Seasonal Grazing Management

Seasonal adaptation of grazing management allows to:

- Choose the general strategy of your feeding system: prioritize grazing or stored feed?

- Know how to react to climatic hazards and avoid suffering from excesses or shortages of forage.

- Better rely on the diversity of vegetation on the farm.

- Create forage availability for grazing in spring and at other times of the year.

- Meet the nutritional needs of animals at pasture throughout the year.

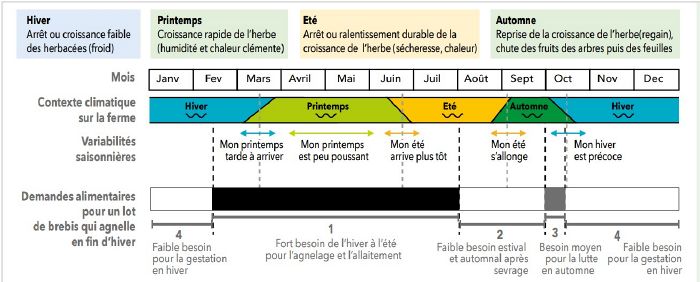

While the change of season is both normal and accepted by all, its unpredictable nature often makes it a challenge for farmers. Although climate change, with its accompanying extremes, gives us a reason to address this topic, it must be acknowledged that farmers have always had to cope with strong seasonal variability.

Identifying the seasons and their variability means:

- Recognizing that vegetation and animal needs evolve throughout the year: this leads to reasoning about the match between animal demand and forage availability at pasture each season.

- Accepting that spring is not the only season in the grazing calendar: this requires reconsidering the nutritional value of vegetation in growth or deferred regrowth regardless of the season.

- Anticipating the effect of animal grazing on vegetation depending on the season: this allows building the ration and controlling plant dynamics.

Analysis of the farm's seasonal context

Each farm has its seasonal particularities. Because, while local climate exists, the parceling has its own seasonal characteristics (i.e., growth periods, heading speeds, ability to remain standing, etc.). Moreover, each farmer defines "their seasons" to manage on the farm for each group of animals according to the nutritional needs they seek to cover and the desired grazing periods.

Climatic seasonal variations

Climatic seasons influence grass growth conditions. They fluctuate according to geographic context and from year to year by temperature and humidity intensity, their onset period, and duration.

Nutritional needs by animal type

Concerns about available vegetation at pasture are primarily dictated by the different periods of nutritional demand of each animal type. This demand varies according to the number of animals and the physiological needs the farmer seeks to cover linked to the reproduction and production calendar. It also depends on the animals' feeding capacity and motivation to graze.

Identifying the diversity of groups and their needs allows distinguishing distinct periods of nutritional demand during the seasons.

Typology of grazed parcels

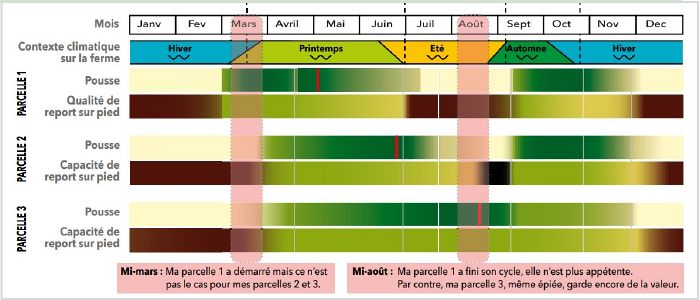

Depending on plant species and site conditions (soil, exposure), the plant cycle occurs at varied rhythms. Plants grow, develop, flower, fruit, and die not synchronously. Thus, within a farm, in the same season, some parcels are in full growth while others have not started.

Identifying plant functioning allows to identify types of vegetation or parcels, which offer different forage availability for grazing throughout the seasons.

The diversity of vegetation types is an asset to extend grazing.

Each vegetation cover has its own seasonality, offering an easier opportunity for use in a given season. However, the seasonal nature of an area cannot always automatically determine "the right practice" to implement. It is entirely possible to want to use it in another season or to want to evolve the existing vegetation to improve the characteristics actually sought, by adjusting practices accordingly.

Optimization of seasonal pastoral resources

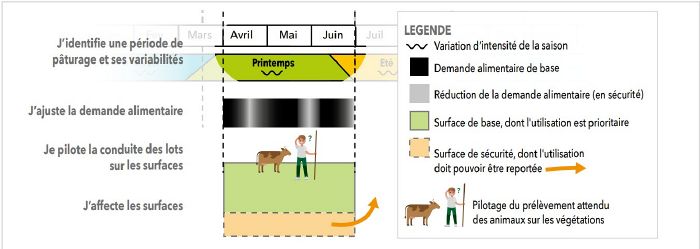

Recognizing the seasons and their variability on the farm leads to accepting that forage availability will not always be as planned and expected. Farmers therefore face, at the beginning, end, or middle of a grazing season, either "not enough forage available" or "too much forage available" relative to the nutritional needs to be met.

Technical levers exist to successfully match the feed demand of groups at pasture with the available vegetation on the surfaces during seasonal uses.

Adaptation of feed demand

Farmers make strategic choices by organizing feed demand by season for each group. They can activate different levers to vary this demand:

- Reorganize allotment: for example by adjusting the size of the group (increasing or decreasing the number of animals) or by splitting an existing group into two if animals have different needs (creating a group with lower needs to be managed on less rich areas and a group with higher needs on greener areas), etc.

- Adjust levels of needs and coverage: for example by earlier weaning, accepting a decrease in milk quantity or growth/fattening rate (recoverable if possible during a more favorable period), shifting the peak of milk production or calving dates, etc.

- Modify marketing choices: for example by advancing sale periods to reduce a group of animals, changing the type of cheese produced to adapt to the available milk quantity, etc.

Strategic allocation of pastures

This involves deciding the types and quantity of areas dedicated to a group of animals with defined nutritional needs for a given season, taking into account the usual intensity or duration of the season and results from past years' experience.

Which types of area to choose?

It is logical to rely on the seasonal aptitudes of vegetation to decide which parcels to prioritize for a given season. For example, meadows growing in spring and autumn, cool environments more or less deferred regrowth for summer, dry environments with deferred regrowth for winter, etc. But it is entirely possible to want to use them in another season or to want to evolve the existing vegetation to improve the characteristics actually sought, by adjusting practices accordingly. For example, grazing or mowing regrowth, more or less complete grazing deferrals, etc.

How much area to allocate to a given season?

The farmer plans, if possible, base and safety areas. Base areas are primarily allocated for the given season. They can be deliberately reduced to facilitate management of the expected grazing pressure on vegetation.

Safety areas must be optionally usable in a given season. That is, vegetation management can be deferred (they can serve as base areas for another season).

Seasonal grazing management

Animal management on chosen areas ensures the success of matching targeted feed demand and available vegetation during a given grazing period. Choices of parcel exploitation mode allow directing the successive grazing by animals on vegetation. This grazing is decided both:

- To act on the ration taken according to needs to be met. Livestock and grazing practices influence the nature and speed of animal intake (motivation, ingestion stimulation, food learning, etc.) and thus modify the ration value on the same vegetation. For example: animals can be allowed to select at pasture; vary instantaneous stocking rate; organize feeding during the day (day and night paddocks, herding circuit, attraction points, etc.); provide complementary and motivating forage relative to the forage to be grazed; or teach and accustom animals to broaden their bite range and ingestion or digestion capacity to valorize deferred regrowth vegetation.

- To act on what is left. Practices influence the annual development cycle of plants which modifies the nature of the available forage (especially the proportion of green and stemmy material at a given time) and environmental conditions. This affects vegetation available for the next use. For example: pruning in spring delays senescence and thus extends the availability period of "green"; topping, by preventing seed setting, restarts vegetative growth and improves deferred regrowth quality for summer.

- To act on the maintenance or evolution of vegetation over the years according to objectives. Practices influence plant living conditions: vegetative or seed reproduction, seedling survival, survival linked to plant reserves, competition between species linked to environmental conditions (fertility evolution, light, etc.). Thus, they favor or penalize certain plant species. For example: repeated grazing on growing grass or woody plants penalizes plants depending on their reserve accumulation speed (dwarfing or mortality of herbaceous or woody species); maintaining tall grass or woody plants enhances freshness and fertility conditions (soil protection); etc.

Program management for each animal group and season

Pasture feed resources are produced by seasonal management of animals and areas. They do not depend solely on climatic or site conditions.

Programming the management of animal groups and areas at a given time helps, with experience from previous years, to adapt to seasons and their variability by planning, at a given time, a "base" management and a "safety" management to succeed despite seasonal variability.

Autres fiches Pâtur’Ajuste

- Choisir ses pratiques de fauche

- Concevoir la conduite technique d'un pâturage

- Façonner les caractéristiques de la végétation à une saison donnée

- Reconstituer « naturellement » un couvert prairial

- Saisonnaliser sa conduite au pâturage

- Clarifier ses objectifs en pâturage

- Réussir sa mise à l'herbe en pâturage

- L'ingestion au pâturage

- Connaître en renforcer la digestion de la fibre en pâturage

- Les refus au pâturage

- Faire évoluer la végétation par les pratiques en pâturage

- Préférences alimentaires au pâturage

- Bagages génétiques et apprentissages en pâturage

- Le report sur pied des végétations en pâturage

- Préciser ses pratiques de pâturage

- Evaluer le résultat de ses pratiques de pâturage

- Mieux connaître ses végétations en pâturage

- Mieux connaître ses animaux de pâturage

- Les ressources ligneuses en pâturage

Sources:

- SCOPELA, with the contribution of farmers. Technical sheet from the Pâtur’Ajuste network: Seasonal grazing management. November 2020. Available at: https://www.paturajuste.fr/parlons-technique/ressource/ressources-generiques/saisonnaliser-sa-conduite-au-paturage