Climate impact of organic soil management

Agriculture plays a major role in climate change. As one of the main producers of greenhouse gases, agriculture contributes to global warming but also has great potential for mitigating climate change. At the same time, agricultural production and the environment is burdened by the adverse consequences of climate change. Organic farming is one way of adapting agriculture to climate change. Organically farmed soils emit less climate- damaging nitrous oxide than their conventional counterparts. A more active and diverse microbial community present in organic soils can also improve the capacity of crops to adapt to climate-related stress situations. Reduced tillage is a soil organic matter management technique that can help organic farms maintain and increase the amount of organic carbon stored in the top soil.

Agriculture – a key player in climate change

Increase in atmospheric carbon concentration

Carbon dioxide (CO₂), among other greenhouse gases (GHG), is responsible for the average global annual temperature on earth to remain at +15 °C and consequently for life on earth as we know it. The more GHG there are, the warmer the earth‘s surface and atmosphere become. Over the last 250 years, human emissions of GHG have led to an increase in the atmospheric concentration of CO₂ from 280 ppm to currently 405 ppm. This increase is accompanied by an increase in the average global annual temperature by 1 °C (until 2017). In Switzerland e.g., we have recorded a temperature rise of 2 °C in the same period!

High emissions from agriculture

Agriculture directly causes 11.2 % of the global GHG emissions[1]. However, if indirect emissions are included, like the provision of agricultural inputs such as chemical fertilisers and pesticides, and emissions from deforestation for the production of animal feed, the sector contributes between 21–37 % of global GHG emissions[2]. In Switzerland, agriculture accounted for 12.8 % of total GHG emissions in 2018[3]. Figure 2 shows the distribution of emissions from Swiss agriculture in 2015[4]. While only the green parts of the figure represent emissions officially assigned to the agriculture sector, the figure also shows indirect agricultural emissions caused by land-use changes, fuels and combustibles, as well as emissions from the production of fertilisers, etc.

Greenhouse gases

The major GHGs in the earth‘s atmosphere are water vapour, carbon dioxide (CO2), ozone (O3), methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O). CO2, CH4 and N2O are the GHGs most strongly affected by human activities. In contrast, water vapour and ozone concentrations are stable in the long term or only indirectly influenced by humans. Of global GHG emissions from agriculture, 46 % is N2O, 45 % CH4 and 9 % CO2. Fluorocarbons are the only GHGs that are produced solely by human activity. They occur in the atmosphere only in low concentrations, but due to their extremely high warming potential (up to 14,800 times higher than CO2), they have a significant impact on the climate. CO2 coming from the biological processes of decomposition and respiration is largely balanced by photosynthesis. Land-use change from forest or grassland to arable land, burning fossil fuels and liming are major sources of CO2 resulting from human activity. CH4 mainly comes from anaerobic decomposition processes in soils (paddy rice cultivation and wetlands) and anaerobic digestive processes of ruminants, and N2O is produced especially during and shortly after the application of nitrogen fertilisers under anoxic conditions, whether from organic or industrial origin.

CO2 equivalents

The GHGs, CO2, CH4 and N2O, have different global warming potentials (GWP). To compare their GWP, and because CO2 across all sectors is by far the most important GHG, GWP for CO2 is set equal to 1. In comparison, methane (CH4) has a GWP of 24 and N2O 298. The definition of GWP includes the lifetimes of GHG in the atmosphere.

Gigatonne (Gt)

Gigatonne is a widely used unit for GHG quantities. One gigatonne is 1,000,000,000 tonnes (1 billion) and corresponds to 1×1015 or one trillion grams. Another term for the same magnitude is one petagram (Pg). We use humus and soil organic matter synonomously, based on the measured organic carbon multiplied by 1.72.

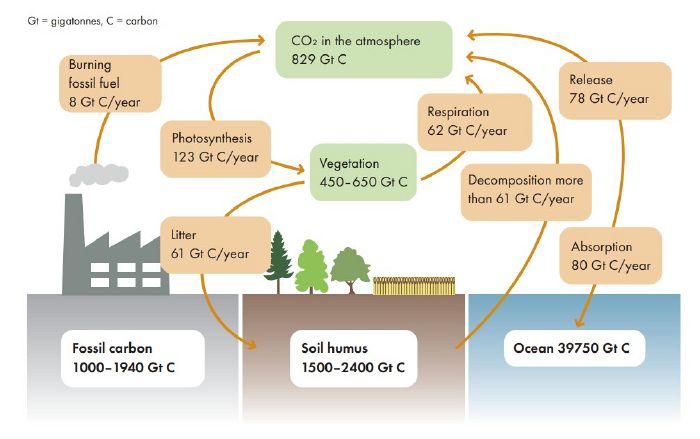

Soil – an important CO2 sink

34 Gigatonnes of CO₂ equivalents were emitted worldwide in 2018, mainly through the combustion of fossil fuels. In the context of the global carbon cycle, these annual emissions are actually quite low (Figure 1). In total, there are 75 million Gt of carbon on earth, 99.94 % of which is bound in limestone. 0.05 % is bound in the oceans and only 0.0037 % in soils. Soils contain twice as much carbon as atmosphere and the terrestrial biomass together, each representing 0.001 % (Figure 1). To compare emissions from the various sources and greenhouse gasses CO₂ is used as the unified currency and is often expressed as CO₂ equivalent (CO₂eq.).

Humans can only influence the carbon content of the atmosphere, soil and vegetation. In this context, agriculture plays an essential role in mitigating climate change. Through building soil organic matter, more CO₂ is sequestered from the atmosphere. Small changes in the soil carbon pool can have significant impacts on the climate.

Beyond this, however, agriculture offers further strategies to mitigate anthropogenic climate change, while enabling agricultural production to adapt to the changing climate conditions that have already been set in motion.

Organic farming – a climatefriendly alternative

Long-term experiments, such as the DOK experiment in Therwil, Switzerland, the tillage experiment in Frick, Switzerland, literature studies (meta analyses), results from the EU Horizon 2020 project iSQAPER, and farm comparisons by Agroscope, allow the following conclusions regarding the climate impact of organic farming to be deduced:

- Organic farms with grass-clover in the rotation and the use of manure and slurry as fertilisers offer good conditions for maintaining or increasing soil organic matter.

- Reduced tillage in organic farming can accumulate soil organic matter in the top soils.

- Thanks to lower nitrogen inputs and improved soil fertility, nitrous oxide emissions in organic farming are 40 % lower than in conventional farming.

- Thanks to more diverse and active microbial communities in the soil, organically cultivated soils mineralise from organic sources more efficiently to plant available nitrogen during drought stress. They are thus better adapted to threats imposed by climate change.

- Per unit yield, the organic farming systems in the DOK trial used 19 % less energy than the conventional ones. Per unit of land, the energy use was even 30–50 % lower than in conventional systems.

Sequester more carbon with humus

In a comprehensive literature review, it was shown that organically farmed soils annually store 170–450 kg more carbon per hectare compared to conventional[5]. The difference results mainly from the cultivation of clover-grass in arable rotations and organic fertilisation. A higher humus content in the soil increases the water infiltration and storage capacity of the soil, as well as the stability of soil aggregates, which also prevents soil erosion[6]. Furthermore, the active proportion of soil organic matter can improve plant health[7][8]. Analyses of 2.000 soil samples in the 40-year duration of the DOK trial near Basel, Switzerland, the longest comparative trial worldwide between organic and conventional farming systems[9][10], show that the:

- Humus content increases slightly in biodynamic cultivation with the addition of compost.

- Humus content decreases significantly in conventional cultivation with purely mineral fertilisation.

- Humus content in conventional cultivation, with the use of both organic and mineral fertilisation, and organic cultivation remains almost stable.

Yields of all crops, averaged over six crop rotation periods over 42 years in the DOK trial were 20 % lower in the organic systems as compared to conventional. This was achieved with significantly lower fertiliser use and without synthetic chemical pesticides.

Reduced tillage – reduced emissions

Reduced tillage is not only good for soil protection but also has potential for climate protection. By replacing deep ploughing with shallower, mostly non-inversion tillage, the humus content can increase significantly compared to the one of organic farming with ploughing[11]. In FiBL‘s 13-year soil tillage trial in Frick, the humus content in the upper 50 cm increased by 8 %. Over the entire duration of the experiment, the humus content increased annually by around 700 kg carbon per hectare under reduced tillage while greenhouse gas emissions remained constant[12][13]. A study within the framework of the Swiss National Research Programme “NRP 68 Soil Resources” compared soil samples from 60 winter wheat fields of either organic with plough use, conventional with plough or conventional notill farms[14]. The study has shown that organic farming promotes humus formation just as well as no-till conventional farming in the top soil layers. No-till farms do not use the plough at all but control the weeds chemically with Roundup, a glyphosate-containing herbicide. Compared to no-till and conventional farms, soils of the organic farms have a more active and complex biological community[15].

Lower nitrous oxide emissions

A meta study of the scientific literature on N₂O emissions from soils of organic and conventional fields shows organic emits less N₂O per land unit than conventional, however slightly more is emitted per yield unit[16]. According to this meta study, a yield increase of 9 % in organic production would be necessary to reduce the yield-related N₂O emissions to the level of the conventional system. A study conducted by FiBL in the 40-year-old DOK trial[16] shows that area related N₂O emissions in organic and biodynamic systems were on average 40 % lower than in the conventional systems. This is explainable by the lower N fertilisation and better soil quality in the biodynamic system in particular[17].

Organic soils adapt better to climate change

Climate change is likely to lead to more heavy rainfall events and droughts. FiBL research results show that soils farmed organically are better adapted to these challenges than their conventional counterparts.

For example, the organic soils in the DOK trial show better aggregate stability as a result of the higher humus content[18]. Accordingly, these soils are better protected against erosion due to heavy rainfall events.

A literature review revealed that microbial activity in organically managed soils is significantly higher than in conventional soils, including protease activity[19]. Protease is an enzyme that catalyses the mineralisation of organically bound nitrogen. In a pot experiment with soils from the DOK experiment, researchers from FiBL demonstrated that under drought stress conditions, soils from organic farming mineralised 30 % more nitrogen from green manure than soils in conventional agriculture[20]. The improved mineralisation performance of organically cultivated soils could be explained by the increased diversity of microorganisms. A recently published study confirms this finding that extensive cultivation leads to better adaptation to drought stress in arable and grass-land soils thanks to more diverse microbial communities[21]. Further FiBL studies have shown that bacterial and fungal inoculants have been able to significantly increase yields in low-input systems, particularly in the Mediterranean and dry subtropical climate[22][23][24]. This demonstrates the potential of these inoculants for crop performance and the yield related climate balance in low-input systems.

Organic – more energy efficient

The resource use efficiency is a fundamental indicator of a production system’s sustainability. To calculate the energy efficiency, in addition to the direct energy use (e.g. fuel for tractors), the indirect energy required to produce inputs (e.g. fertiliser or pesticides) are also taken into account.

Organic farming methods in the DOK trial require slightly more energy for infrastructure and machinery than conventional farming (e.g. for mechanical hoeing and harrowing), but much less energy for fertilisers and pesticides. On average over 20 years, the organic farming systems needed 19 % less energy to produce a yield unit[25], and related to the land area, it was even 30–50 % less energy.

Conclusions

Making better use of climate mitigation potentials

In conclusion, soil management according to organic principles reduces the negative effects of agriculture for the climate, and organic farming systems are better adapted to climate change. Reduced tillage under organic conditions (without herbicides) is a vital means to make organic farming even more climate-friendly. However, intensive research is needed to make weed control even more efficient[11][26]. There lies great potential in precision farming techniques. The relative advantage of organic farming in terms of climate impact is highly depending on the land‘s productivity, which under conventional condition is manageable by adding reactive nitrogen an pesticides. Here, organic farming has a higher land requirement due to lower yields. For this reason, the further development of organic farming through breeding for adapted varieties, more effective organic plant protection and nutrients by using urban green waste compost and digestates from biogas production as fertilisers, is decisive. The potential of biofertilizers to boost crop yields still has to be exploited, especially in arid ecosystems. FiBL researchers have shown that by expanding organic farming, major ecological benefits are realised because existing farmland is better protected against erosion. Worldwide, 10 million hectares of arable land is permanently lost to wind and water erosion every year. Further expanding the area under organic farming is therefore also important for soil protection[27]. However, effective soil and climate protection requires further measures, such as reducing food waste and meat consumption from porc and poultry in particular since humans compete for the same foodstuff (cereals, maize and soy beans. In doing so, global arable land area would not have to be expanded with an increase in organic farming[28]. Overall, organic farming is already making an important contribution to climate protection and is also better adapted to the climate changes already underway.

Open questions

There is still a need for scientific clarification in several areas.

- In the field of soil organic matter and soil quality, projects are currently underway to stabilise humus content, to provide optimum fertilisation to boost humus production and optimum humus content of a given soil, accounting for plant nutrition.

- In the field of GHG emissions, there is a need for emission measurements over entire crop rotations and during manure storage and application, as well as for methane emissions resulting from livestock farming.

- In the political sphere, research is being conducted regarding the optimal tools for promoting agriculture according to food security, climate protection, biodiversity and resource efficiency. FiBL Research: Application of farmyard manure in the Frick reduced tillage experiment. GHG emissions are measured at events when peak emissions are expected.

Sources

Paul Mäder et. al. (FiBL), 2022, Soil and climate – Climate impact of organic soil management. Available on : https://www.fibl.org/fileadmin/documents/shop/1349-soil-and-climate.pdf

- ↑ Tubiello et al. (2015). The Contribution of Agriculture, Forestry and other Land Use activities to Global Warming, 1990-2012. Global Change Biology 21, 2655-2660.

- ↑ IPCC, (2019). Climate Change and Land Summary for Policymakers.

- ↑ FOEN (2020). Switzerland’s Greenhouse Gas Inventory 1990–2018: National Inventory Report and reporting tables (CRF). Submission of April 2020 under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and under the Kyoto Protocol. Federal Office for the Environment, Bern.

- ↑ AgroCleanTech, (2019). Übersicht der landwirtschaftlichen Treibhausgase inkl. Vorleistungen, Treibund Brennstoffen und Bodenkohlen stoff (LULUC) 2015. https://www.agrocleantech.ch/images/Klimaschutz/Treibhausgasemissionen_Landwirtschaft/ THG_2015_Kreisdiagramm_gross.png.

- ↑ Gattinger et al. (2012). Enhanced top soil carbon stocks under organic farming. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, 109: 18226-18231.

- ↑ Bünemann, et al. (2018). Soil quality – A critical review. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 120, 105-125.

- ↑ Bongiorno et al. (2019a). Sensitivity of labile carbon fractions to tillage and organic matter management and their potential as com-prehensive soil quality indicators across pedoclimatic conditions in Europe. Ecological Indicators 99, 38-50.

- ↑ Bongiorno et al. (2019b). Soil suppressiveness to Pythium ultimum in ten European long-term field experiments and its relation with soil parameters. Soil Biology & Biochemistry 133, 174-187.

- ↑ Mäder et al. (2002). Soil fertility and biodiversity in organic farming. Science 296, 1694-1697.

- ↑ Fliessbach et al. (2007). Soil organic matter and biological soil quality indicators after 21 years of organic and conventional farming. Agriculture Ecosystems & Environment 118, 273-284.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Cooper et al. (2016). Shallow non-inversion tillage in organic farming maintains crop yields and increases soil C stocks: a me-ta-analysis. Agronomy for Sustainable Development, 36: 22.

- ↑ Krauss et al. (2017). Impact of reduced tillage on greenhouse gas emissions and soil carbon stocks in an organic grass-clover ley winter wheat cropping sequence. Agriculture Ecosystems & Environment 239, 324-333

- ↑ Krauss et al. (2020). Enhanced soil quality with reduced tillage and solid manures in organic farming – a synthesis of 15 years. Scienti-fic Reports volume 10, Article

- ↑ Büchi, L., Walder, F., Banerjee, S., Colombi, T., van der Heijden, M.G.A., Keller, T., Charles, R., Six, J., 2022. Pedoclimatic factors and management determine soil organic carbon and aggregation in farmer fields at a regional scale. Geoderma 409, 115632.

- ↑ Banerjee et al. (2019). Agricultural intensification reduces microbial network complexity and the abundance of keystone taxa in roots. The ISME journal, doi.org/10.1038/s41396-019-0383-2

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Skinner et al. (2014). Greenhouse gas fluxes from agricultural soils under organic and non-organic management — A global meta-analy-sis. Science of The Total Environment, 468–469: 553-563.

- ↑ Skinner et al. (2019). The impact of long-term organic farming on soil-derived greenhouse gas emissions. Scientific reports, 9(1), 1702.

- ↑ Siegrist et al. (1998). Does organic agriculture reduce soil erodibility? The results of a long-term field study on loess in Switzerland. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 69, 253-264.

- ↑ Lori et al. (2017). Organic farming enhances soil microbial abundance and activity – A meta-analysis and meta-regression. PloS one 12, e0180442.

- ↑ Lori et al. (2018). Distinct nitrogen provisioning from organic amendments in soil as influenced by farming system and water regime. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 1-14.

- ↑ Lori et al. (2020). Compared to conventional, ecological intensive management promotes beneficial proteolytic soil microbial commu-nities for agro-ecosystem functioning under climate change-induced rain regimes. Scientific Reports volume 10, Article number: 7296

- ↑ Mäder et al. (2011). Inoculation of root microorganisms for sustainable wheat–rice and wheat–black gram rotations in India. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 43(3), pp.609-619.

- ↑ Schütz et al. (2018). Improving crop yield and nutrient use efficiency via biofertilization—A global meta-analysis. Frontiers in plant science, 8, p.2204.

- ↑ Mathimaran et al. (2020). Intercropping transplanted pigeon pea with finger millet: Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and plant growth promoting rhizobacteria boost yield while reducing fertilizer input. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 4, p.88.

- ↑ Nemecek et al. (2011). Life cycle assessment of Swiss farming systems: I. Integrated and organic farming. Agricultural systems, 104(3), 217-232.

- ↑ Armengot et al. (2015). Long-term feasibility of reduced tillage in organic farming. Agronomy for Sustainable Development, 35(1), 339-346.

- ↑ Bai et al. (2018). „Effects of agricultural management practices on soil quality: A review of long-term experiments for Europe and China.“ Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 265: 1-7.

- ↑ Muller et al. (2017). Strategies for feeding the world more sustainably with organic agriculture. Nature communications, 8(1), 1290.