Genetic baggage and learning in grazing

Better understanding the genetic backgrounds and learning of animals allows to:

- Better choose the type of animals on the farm: when setting up, farmers must decide on the type of species, breed or group of animals to raise on the farm depending on the targeted productions, the farming methods and the local context.

- Understand certain behaviors and succeed in expressing the animals' potential: the farmer holds the keys to shape animals according to his farming system. However, one must be aware of this and improve technical skills to succeed.

- Not hide behind preconceived ideas : breed is often blamed for the animal's ability to produce under certain farming conditions, yet things do not always go as expected...

- Not miss the education of the animals : young age is crucial to accustom animals to their future living conditions and prepare them to produce in the farm environment.

The breed of farm animals is often highlighted to distinguish production aptitudes, behaviors or adaptations to the terroir. Yet contradictions among farmers about the supposed traits of this or that breed show the difficulties we all have in truly distinguishing what is innate (genetic background) or acquired (learning depending on living conditions and farming practices).

The skills of farm animals

The skills of an adult animal do not come only from its genetic background

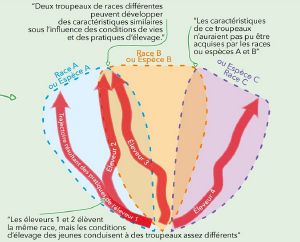

It seems impossible to separate aptitudes, which would be determined by genetics, and skills, which would be acquired during the animal's life. Both factors coexist and form the herd characteristics (feeding skills, digestive physiology, production level, etc.). Some seem more linked to the animals' genetic background, others seem more dependent on practices.

Genetics and practices: a potential to express

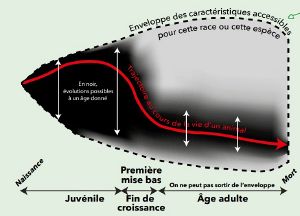

The diagram opposite illustrates, for a given animal, breed or species: its finite genetic potential ("envelope of accessible characteristics for this breed or species") as well as the trajectory taken during its life depending on the farmer's practices and objectives.

Nevertheless, you cannot do everything with a breed. Limits exist. Indeed, it is difficult through practices to straighten an animal lacking genetics and conversely difficult to slow down an animal with too much. This is the case for milk production: "a cow with genetics to produce around 10,000 liters per lactation can produce 7,000 liters without difficulty but not 4,000."

The diagram opposite explains that there can be a diversity of skills among animals of the same breed depending on farms and conversely similar skills between animals of two herds of different breeds.

Learning abilities decrease with age

Many farmers report that learning abilities are higher in the young and decrease with age. Animal sciences explain this by the fact that the young have more attraction than fear for novelty. This difficulty to evolve in adulthood is even more striking for traits linked to anatomical development. For example, the size of the rumen (future ingestion capacity of the animal during its career), or the walking ability (future capacity of the animal to move) are generally acquired before the end of growth: "there are key moments in the animal's life, if you

succeed at them, it's won for life!"

For example, if a herd of goats is moved out of a paddock as soon as it shows the first signs of boredom, their expectation for changing paddock is reinforced. It is concluded that "goats" can never finish a paddock. Yet, it is the tacit agreement between the farmer and his animals that gradually builds the herd's ability to finish a paddock before moving to another.

The trajectory of an animal during its life is built by the farmer

By regularly observing the attitude and/or physiology of animals, it is possible to decide adjustments in management to not endure but choose their future behaviors. These adjustments cannot always be in a logic of producing "more and faster". Slowdowns in growth or milk production allow building for the future skills to produce "well" (quality of milk or meat) or "cheaper" (limiting purchases, reducing mechanization).

And selection in all this?

It determines the range of accessible skills for a breed. Changing selection criteria allows evolving the range of animal characteristics. Scientists have shown variable heritabilities depending on criteria (example: growth highly heritable, disease resistance poorly heritable) and correlations or antagonisms between some of them (example: milk quantity inversely correlated with protein content; protein content correlated with butterfat content).

Diversity in the herd: asset/constraint?

Depending on the system and production objectives, a range of characteristics are considered "acceptable". Unacceptable characteristics are then used for culling. Depending on farmers' priorities (production, docility, fertility, age...), their number and nature vary. Despite similar genetic background and practices, there is diversity among individuals of the same herd. Some farmers consider this diversity not a handicap but an asset and decide on a very wide range of characteristics. This can go as far as forming multi-breed or multi-species herds to play on their complementarity. Others adopt stricter culling strategies, seeking very homogeneous characteristics within the herd.

Enrichment of some preconceived ideas

The skills of individuals of two different species can be more similar than between individuals of the same breed.

Attributing the consumption of woody vegetation exclusively to goats is a reflex supposedly explained because they have a more adapted diet. Yet, in territories, it is not uncommon to find goats whose ration is exclusively grass and cows grazing on scrub. Through his practices, the farmer manages to reduce the gap between the innate aptitudes of species. Only a few traits seem very determined by species genetics and thus cannot be changed by farmers: animal size and food prehension.

An animal becomes hardy if farming conditions allow it

Buying rams of a hardy breed from selection organizations to improve the offspring's aptitudes is often practiced in farms. However, it is clear that once on the farm, the ram will look up in the air for several days and stop growing before understanding that what is on the ground is edible. Farm animal behaviors are dictated by their early experiences, feeding habits, social relationships in the herd and also memory of places and activity rhythms. Thus, a hardy breed animal, due to its farming mode before arriving on farms, can be quite incompetent to valorize the environment it discovers. It will take about two years to build consumption, digestion habits, etc. to become able to live in its environment.

How to choose a species and a breed?

A species, a breed is chosen:

- first based on their appeal (empathy, aesthetics, territory of origin, etc.): "We choose a breed because we like this breed. Then, there is also the local ease, the surfaces and the forage available, the desired marketing..."

- and secondly based on the farming method desired by the farmer: "When you like a breed, you have to try to adapt it to your system. If it doesn't work, you have to switch to another."

Autres fiches Pâtur’Ajuste

- Choisir ses pratiques de fauche

- Concevoir la conduite technique d'un pâturage

- Façonner les caractéristiques de la végétation à une saison donnée

- Reconstituer « naturellement » un couvert prairial

- Saisonnaliser sa conduite au pâturage

- Clarifier ses objectifs en pâturage

- Réussir sa mise à l'herbe en pâturage

- L'ingestion au pâturage

- Connaître en renforcer la digestion de la fibre en pâturage

- Les refus au pâturage

- Faire évoluer la végétation par les pratiques en pâturage

- Préférences alimentaires au pâturage

- Bagages génétiques et apprentissages en pâturage

- Le report sur pied des végétations en pâturage

- Préciser ses pratiques de pâturage

- Evaluer le résultat de ses pratiques de pâturage

- Mieux connaître ses végétations en pâturage

- Mieux connaître ses animaux de pâturage

- Les ressources ligneuses en pâturage

Sources

SCOPELA, with the contribution of farmers. Technical sheet of the Pâtur’Ajuste network: Genetic backgrounds and learning. July 2017. Available at: https://www.paturajuste.fr/parlons-technique/ressource/ressources-generiques/bagages-genetiques-et-apprentissages