Effect of Wheat Sowing Date on Weed Infestation

The choice of the sowing date is an essential factor to consider for the success of the crop. Delaying the sowing of winter cereals by a few days compared to the usual periods can allow for better management of weed flora afterwards, especially grasses.

Principle

The shift in sowing date allows:

- To avoid the preferred germination period of grasses if agro-climatic conditions are met (refined soil, rewetting of soils).

- To intervene after the dormancy break of blackgrass seeds and make them germinate before the sowing of wheat.

- To position autumn chemical interventions under better conditions (soil generally wetter in November).

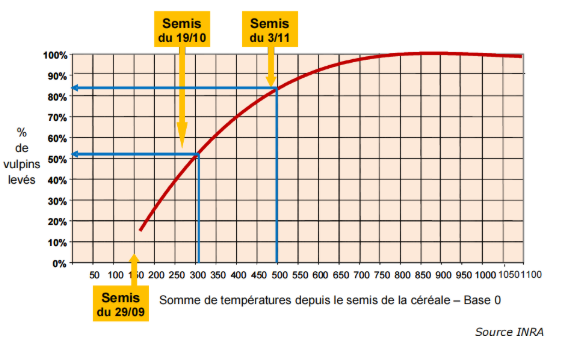

Blackgrass germinates about 150 DD (degree days) after superficial soil work. A sowing on September 25 is almost simultaneous with blackgrass germination. 100% of the population thus emerges at the same time as the crop. However, a shift to October 19 allows avoiding 50% of potential blackgrass and 80% for a sowing on 11/3.

Results of the practice

The question now arises about feasibility and impact on yield.

And the regulation of other weeds?

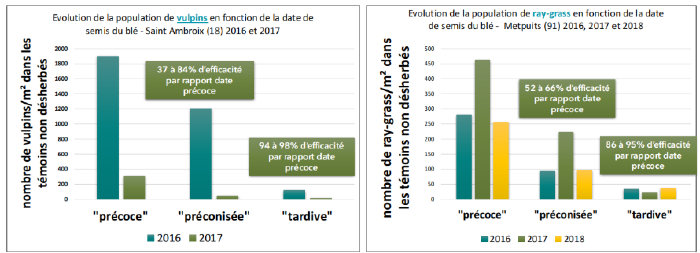

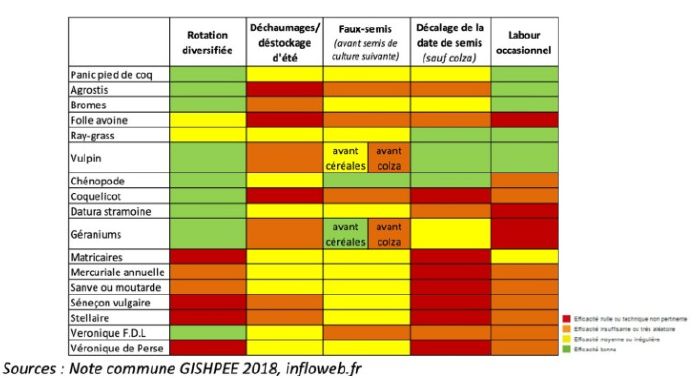

The practice of shifting sowing dates is really effective only against monocotyledons and differences in sensitivity are also observed within this category. Only the regulation of blackgrass and ryegrass is significant. Conversely, for the vast majority of dicotyledons (except goosefoots), the effect of the practice is not demonstrated or simply null.

Impact on yield

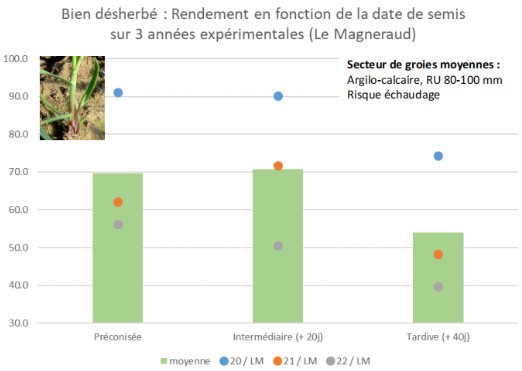

Delaying soft wheat sowing by 20 days compared to the optimal period has little impact on yield (on average, over 3 very contrasting climatic campaigns).

However, as seen, at +20 days, blackgrass density is reduced by 40%.

At +40 days, when pressure is reduced by 75%, yield loss is around 15 quintals.

Feasibility

In general, from November onwards, the later the interventions, the greater the risk of being limited given the number of days when work is possible.

Feasibility level is highly dependent on local context and climatology.

Sowing at the end of October offers as many available days for intervention (days when the necessary good conditions for sowing are met) as mid-October.

However, late sowings (mid-November and later) reduce the number of days when fields can be accessed. If the number of hectares to be sown is large, it is advisable to prioritize the weediest fields for late sowing.

The same issue arises for late sowings regarding weed control interventions. The number of days available for post-emergence treatments may be limited; it is recommended to anticipate and plan for pre-emergence weed control.

Conclusion

The shift remains a powerful lever to reduce the number of problematic weeds in winter cereals (notably with the emergence of resistance in blackgrass). To guarantee its benefit, it must be combined with optimal timing of chemical weed control from autumn (pre-emergence or early post-emergence). In heavily infested situations, at the system scale, it must be reinforced by other levers (rotation, soil work, false sowing…).

Delaying sowing by 20 days allows reducing the pressure of certain weeds (-40% blackgrass density on average) and thus their harmfulness while maintaining yield potential.

Source

This article was written by Jasmin Razongles, agronomy engineering student in apprenticeship at the Centre National d'Agroécologie.