The Successive and Symbiotic Development of Plants and Soil Life

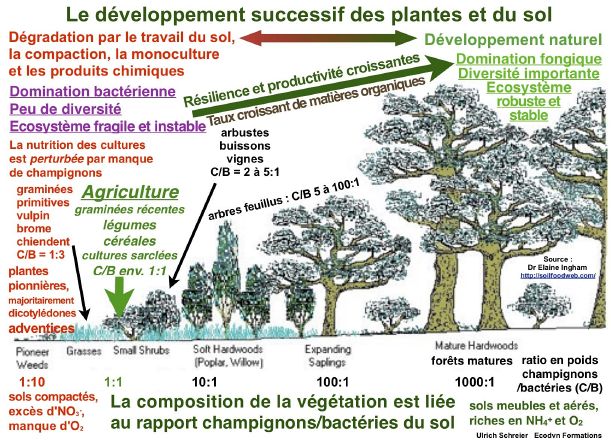

Dr. Elaine Ingham, world-renowned American biologist, also known for her work on the soil food web (Soil Food Web), oxygenated compost tea and foliar fertilization, has studied thousands of soil samples across the globe. This study notably revealed a relationship between the chemical, physical, and microbiological properties of the soil and the type of plants growing there, each plant living in symbiosis with its characteristic microbial "herd". A particularly interesting phenomenon concerns the correlation between the type of vegetation growing in a place on one hand and the fungi/bacteria ratio (F/B) and carbon/nitrogen (C/N) ratio on the other.

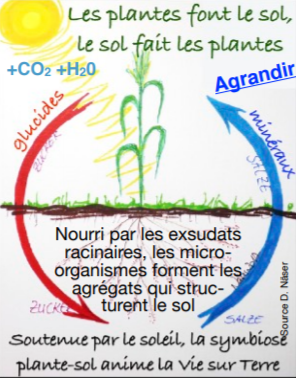

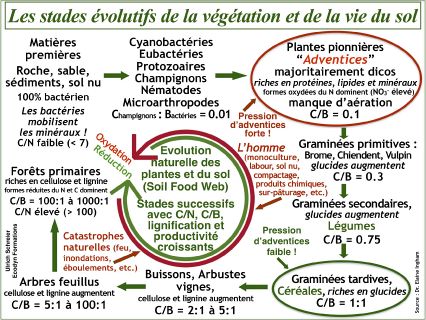

Since the dawn of time, the plant world began with some primitive plants such as lichens and mosses which, thanks to photosynthesis with its reducing power (in the sense of redox potential), generated by the energy and electron flow from the sun, developed on a mineral substrate (parent rock) in symbiosis with a multitude of bacteria capable of attacking and solubilizing it.

Over the years, this primitive vegetation in symbiosis with the microbial world produced organic matter to evolve towards increasingly complex forms and microbiota as well as soils increasingly rich in carbon substances, bacteria, and fungi (increasingly high F/B and C/N ratios), the ratio between fungal biomass and bacterial biomass reaching up to 1000 to 1 in some primary forests.

During this evolution towards increasingly diverse and complex ecosystems, more and more stable, resilient, and productive, "pioneer" plants appeared, mostly dicotyledons at first, then followed by primitive grasses (blackgrass, sterile brome, couch grass, etc.). These are in a way the brothers and sisters of our weeds.

The role of dicotyledons, generally rich in proteins, lipids, minerals, and bacteria, is to prepare (…or repair) the ground for our crop plants which for most of them grow best in soil rich in humus, bacteria, and fungi with a fungi/bacteria ratio around 0.5 to 1.5. Any significant deviation towards bacterial dominance and an oxidizing environment rich in nitrate (NO3-), the oxidized and low-energy form of N requiring more energy for plant assimilation), as caused by much of practices in agriculture, destabilizes the plant-soil ecosystem.

Often accompanied by mineral, enzymatic, and hormonal imbalances, the result is seen in compacted soils with disturbed rhizospheric flora and weakened crops, leading to proliferation of weeds, diseases, and bio-aggressors. This degradation also affects the consistency, quality, and flavor of produce and, consequently, the health of animals and humans who depend on it for their food.

Bacteria have an affinity for dicotyledons, notably legumes and crucifers, which, rich in proteins, lipids, and minerals, decompose rapidly (nitrophilous pioneer plants - weeds - low C/N and F/B).

Fungi need bacteria and plants with mycorrhiza rich in carbohydrates, particularly grasses (high C/N). Due to functional complementarity, grasses (Poaceae) are often grown in association with legumes (Fabaceae) and crucifers (Brassicaceae).

- This article comes from the document Wouldn't our agriculture be making life easy for weeds and pests? written by Ulrich Schreier in 2021.

La version initiale de cet article a été rédigée par Elaine Ingham et Ulrisch Schreier.