Ploughing is an agricultural technique that consists of turning over the top layer of soil using a plough. This operation traditionally aims to bury crop residues, control weeds, loosen the soil, and prepare the seedbed. Ploughing can be performed at different depths, depending on the farmer's objectives and the nature of the soil.

Agroecology aims to reconcile agricultural production with respect for the ecosystem. In this perspective, traditional ploughing is increasingly questioned in favor of alternative practices that preserve soil health.

Objectives of ploughing

Soil loosening

Ploughing allows loosening the soil by turning the earth up to 30 cm deep, which breaks the surface crust and aerates the soil. Ploughing thus facilitates crop rooting and improves water and air circulation[1].

The loosened soil after ploughing facilitates crop emergence. However, this advantage is only valid in the short term.

Weed reduction

Turning over the soil limits competition for young plants. Ploughing allows burying seeds and weeds found on the surface between 20 and 30 cm deep. At this depth, seeds cannot germinate. Ploughing thus eliminates weeds without using herbicides.

To ensure good weed control, it is necessary to properly adjust the plough:

- First, before hitching the plough, make sure the tractor tires are properly inflated as well as the length and position of the skimmers : the length must be identical on the left and right, and a rear position on the lift arm ensures better lifting performance.

- For the plough, it is better to use helical mouldboards because they allow better turning by accompanying the soil flow longer.

- The height of the skimmers must also be well chosen to optimize turning. This height must be equal to the ploughing depth. If the skimmer is too high, burial will be less effective; if it is too low, turning will not be properly done.

- The position of the skimmer supports must also be chosen according to objectives: an advanced position for better burial and a rear position to avoid clogging with plant debris[2].

Rapid incorporation of amendments and plant residues

Ploughing allows mixing and burying amendments. Fertilizers and composts are thus better distributed in the soil profile. It also accelerates the decomposition of plant residues and enriches the soil in organic matter in the short term[1].

Pest and disease management

Ploughing disrupts the cycle of certain harmful organisms by modifying soil properties, in the same way it impacts beneficial microorganisms for crops.

Disadvantages of ploughing

Erosion and soil loss

Bare soil is more vulnerable to erosion by wind and water. Moreover, when ploughing along the slope, aggregates and soil clods move downhill, causing soil loss at the top of the plot. This soil loss is problematic for long-term fertility because soil formation is a slow process. Soils lose on average 1.5 tons of earth per hectare per year in France while only about one ton per hectare per year is formed. Depending on the region, the difference is sometimes even more marked: in Europe, the average soil erosion rate is 17t/ha/year[3][4].

Decrease in soil life

Turning over disturbs soil organisms. Indeed, ploughing modifies the soil structure but also the distribution of organic matter and nutrients, temperature, and moisture.

For example, earthworms are impacted by the mechanical action itself, by the turning of the earth which can cause desiccation, and also by greater exposure to predators.

Fungi are also disturbed because their mycelium is damaged by the mechanical action of ploughing, and macroaggregates which represent their physical habitat in the soil are destroyed[5].

Decrease in soil fertility

Ploughing causes a decrease in the rate of organic matter in soils. By turning the earth, organic matter is exposed to oxygen which leads to its rapid mineralization. In the short term, this provides many nutrients for crops but in the long term, organic matter is not renewed and soil fertility decreases[6].

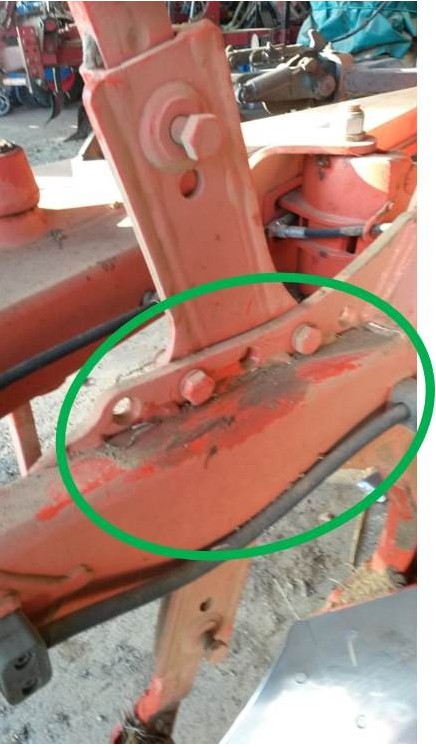

Degradation of soil structure

In the long term, repeated ploughing can cause the formation of a plough pan. This is a compact layer a few centimeters thick located at the base of the ploughed zone, under the share's passage. This layer limits the passage of water and air. Thus, below the plough pan, anoxic conditions form, and above it, the soil can become waterlogged because water no longer drains deeply. Furthermore, roots have difficulty crossing this layer, limiting crop development[7].

To break this plough pan, it is possible to perform subsoiling or deep ripping depending on the depth of the plough pan: beyond 50 cm depth, subsoiling is appropriate. It is recommended to check with a spade during the tool's passage that it reaches the compacted zones to be worked[8].

To avoid the formation of a plough pan, it is preferable to limit soil work, establish cover crops with deep root systems, and if soil work is necessary, avoid frequent passage of heavy machinery and work on well-drained soil.

Energy dependence

Labour requires significant fuel consumption.

Alternative practices

Reduced tillage techniques

Simplified cropping techniques such as no-till or strip-till limit soil turnover while preparing the seedbed. Soil work may sometimes be necessary but ploughing is not necessarily required; these techniques thus offer a compromise. Strip-till works only the seed row, and no-till consists of sowing without any soil work.

Cover crops

Establishing covers between main crops protects the soil, limits erosion, and enriches the soil in organic matter. Indeed, cover crop roots improve soil porosity. Moreover, the cover prevents leaving the soil bare during the intercrop period. This both protects the soil from wind erosion and combats erosion related to runoff because covers improve water infiltration into the soil[9].

Diversify and lengthen crop rotation

The diversity of root systems allows structuring the soil by promoting its porosity and limiting compaction. Thus, in a no-till system, it is necessary to have a longer and more diversified rotation to promote better soil structure.

Agroforestry and hedges

In Agroforestry, trees and hedges form a mechanical barrier against wind and rain, which helps limit erosion, and their deep root systems help structure the soil.

Implementation

- Assess the need for ploughing: adapt the frequency and depth of ploughing according to soil type, climate, and crops.

- Prefer soil work at the right time: work soil that is neither too dry nor too wet to limit compaction.

- Do not work the soil too deeply: ploughing should be as shallow as possible to avoid mixing aerobic and anaerobic soil layers. Indeed, this mixing causes organic matter fermentation instead of mineralization. This limits the soil's natural fertility.

- Gradually introduce alternatives: test simplified cropping techniques, no-till, or cover crops on part of the farm to see if it is possible to favor these solutions.

- Observe soil life: a living soil (presence of earthworms, crumbly structure) is an indicator of suitable practices.

- Adjust ploughing speed: on average, the recommended speed is 4 to 8 km/h. This speed varies depending on soil type and the objective. Too high a speed prevents deep burial of all weed seeds[2].

When to plough?

If ploughing is essential, it is important to choose the ploughing period carefully to avoid weakening the soil.

- In clay soils, it is preferable to plough early in the season, on well-drained but not completely dry soil.

- In sandy or crusting soils, it is advised to plough later in the season to avoid precipitation reducing the porosity created by ploughing or compacting the freshly loosened soil. This prevents the formation of a crust.

It is better not to plough every year. Alternating plough/no-plough avoids bringing to the surface weed seeds buried the previous year.

Moreover, it is not recommended to plough when there is a risk of frost. Indeed, ploughing promotes water evaporation by aerating the soil. This evaporation increases humidity, which increases losses. For example, in viticulture, a 25% increase in humidity causes a 50% additional bud loss in the case of a spring frost[10].

Appendices

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 https://www.inrae.fr/actualites/agriculture-conservation-se-passer-labour-pas-si-facile

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 https://www.arvalis.fr/infos-techniques/bien-regler-sa-charrue#:~:text=Il%20convient%20plut%C3%B4t%20de%20viser,profondeur%20de%2020%20cm%20minimum

- ↑ https://www.supagro.fr/ress-pepites/ingenierieprobleme/co/2_3_DegradationSol.html

- ↑ https://www.statistiques.developpement-durable.gouv.fr/les-sols-en-france-synthese-des-connaissances-en-2022

- ↑ https://nature-et-savoirs.adwed.fr/bdd/les-enjeux/les-enjeux-de-la-nature/etude-d-impact-du-sol-cultures.pdf

- ↑ https://agricultureduvivant.org/lagroecologie/limiter-le-travail-du-sol-des-techniques-simplifiees-au-non-ploughing/

- ↑ https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Semelle_de_labour#:~:text=La%20semelle%20de%20labour%20est,passage%20du%20soc%20de%20charrue

- ↑ https://www.perspectives-agricoles.com/sites/default/files/imported_files/397_284578109318259179.pdf

- ↑ https://agriculture-de-conservation.com/sites/agriculture-de-conservation.com/IMG/pdf/non_labour_TSL_zanella.pdf

- ↑ https://www.vitisphere.com/actualite-98525--pas-de-travail-du-sol-dans-les-vignes-avant-un-gel-sinon-bonjour-les-degats-.html