Carbon sequestration is closely related to biological nitrogen fixation!

According to Australian soil biologist and ecologist Dr. Christine Jones, biological carbon fixation through photosynthesis as well as the assimilation of atmospheric nitrogen by soil microorganisms are intimately linked and lie at the very heart of Nature’s functioning and its ability to make life on earth possible. In this symbiosis, already present billions of years ago in its embryonic form in archaea, cyanobacteria (phytoplankton or algae blue-green, nostocs) combine the symbiotic fixation of C and N in a single organism.

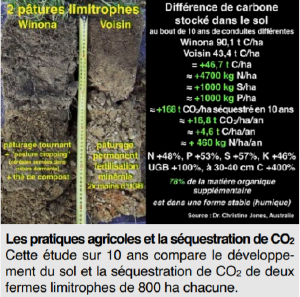

In this pair, the plant provides carbon and energy from photosynthesis in the form of root exudates rich in carbohydrates and electrons (C4- ->C6H12O6), while a multitude of bacteria in the soil fix nitrogen from the air in an electron-rich form (N3- ->NH3 -> NH4+), the transfers in both directions between roots and bacteria being ensured by the filaments of mycorrhizae (see the image on the previous page). This process of cooperation and exchange between plants, mycorrhizae, and bacteria is essential for the fixation of both atmospheric carbon and nitrogen, and lies at the core of the synthesis of stable carbon complexes.

It is therefore indispensable for the formation of humic complexes and stable aggregates. Being perfectly integrated into the soil matrix, these form the habitats of microorganisms while also serving as reservoirs of water and nutrients. However, just like high-dose chemical fertilizers, especially nitrogen products, biocides, and intensive tillage destroy aggregates, mineralize existing organic matter, and disrupt this symbiosis, it is not surprising that humus and nutrient levels in agricultural soils continue to decline and often reach alarming levels.

It would therefore not be the nitrogen fixed by the nodules of legumes, nor that from crops residues or supplied as fertilizer, including organic, that primarily serves the formation of stable carbon complexes, but rather that assimilated by ammoniacal nitrogen-fixing bacteria living inside soil aggregates and symbiotically nourished by root exudates, especially those of grasses (see the diagram on page 7). By a mineralization effect similar to that linked to synthetic nitrogen, nitrogen fixed by legumes grown in the absence of other plants, especially grasses, also tends to degrade organic matter and soil structure (this phenomenon can be seen, for example, under a black locust, a tree of the Fabaceae family native to America). To circumvent this problem, legumes should therefore not be grown alone, but always associated with other plants, particularly grasses which, thanks to root exudates rich in carbohydrates, promote the development of fungi, notably mycorrhizae. Although nitrogen fixed by legumes and that from the decomposition of plant and animal residues contribute only secondarily to the formation of stable humic complexes, they are obviously excellent sources of organic nitrogen to feed crops and for various processes related to good soil functioning.

In addition to disrupting the plant-soil ecosystem, preventing the formation of stable soil aggregates, and being an obstacle to carbon sequestration and the assimilation by crops of minerals and trace elements, nitrogen fertilizers are also a source of ammonia and nitrous oxide (N2O), toxic gases whose greenhouse effect of the latter is about 300 times greater than that of CO2. Due to its mobility and instability, nitrogen losses by volatilization and leaching can be on the order of 50 to 90%, with only 10 to 50% absorbed by plants!!! Nitrogen loss, agronomic, economic, and environmental damages are particularly significant if soluble fertilizers are spread on bare soils in autumn. Losses are even worse for fertilizers based on solubilized phosphates (MAP and DAP) as offered by industry. Without a well-developed soil life, only 10 to 15% would eventually be accessible to plants and at least 80% will form insoluble compounds with cations of calcium, magnesium, aluminum, iron, and certain trace elements, a process that can also lock out other nutrients and cause deficiencies in crops.

In short, for both nitrogen and certain trace elements and phosphorus, this Achilles’ heel of modern agriculture, waste and agronomic damages are considerable. However, with practices more in harmony with natural processes, there is an unlimited source of nitrogen in the atmosphere (78,000 t of N above each hectare!!!) and reserves of phosphorus for several centuries which, today blocked in soils under insoluble mineral forms, can only be mobilized by efficient microbial communities (C. E. JONES - 2014).

La technique est complémentaire des techniques suivantes

La version initiale de cet article a été rédigée par Ulrich Schreier.