Biological control

While biological control under shelters sees the emergence of effective and varied solutions, biological control in open fields is less straightforward. It is considered more globally within a strategy of restructuring an agricultural landscape that promotes auxiliaries. It is about finding the right balance between uncultivated and cultivated space that restores ecosystem functions and provides indirect services to production, including better natural regulation by the auxiliaries. Thus, combined with practices adapted to soil and climate, a landscape providing habitats and food resources to auxiliaries allows for optimal functioning at the plot level.

Functional biodiversity serving my crops

Principles of biological regulation

Biological control is based on a simple principle: using a biological agent to fight against one or more pests of crops. Depending on the insect life cycle, the relationships can be predation or parasitism. Simplified, there are two main forms of biological control:

- Invasive biological control: an auxiliary is introduced into the environment to regulate a specific pest. Effective in confined environments such as greenhouses, it is much less so outdoors despite great successes like the trichogramma against the corn borer.

- Biological control by habitat conservation (BCHC), which this article addresses, consists of creating a landscape environment favorable to a suite of crop auxiliaries. Hedges, embankments, and other grassy strips are active landscape elements called "ecological infrastructure". For more than ten years, research has highlighted the success factors of this approach for farmers.

Cultivating useful biodiversity is, in a sense, "breeding" auxiliary insects, that is, providing them shelter and food.

To simplify, auxiliaries of crops can be divided into two categories: floricolous and predators. The first are mainly flying insects at the adult stage feeding on pollen and nectar. Among the best known are hoverflies, ladybugs, lacewings, and hymenopteran parasitoids. The second need prey quite early in the season to be active and are mostly soil arthropods: ground beetles and rove beetles.

From field to landscape approach: landscape engineering within farmers' reach

Natural pest regulation is a process involving various spatial scales, which makes this approach complex and sometimes costly. The establishment of ecological infrastructure is considered at the landscape or parcel group scale to increase the chances of success of measures at the cultivated field scale. Auxiliaries have life cycles that extend beyond the simple plot and have differentiated needs in terms of habitats and nutritional resources between adult and larval stages and during activity and rest periods.

Several factors are recognized as having a significant impact on insect populations:

- Density of natural uncultivated habitats, i.e., the proportion occupied by hedges, embankments, ditches, grassy and flowered strips within a territory. It is estimated that an agricultural landscape should consist of 20% fixed elements to allow good migration of auxiliary populations. Sometimes established in bocage areas, this objective is difficult to consider in cereal plains.

- Diversity and composition of habitats and notably their capacity to provide pollen and nectar resources and a wide range of varied ecological niches (dead wood, undergrowth…). Thus, hedges will start flowering early and finish as late as possible to maintain intense activity of floricolous auxiliaries.

- Connectivity of different habitats to each other, playing a key role in the migration of species most sensitive to cultivated soils.

Concrete action levers for the farmer

Two simple landscape elements can be considered that can be easily implemented at field edges: the hedge and grassy or flowered strips. Existing wooded strips and small woods are also functional ecological infrastructures.

A functional hedge consists of several layers: herbaceous, shrubby, and arboreal. An average single-row hedge is generally 3m wide and is composed of species with successive flowering over 5 to 6 months from early spring to autumn (Fig. 1). This continuous flow of nectar and pollen is essential for the proliferation and maintenance of floricolous auxiliary populations. The diversity of habitats at the base of the hedge and within the different layers creates a favorable environment for many arthropod species, providing a wide choice of prey and hosts for predatory and parasitic auxiliaries early in the season.

Fig. 1: Generic composition of a functional hedge allowing the flower cascade phenomenon:

- Blackthorn: March and April

- Hawthorn: May

- Wild rose: June and July

- Honeysuckle: June and July

- Bramble: August

- Ivy: September and October

A flowered strip provides a very effective complementary source of pollen and nectar to the hedge and can be an interesting substitute. From 3 to sometimes 10 m, flowered strips are both a habitat preserved from disturbances and a source of pollen. Good composition and appropriate management are the keys to success. They require diversified floral composition to extend the flowering period as much as possible by favoring successive bloomings. Different floral architectures are also sought, with open corolla flowers to favor dipterans and micro-hymenopterans (mainly Apiaceae, Asteraceae, Hydrophyllaceae families: wild carrot, chamomile, daisy, yarrow, common ammi, mallow, St. John's wort, cornflower, phacelia) and deep ones (legumes, for floricolous hymenopterans: bird's-foot trefoil, melilot, sainfoin, various clover species…). Late mowing is essential to allow auxiliaries to benefit from late summer flowering.

From theory to practice: strategies for the farmer

How to proceed concretely? First, it is necessary to set the framework by taking stock of the landscape functionality on the farm. Heterogeneous or particular zones can be identified, more or less favorable to establishing a biological balance.

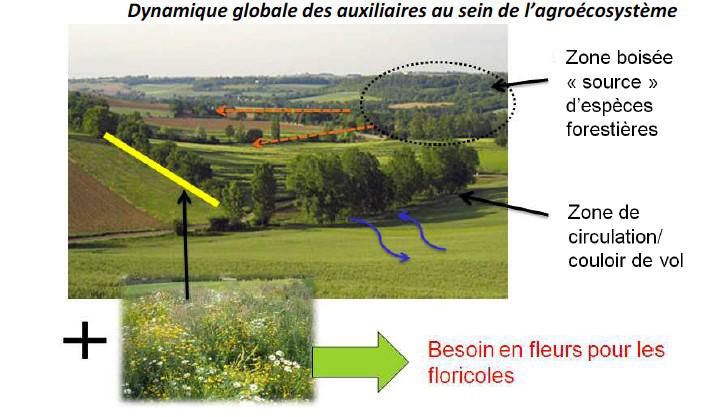

There are "source" spaces of auxiliaries, typically areas bearing functional landscape elements for several decades, a forest or a small wood, and "sink" spaces that will benefit from the migration of auxiliaries from these more favorable areas. Cultivated fields and newly established infrastructures will be gradually colonized. The farmer, alone or with the help of a technician, can then determine the "source" areas of the farm and develop his plots from these.

A favorable initial landscape is composed of a more or less dense network of various hedges, accompanied or not by grassy strips bordering fields of less than 5 hectares. These hedges must be connected to each other. It has been shown that a two-year-old hedge connected to several old hedges supports a greater diversity and density of ground beetles than a thirty-year-old single hedge separating two fields and not linked to an old network (experiment conducted in Charente-Maritime from 2007 to 2012).

A typical unfavorable environment is very open and has few or no landscape elements. These are typical landscapes of the large cereal plains of northern France, characterized by plots larger than 30 ha scattered with a few groves.

Generally, on a parcel system, more or less heterogeneous zones are found. These zones will be treated differently:

In an environment favorable to useful biodiversity, the approach will be maintenance, good management, and optimization by implementing 3m flowered strips with late summer mowing and hedge maintenance.

In the second, many limitations exist; achieving a satisfactory result can take several years or may never be reached if neighboring fields do not follow the same dynamic. The minimal resource threshold is insufficient and the distance from "source" areas too great. In the case of isolated plots, this will probably never be possible.

In this case, two strategies exist: if a grove or hedge borders one end of the parcel group, the development will systematically be connected there. A trapping of Carabidae and/or Syrphidae can be carried out by a competent person to verify if these areas really constitute "source" zones of auxiliaries.

In the case of an isolated and bare plot, the establishment of a flowered strip to attract flying auxiliary insects, the only ones able to cover long distances, is essential. Beyond 300m distance between two landscape elements, migration chances are low, and the effectiveness of the development is questioned. Thus, it is always advisable to choose implantation zones close to a source area.

Summary

A well-thought-out functional landscape development strategy thus takes into account the scales of the landscape and the field, considering the specifics of the parcel system. "Source" and "sink" spaces must be defined, and the implantation of developments linked to the "source" areas of auxiliaries. The implantation of functional hedges requires respecting certain rules including a specific composition allowing early and late flowering; annexing a flowered strip is necessary to optimize the whole and must be positioned to favor the circulation of floricolous insects.

Sources and author

La version initiale de cet article a été rédigée par Sébastien Roumegous.