Carbon Credits in Field Crops

Carbon credits (or certificates) are tons of CO2 equivalent saved thanks to changes in practices. One ton "CO2 equivalent" is a quantity of greenhouse gases (CO2, CH4, N2O) whose climate effect is equivalent to the effect of one ton of CO2.

1 ton CO2 equivalent saved = 1 carbon credit (CC)

Principle

The number of carbon credits generated by a farm is calculated by making the difference between two scenarios :

- One scenario, called the reference, which corresponds to the current carbon footprint of the farm over past years (from 1 to 5 years depending on providers).

- One scenario, called the project, during which the farmer implements actions that should reduce the carbon footprint.

Carbon credits or certificates are sold on the voluntary carbon market to committed organizations wishing to contribute to the financing of carbon sinks in France. The proceeds from this sale should allow the farmer to partially finance the changes they decide to make on their farm.

What is the objective of carbon credits?

The main objective of the carbon credit mechanism is to promote the transition to less carbon-emitting agriculture and to restore the levels of organic matter (in other words, soil carbon) present in agricultural soils by providing farmers with a funding solution for their project.

For example, the implementation of cover crops during intercrop periods is one of the major levers to increase the return of organic matter and thus improve carbon storage in soils. Recent studies have shown that the expansion of intermediate crops (sowing + destruction) has an average total annual cost of €39/ha/year[1]. This additional cost, amortized over several crop years thanks to soil regeneration but which may reduce the margin per hectare in the first years of implementation, is intended to be supported by the sale of carbon credits.

How are carbon credits calculated?

Carbon credits are calculated by making the difference between the carbon footprint of the reference scenario and that of the project (i.e., the crop year including one or more changes in practices) :

Number of carbon credits = Reference carbon footprint - Project carbon footprint

Depending on the applied methodology, the reference carbon footprint can be calculated based on a single reference year or an average of the carbon footprints of several consecutive years (often 3 to 5 years) before the project implementation. One year is a crop year, for example from November 1st to October 31st.

Similarly, the project carbon footprint can be calculated based on a single year of practice changes or an average of the carbon footprints of a multi-year project (often 5 years in France).

Thus, for example, for a transition project started in 2022 :

- Number of carbon credits for 2022 = Footprint of 2021 - Carbon footprint of 2022

or

- Number of carbon credits for 2022 = Average of footprints from (2019, 20 and 21) - Average of estimated carbon footprints from (2022, 23, 24, 25, 26)

In case #1, the number of carbon credits reflects the actual and observed carbon performance of the farm. In the second case, the number of carbon credits reflects a projected anticipated reduction in carbon footprint over 5 years.

In general, this calculation method depends on each provider (it is important to have the standard used for the calculation clearly explained).

Similarly, depending on the model, the reference is calculated at the plot level (Verra VCS) or on a regional average (LBC).

Depending on the farm's starting point (for example already in ACS during the reference years), it may be more advantageous to choose one provider or another, to turn the calculation method to one's advantage.

How is a carbon footprint calculated?

Carbon footprint calculation methods for field crops revolve around three components of a farm's activity :

- Management of fertilization.

- Fuel consumption related to interventions on field crop plots.

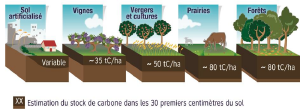

- Evolution of soil carbon stock.

Some programs propose to estimate exclusively the greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) directly inherent to agricultural practices (points 1 and 2 above) or conversely only the soil carbon stock (point 3). The amount of data to be entered can therefore vary but the result then does not take into account the entire carbon potential of the farm.

In some programs, soil tillage or other cultural practices can be taken into account. It is important to understand well how each provider calculates the credit and what is included or not in this calculation.

Different evaluation methods of greenhouse gas emissions and soil carbon storage exist and present varying levels of accuracy.

- Low Carbon Label (France only), which is based on the AMG model[2]

- ISO 14064-2 which uses the Cool Farm Tool model[3] and IPCC

- Verra-VCS, which uses the RothC model[4] and IPCC

Each model is a numerical method allowing to model the quantity of organic carbon in soils and the evolution of carbon storage over time.

Depending on the chosen methodology, the data to be entered are more or less complex and the results more or less precise and complete. It is important to remember that regardless of the model, results will be biased and inaccurate if the input data are incorrect or incomplete[5].

The Low Carbon Label?

The Low Carbon Label (LBC) is the national certification framework. The LBC is a French public initiative from the Ministry of Ecological Transition. Created in 2019, its objective is "to contribute to France's greenhouse gas emission reduction targets by 2050"[6]. The LBC offers several calculation methodologies, some proposed by private companies. For example, the SOBAC’ECO-TMM Method which measures greenhouse gas emission reductions linked to reduced input purchases.

The LBC Field Crops Method allows the valuation of GHG emission reductions and increased soil carbon storage.

International standards

Standards such as Verra VCS, Gold Standard, etc., allow qualifying and then selling carbon credits on the international market, resulting in a more dynamic selling price (higher volume).

Private certification frameworks

There are also private certification frameworks, such as those from Rize ag, Soilcapital, ERS - Ecosystem Restoration Standard, Riverse, or Inuk. The scientific legitimacy of these models relies on third-party validations: certification by external auditors, scientific committees, ISO standards, public consultations, etc.

Private company initiatives often try to address issues not covered by national or historical frameworks: taking into account new technologies (e.g., Artificial Intelligence or satellite imagery), simplifying data entry, better alignment with field and technical issues, etc.

What happens to these carbon certificates?

Once generated, carbon certificates are purchased by private organizations on the voluntary carbon market.

The voluntary carbon market

Legislation sets emission limits for GHG emissions for certain companies from high carbon impact sectors (electricity production, steel, paper, etc.), allocating them a certain quota of GHG emissions they cannot exceed. Sometimes called "pollution rights," these quotas are bought and sold on a market functioning similarly to a stock exchange. This is the so-called ETS market, for Emission Trading System[7], also called the mandatory carbon market. Companies subject to this carbon market must surrender at the end of the year as many quotas as tons of CO2 equivalent emitted into the atmosphere.

Beyond these regulatory obligations, some committed companies (whether or not subject to quotas) wish to fully participate in the planetary neutrality effort by financially supporting concrete emission reduction or carbon sequestration projects, for example from French agriculture. It is therefore voluntarily that these companies or organizations purchase carbon credits. These are traded between two parties over-the-counter, on the so-called voluntary carbon market. On the voluntary market, carbon credits are sold and bought through tailored transactions or contracts. The carbon credit price is set by the stakeholders themselves : it results from negotiation between the seller, the buyer, and any potential transaction mediators.

In short, carbon quotas are a maximum amount of CO2 equivalent emissions a company is authorized to emit while carbon credits represent carbon savings resulting from changes in practices between two scenarios. In both cases, it is the same unit (ton of CO2 equivalent), but they are distinct concepts. The mandatory and voluntary carbon markets are complementary but independent.

Why do companies buy carbon credits?

Companies' and organizations' motivations can be very diverse. It is systematically a strong commitment, generally driven by internal teams, expressed by the desire to contribute to agroecological transition. In this perspective, what better than to get in direct contact with the main stakeholders, namely the farmers.

Naturally, most companies also wish to communicate about this support (note that this is not the case for all), not only to associate their image with the supported projects but especially to raise awareness among their employees and partners about agricultural issues.

Many companies also anticipate future demands from European Union regulations regarding offsetting their carbon footprint by purchasing carbon credits. The voluntary market would then become connected with the mandatory market (this is not yet the case today). They thus seek to build expertise on carbon credits by participating in the voluntary market, investing in projects that inspire them.

Beyond an exclusively carbon vision, these companies wish to support local agricultural projects, in a logic of maintaining and developing the economic and ecological dynamism of territories. Through this financial contribution, funders aim to :

- Strengthen food resilience in the medium term thanks to soil health.

- Maintain soil fertility.

- Resilience to climate hazards.

- Preserve ecosystems.

- Reduce dependence on mineral and fossil inputs.

Finally, these companies are particularly interested in supporting projects whose broad impact is established : climate impact, biodiversity impact, but also social impact (maintaining employment in rural areas, farmers' working conditions, etc.).

What agronomic levers have the greatest impact on the farm's carbon footprint?

Agriculture, like any life science, unfortunately does not present a "miracle lever" for carbon capture. It is necessary to implement a set of levers to reduce the carbon balance at the farm scale after adopting or evolving practices. That said, some levers generally have a significant impact.

The most important levers[8] taken into account are :

- Additions of intermediate cover crops.

- Reduction of soil tillage to avoid disturbance.

- Additions of legumes in the crop rotation.

- Optimization of mineral and organic fertilization.

- Increase in yields.

- Retention of crop residues on plots.

Is increasing yields a lever?

Indeed, a high yield is synonymous with a crop with a large biomass : increasing yields also means increasing biomass, and thus crop residues which, left on the plot, will provide organic matter to the soil.

It is nevertheless important to note that if the yield increase is linked to an increase in mineral fertilizer use, it is possible that the overall carbon balance of the farm is negatively impacted : the beneficial effect of crop residues would then be offset by the carbon footprint of mineral fertilizers.

How much can be earned with carbon credits?

Depending on the changes in practices (more or less significant), a farm can aim for 0.5 to 3 carbon credits per hectare per year ("cc/ha"). They are sold at a market unit price between €25 and €50[5] depending on the programs (in 2024).

An important point that will make a difference from one provider to another is the program duration:

- LBC: 5 years

- Cargill: 3 years (renewable)

- Verra VSC: 10 years

Each year, there is an evaluation of cultural practices to reassess the farm's sequestration capacity and emission reductions compared to the reference years.

Example : I can generate 1 cc/ha by evolving some of my practices. My farm is 100 ha. I can earn : 1 x 100 x €35 = €3500 per year.

This allows a quick assessment of the interest of these financing schemes for the farm before committing to a carbon program.

Are carbon credits cumulative with other aids?

Carbon credits are by nature a carbon offset, not a direct aid from a public body. Carbon certificates can therefore be combined with Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) aids in particular.

However, it is not possible to declare the same low-carbon project in several programs from different companies. Indeed, by their nature, carbon credits (which represent a carbon saving) can only be accounted for and sold once.

To avoid double counting, several actors have federated by creating the Climate Agriculture Alliance (CAA), an association whose mission is to facilitate carbon valorization in agriculture. Thanks to its FarmVault registry, it guarantees the traceability of emission reductions and carbon capture by farms participating in carbon payment programs.

How much does it cost to generate carbon credits?

To generate a carbon credit, a farm needs :

- To choose the practices it wishes to evolve.

- To calculate its project carbon footprint.

- To enter a carbon program under the framework of its choice.

- To sell the carbon credits.

Some providers offer support on one or more of these steps, with different billing models. These prices vary depending on the model deployed by the companies.

Isn't it better to wait for the carbon price to increase before entering a program?

If the carbon price trend is upward on the voluntary market, it is nevertheless good to remember that :

- Soil capacity restoration takes time, delaying the start of practice changes also delays their beneficial effects.

- When postponing entry into a carbon program by one year, one loses all the carbon credits that could have been generated that year by initiating changes.

The important thing is mainly to consider these credits as a way to remunerate part of the effort that would have been implemented anyway - and thus to benefit from it as early as possible.

Example : Farm A enters a carbon program in 2023. The carbon price is set at €35 per ton. It generates 100 CC in 2023. It can thus earn €3500 the first year. In 2024, it generates 120 CC. It can thus obtain €4200, i.e., 3500 + 4200 = €7700 of gains at the end of 2024.

Farm B waits for the carbon price to increase. It enters a carbon program in 2024. The carbon price has increased by 15% to reach €40/T. It generates 100 CC for its first year. This represents €4000 of gains at the end of 2024.

- ↑ Pellerin et al., 2019

- ↑ AMG Model: http://www.agro-transfert-rt.org/projets/consortium-amg/

- ↑ Cool Farm Tool Model: https://coolfarm.org/

- ↑ RothC Model: https://www.rothamsted.ac.uk/rothamsted-carbon-model-rothc

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Document comparing existing standards: https://www.ecologie.gouv.fr/sites/default/files/documents/Santards-compensation_MTE.pdf

- ↑ https://www.ecologie.gouv.fr/label-bas-carbone

- ↑ https://www.ecologie.gouv.fr/marches-du-carbone

- ↑ See the INRAe 4per1000 report: https://www.inrae.fr/actualites/stocker-4-1-000-carbone-sols-potentiel-france

La version initiale de cet article a été rédigée par Alexandre Benoist, Etienne Variot, Elise Leflour et Nicolas Dubois.