon/PHYP64

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 IFV – Institut Français de la Vigne et du Vin. (2014). État des lieux de la Flavescence dorée. Techniloire. https://techniloire.com/sites/default/files/etat_des_lieux_de_la_flavescence_doree.pdf

- ↑ Dubois, A. (2023). Flavescence dorée : état des lieux et gestion territoriale [Vidéo]. GDON de Gironde, YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dPOIyR9VeTk

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 GDON de Gironde. (2023). Flavescence dorée : état des lieux et gestion territoriale [Vidéo]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dPOIyR9VeTk

- ↑ Chuche, J., & Mazzetto, F. (2024). Scaphoideus titanus up-to-the-minute: Biology, ecology, and role as a vector. Entomologia Generalis, 44(3). https://doi.org/10.1127/entomologia/2023/2597

- ↑ Ministère de l’Agriculture et de la Souveraineté alimentaire. (2024). Laboratoires officiels et reconnus en santé des végétaux. https://agriculture.gouv.fr/laboratoires-officiels-et-reconnus-en-sante-des-vegetaux

- ↑ Vitisphere. (2023). Traitement à l’eau chaude des bois et plants de vigne : une organisation bien huilée chez les pépinières Viaud. https://www.vitisphere.com/actualite-101189-traitement-a-leau-chaude-des-bois-et-plants-de-vigne-une-organisation-bien-huilee-chez-les-pepinieres-viaud.html

- ↑ DRAAF PACA. (2024). Flavescence dorée – Informations officielles. Ministère de l’Agriculture. https://draaf.paca.agriculture.gouv.fr/flavescence-doree-r37.html

- ↑ DRAAF PACA. (2025). Modalités de lutte contre la cicadelle de la Flavescence dorée de la vigne – Campagne 2025.Ministère de l’Agriculture et de la Souveraineté Alimentaire. https://draaf.paca.agriculture.gouv.fr/modalites-de-lutte-contre-la-cicadelle-de-la-flavescence-doree-de-la-vigne-pour-a1407.html

- ↑ ANSES. (2025). Base Ephy – Produits phytopharmaceutiques : usages “cicadelles de la Flavescence dorée” (conventionnels). https://ephy.anses.fr/resultats_recherche/produits?f%5B%5D=usg%3A652795&f%5B%5D=usg%3A4283&uop=or&f%5B%5D=list_type_usage%3A20100401000000000001

- ↑ ANSES. (2025). Base Ephy – Produits phytopharmaceutiques : usages “cicadelles de la Flavescence dorée” (biologiques). https://ephy.anses.fr/resultats_recherche/produits?f%5B%5D=usg%3A733159&uop=or&f%5B%5D=list_type_usage%3A20100401000000000001

- ↑ GDON de Gironde. (2023). Flavescence dorée : état des lieux et gestion territoriale [Vidéo]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dPOIyR9VeTk

- ↑ GDON des Bordeaux. (2024). Missions du GDON des Bordeaux : organisation de la surveillance et de la lutte contre la Flavescence dorée. https://www.gdon-bordeaux.fr/le-gdon/missions/

- ↑ CRAO – Chambre Régionale d’Agriculture Occitanie. (2020). Tout savoir sur la Flavescence dorée.https://occitanie.chambres-agriculture.fr/fileadmin/user_upload/265_chambre_dagriculture_-_occitanie/Interface/Doc/Publications/ToutSavoirSurLaFD-CRAO2020.pdf

- ↑ Favre, A., Mittaz, C., & Kehrli, P. (2023). Controlling Scaphoideus titanus with kaolin: Summary of four years of field trials in Switzerland (Open Access). Agroscope. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/371304680_Controlling_Scaphoideus_titanus_with_kaolin_Summary_of_four_years_of_field_trials_in_Switzerland_OPEN_ACCESS