Successfully Transitioning to Pasture Grazing

Putting out to pasture is the start of the grazing season. It is a step for the farmer, the animal, and the land. It is a crucial moment of the forage year mixing excitement "we want to see the animals outside" and fear "we must not cause diarrhea nor penalize grass growth".

Putting out to pasture represents a significant transition for animal performance, productivity, and vegetation seasonality.

Focusing on putting out to pasture allows to:

- Reassure by planning it in advance: putting out to pasture requires farmer choices: deciding the dates to move different groups out of the barn, the areas concerned, the size of paddocks, grazing durations, and the supplementation provided.

- Anticipate consequences on vegetation: putting out to pasture influences plant growth and reproduction cycles. It conditions the quantity and quality of resources available during the year for grazing, as well as forage stocks.

- Soften the dietary transition: putting out to pasture is a change in diet for the animals. A sudden putting out to pasture risks diarrhea or performance drop.

- Build the desired resource: putting out to pasture varies according to seasonality (early/late) and the quality (fiber/green) of the resource sought in grazing.

A strategic period for the farm

Putting out to pasture is the transition between winter practices (barn or deferred grazing) and spring practices (grazing or harvesting). At this time, there are many stakes: take advantage of spring potential, favor summer growth, maintain meadows quality long-term, move animals out, limit parasite risk... and decisions have implications on animals, vegetation, and the system.

A period reducing the need for harvested forage

- Unload the livestock barn at winter's end.

- Save stored forage and nitrogen fertilizer.

A period requiring specific areas

- Choose plots that will not be grazed during the first half of spring.

- Prefer areas where parasite pressure is low to accustom animals to grass.

- Favor bearing surfaces to avoid damaging the forage resource.

A period requiring animal management adjustment

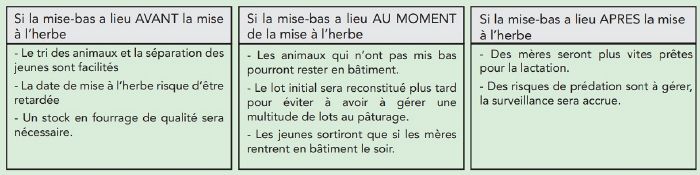

- Key reproductive events (calving, mating, insemination) are difficult to manage during putting out to pasture.

- Grouping is a success factor for putting out to pasture to consider animal needs and area management. Example: it is possible to move out animals with low needs earlier and those with high needs later.

A dietary transition for animals

During putting out to pasture, a challenge from the animals' perspective is to favor a gentle dietary transition to allow time to adapt the rumen flora to the change.

- Use this period to train animals to fencing, build their social behavior and feeding habits.

- Transition refers to any major dietary change, whether for spring or autumn grass, chestnut, acorn, etc. Transition lasts one to three weeks. This is the time needed for rumen microorganisms to adapt to grass.

- When putting out to pasture is started then stopped with a return to the barn, there are minor immediate effects but animal performance is not affected long-term.

Facilitate dietary transition

- Transition duration is considered based on the amount of grass available at putting out to pasture. The earlier it is, the more limited and rich the grass quantity, the longer the transition.

- Grazing on areas not yet used for young animals to limit parasite shocks and help build their immunity.

- Balance between dry and green is ensured either by hay supply or by plots left unfinished in autumn.

- Sheltered or fallback plots are favored to respond to weather hazards. Coarse hay can be used as backup.

- The daily grazing duration is increased progressively.

Vegetation orientation

During putting out to pasture, a challenge from the vegetation perspective is to take advantage of spring grass without compromising the resource for the rest of the year. The putting out to pasture date is a determining factor.

Choose between early or late putting out to pasture

Early turnout

This means going out as soon as vegetation starts.

It is practiced on a large area:

- To depress, restart growth and delay heading

- To clean paddocks and increase spring productivity.

Early turnout theoretically extends the grazing period forward by increasing the number of uses of spring paddocks.

Risks of this practice: there can be "gaps" with fear of bad weather returning. Solutions must be planned. It is safer not to put all groups out at once to reduce risks and facilitate work organization.

Late turnout

This means going out on more advanced vegetation. It is practiced on smaller areas:

- To top some meadows and cut grass heading (improve hay quality).

- To limit risk of hazards early spring.

Risks of this practice: one can be overwhelmed by the spring grass growth explosion, then by heading. This requires accepting refusals and managing them later in the year (late season grazing, mowing or shredding).

Depend less on hay distribution

Prepare plots assigned to putting out to pasture from the previous summer or autumn to find a mixed green/strawy feed at the start of regrowth.

Paddocks are not finished in autumn. Vegetation is productive in spring (because plant reserves are full) and dry grass protection against frost is beneficial.

Manage soil bearing capacity problem

- By reducing animal load on the plot (fewer animals per hectare and/or limited presence duration) or by increasing grazing area.

- By reducing the concerned plot to avoid damaging too many areas.

Then, spring takes place on other plots so that the meadow can withstand grazing with heavy trampling while allowing young seedlings to establish in bare soil zones in spring.

Trampling causes a relative but not irreversible degradation. The spring explosion allows rapid grass recovery.

Autres fiches Pâtur’Ajuste

- Choisir ses pratiques de fauche

- Concevoir la conduite technique d'un pâturage

- Façonner les caractéristiques de la végétation à une saison donnée

- Reconstituer « naturellement » un couvert prairial

- Saisonnaliser sa conduite au pâturage

- Clarifier ses objectifs en pâturage

- Réussir sa mise à l'herbe en pâturage

- L'ingestion au pâturage

- Connaître en renforcer la digestion de la fibre en pâturage

- Les refus au pâturage

- Faire évoluer la végétation par les pratiques en pâturage

- Préférences alimentaires au pâturage

- Bagages génétiques et apprentissages en pâturage

- Le report sur pied des végétations en pâturage

- Préciser ses pratiques de pâturage

- Evaluer le résultat de ses pratiques de pâturage

- Mieux connaître ses végétations en pâturage

- Mieux connaître ses animaux de pâturage

- Les ressources ligneuses en pâturage

Sources:

SCOPELA, with farmers' contribution. Technical sheet from the Pâtur’Ajuste network: Succeeding in putting out to pasture. April 2016. Available at: https://www.paturajuste.fr/parlons-technique/ressource/ressources-generiques/reussir-la-mise-a-lherbe