Using Bacterial Biostimulants

Some biostimulants are developed from bacterial microorganisms known as agriculturally beneficial. These bacteria live in the rhizosphere and directly impact the soil and plants. They have been termed by the scientific community as PGPR, for Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria[1].

Description

The rhizosphere is a dense and biologically rich zone in the soil. Plants release ions and compounds through root exudations that locally disturb the soil balance. These compounds are mainly carbon molecules, including sugars, organic acids, amino acids, and phenolic acids. They attract organisms that can be beneficial, pathogenic, or neutral to the plant. It is in this environment that microorganisms establish themselves whose development strategies are closely linked to the plants with which they interact: among them are the PGPR (Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria). These bacteria present in the rhizosphere have a recognized positive effect on the plant. PGPR are capable of colonizing the root surface, surviving and multiplying there while being competitive against other microorganisms. These bacteria belong to the Rhizobium family. Generally symbiotic, for example, PGPR specialize in the nodular structures of Fabaceae.

Modes of action and benefits

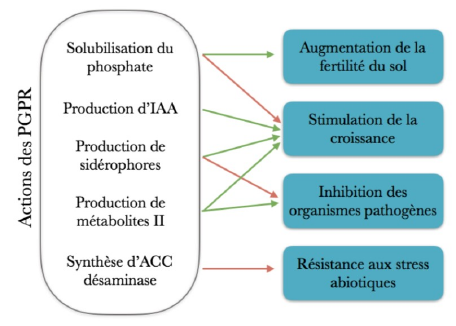

Four main effects have been identified in PGPR. They can:

- Increase the availability of nutrients,

- Regulate phytohormone production,

- Increase tolerance to abiotic stresses,

- Inhibit bioaggressors by competition.

Microorganisms used as biostimulants are applied on seeds, leaves, or soil. These microorganisms are often used in addition to “classic” fertilization, most often to reduce its use by improving efficiency.

Their modes of action vary depending on the inoculated species and the effect considered.

Increase in nutrient availability

Plant growth can be indirectly promoted by better soil fertility in basic nutrients (N, P, K) and trace elements.

Phosphorus case

Phosphorus is one of the main limiting factors for plant growth. Although present in sufficient quantity in soils, it is mostly found in insoluble forms unavailable to plants. Phosphorus solubilization is a solution to increase the concentration of P in bioavailable forms (H2PO4-, HPO42-) without exogenous mineral fertilizer input. There are bacteria capable of solubilizing inorganic phosphorus, called Phosphate-Solubilizing Bacteria (PSB). A second mechanism for making organic phosphorus available is carried out via phytases, such as Bacillus and Pseudomonas. Their hydrolysis releases inorganic phosphorus in the form of phosphate groups.

Iron case

Iron is one of the essential trace elements for plants. It is abundantly present in soils in its ferric form (Fe3+). This form is poorly soluble and difficult for plants to acquire. Its absorption therefore requires a transporter. Some bacteria can release siderophores, low molecular weight molecules with a strong affinity for iron capable of forming complexes with Fe3+ to extract, chelate, and transport iron near the roots. This complex is recognized at the root level by specific protein receptors, where it can then be absorbed by plants. Plants themselves produce phytosiderophores, so PGPR help reinforce this mechanism.

Nitrogen case

Diazotrophic bacteria are capable of converting atmospheric dinitrogen (N2) into ammonia (NH3). Although the most common are bacteria in symbiosis with legumes, the rhizobia, there are also non-symbiotic diazotrophic bacteria of the genus Azospirillum, Azotobacter, Pseudomonas, or Klebsiella.

Growth stimulation by phytohormone production

Phytohormones are molecules naturally produced by plants, which can stimulate or inhibit plant growth. The phytohormones involved in growth stimulation belong to three main families:

- Auxins,

- Cytokinins,

- Gibberellins.

Some PGPR are capable of producing these hormones.

Auxins

Plant-derived auxins are known to inhibit terminal bud growth but are also involved in cell growth and differentiation. They participate in cell elongation and proliferation, rhizogenesis and other organogenesis, as well as transcription. When synthesized by bacteria, auxin has three main functions:

- Stimulating the increase of root surface area and length, giving the plant access to a large soil exploration volume for better nutrient acquisition.

- Loosening cell walls at the root hairs to facilitate exudations, an energy source for bacterial development.

- Increasing germination speed.

Gibberellins

Gibberellins are involved in several plant growth processes, notably cell elongation at meristems, inducing stem elongation and root growth, breaking dormancy, and floral induction.

Some bacteria can produce gibberellins as secondary metabolites, involved in signaling pathways of plant-bacteria interactions. In this case, gibberellin stimulates aerial and root growth and maintains plant structure.

Cytokinins

Cytokinins, combined with auxin, serve for tissue proliferation via stimulation of cell division, organogenesis, and differentiation of certain organs. Finally, these molecules are involved in slowing leaf senescence.

Phytohormones thus have a direct role in plant growth but can also intervene in other metabolic and signaling pathways.

Increase in tolerance to abiotic stresses

Stress conditions trigger signaling pathways and physiological responses in plants. These are modulated by specific molecules.

Ethylene is a phytohormone that plays a signaling role in many physiological processes. It is notably involved in response to abiotic stresses. When ethylene is produced in large amounts, it inhibits plant growth and induces senescence, chlorosis, leaf drop, or even plant death. ACC – 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid – is the direct precursor of ethylene. It can be cleaved by ACC deaminase, an enzyme secreted by bacteria such as Pseudomonas putida or Azospirillum brasilense. These PGPR use the degradation products of ACC – ammonia and ketobutyrate – as energy sources and are thus able to modulate ethylene production. Consequently, plant growth is maintained under stress conditions.

Inhibit bioaggressors by competition

The primary purpose of PGPR used as biostimulants is not competition against bioaggressors. However, this can have an indirect effect on plant protection and growth.

Around the roots, microorganisms compete for access to nutrients. Siderophores released by PGPR trap iron in complexes that soil pathogens cannot use. It also appears that siderophores produced by PGPR have a higher affinity for iron than chelators released by other organisms, giving them a competitive advantage. The role of siderophores is thus twofold: on one hand, they serve the nutrition of PGPR bacteria and the plant; on the other hand, they reduce reserves for pathogenic microorganisms.

La technique est complémentaire des techniques suivantes

Sources

- ↑ Académie des biostimulants, online, MICROBIAL BIOSTIMULANTS: The example of bacterial microorganisms/